Now Reading: 57 ways to capture a dying star: Astronomers get a glimpse of what will happen when our sun dies

-

01

57 ways to capture a dying star: Astronomers get a glimpse of what will happen when our sun dies

57 ways to capture a dying star: Astronomers get a glimpse of what will happen when our sun dies

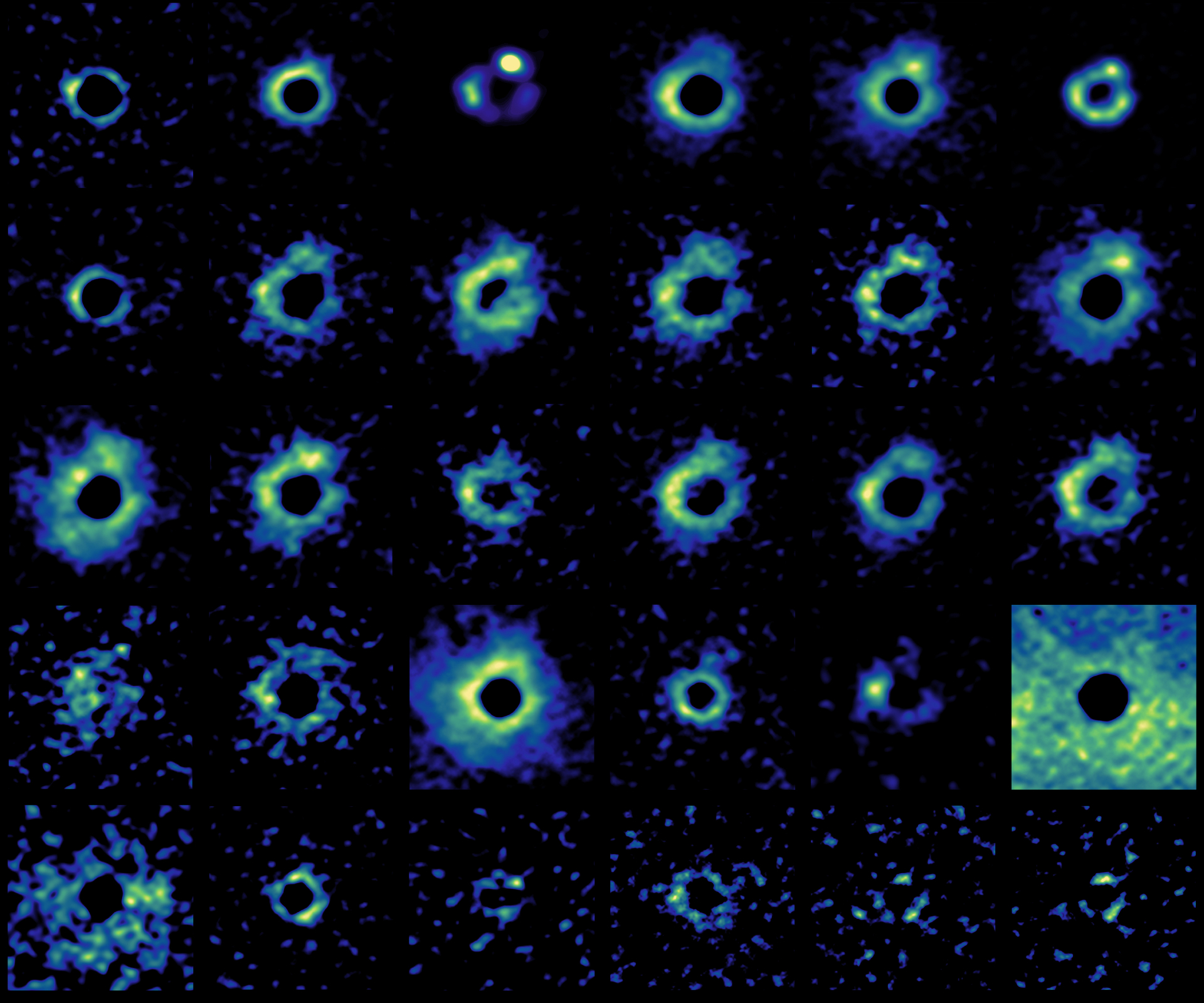

Astronomers have observed 57 different “faces” of a distant exploding star using different molecules to capture a varying picture of stellar death and its impact on its environment. The research could give us a more complete prediction of what will happen to the sun in around 5 billion years when it begins its own death throes and swells out as a red giant star, consuming its inner planets, including Earth.

The observations were made using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a collection of 66 radio antennas in northern Chile that come together to comprise the largest astronomical project in existence.

“With ALMA, we can now see the atmosphere of a dying star with a level of clarity in a similar way to what we do for the sun, but through dozens of different molecular views,” team leader Keiichi Ohnaka, from Universidad Andres Bello (Chile), said in a statement. “Each molecule reveals a different face of W Hydrae, revealing a surprisingly dynamic and complex environment.

“The combination of ALMA and VLT/SPHERE data lets us connect gas motions, molecular chemistry, and dust formation almost in real time — something that has been difficult until now.”

Different molecules tell a different story about dying stars

It is the exceptional sensitivity of ALMA, which is capable of capturing the equivalent of snapping a picture of a grain of rice at a distance of 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) away, that allowed the team to see shifting structures within the red giant and its atmosphere. These included “clumps, arcs and plumes,” all of which varied depending on the molecule studied. The different molecules offer unique views of W Hydrae because the spectral lines seen by ALMA, the optical “fingerprints” of different chemicals, form under different conditions.

When viewed in these different spectral lines, the red giant was swollen out to many times its original size. In fact, were it placed where the sun sits in the solar system, its outer layers would engulf the planets all the way out to the orbit of Mars. These expanded regions appear as clouds that are sculpted by shocks, pulsations and the transfer of heat from the central star.

The ALMA observations showed a variation in the motion of gas around W Hydrae, with gas closer to the heart of the red giant barreling outwards at speeds of around 22,400 miles per hour (36,000 km/h), while gas in higher layers is falling inward with a speed of around 29,000 miles per hour (46,000 km/h). This creates a constantly shifting layered flow pattern, which matches 3D modelling of how convective cells and pulsation-driven shocks shape the atmosphere of red giants.

One of the most remarkable elements of the team’s findings was the revelation of the observed molecules and newborn dust, which emerged when ALMA findings were compared with data collected by VLT’s SPHERE instrument. The fact that the two sets of observations were made with just nine days between them allowed the team to link gas chemistry to dust formation in real time. The team found that molecules such as silicon monoxide, water vapor, and aluminum monoxide appear exactly where clumpy dust clouds were seen in the VLT data. That indicates that these chemicals are directly involved in the formation of dust grains.

They also found that other molecules, such as sulfur monoxide, sulfur dioxide, titanium oxide, and possibly titanium dioxide, overlap with dust in some regions around W Hydrae and may therefore contribute to dust formation through shock-driven chemistry. On the other hand, molecules like hydrogen cyanide were found to form close to the star but don’t appear to directly participate in dust formation.

As dying stars like W Hydrae shed their outer layers, they enrich their cosmic surroundings, or the interstellar medium, with molecules that become the building blocks of new stars and planets. This research and the observations of dust formation and outflows from a red giant could help better understand how AGB stars lose mass, one of the longest-standing unresolved problems in stellar astrophysics.

“Mass loss in AGB stars is one of the biggest unsolved challenges in stellar astrophysics,” team member Ka Tat Wong, from Uppsala University, said. “With ALMA, we can now directly observe the regions where this outflow begins, where shocks, chemistry, and dust formation all interact. W Hydrae gives us a rare opportunity to test and refine our models with real, spatially resolved data.”

W Hydrae may also act as a scientific crystal ball, providing a preview of the sun’s fate and how our star will enrich our cosmic backyard with the stuff needed for new stars, planets, and even life itself.

The team’s research was published on Dec. 2 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

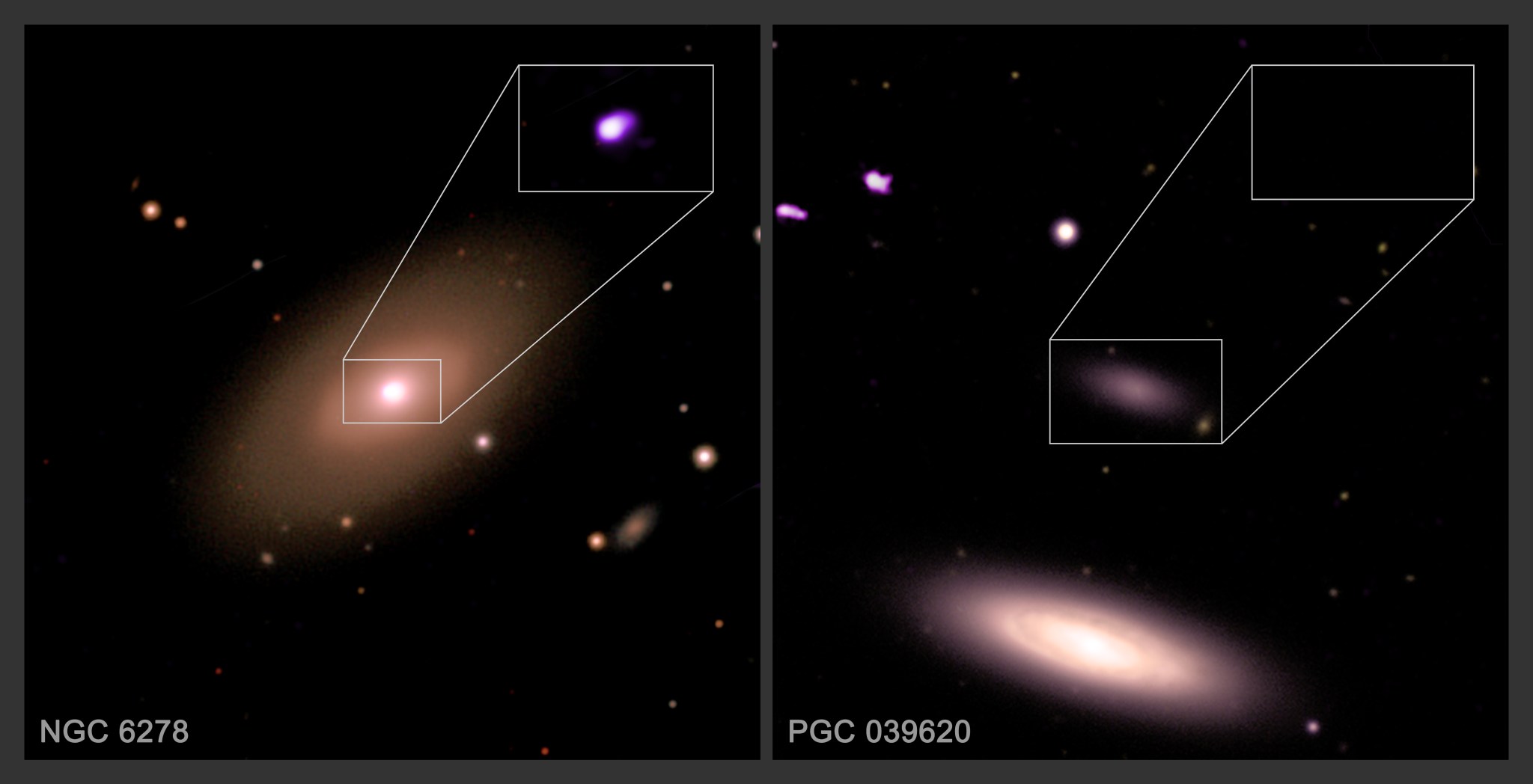

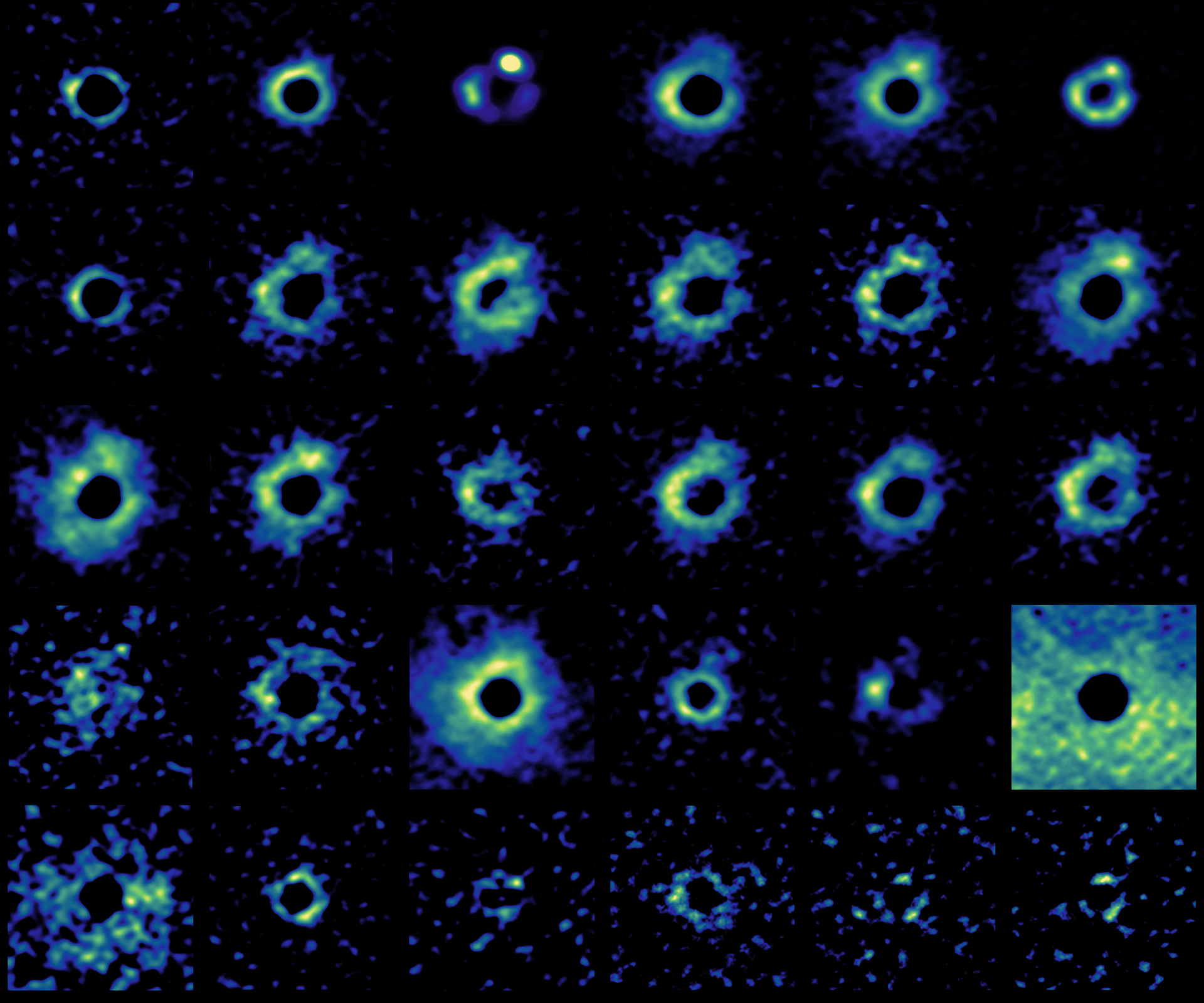

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

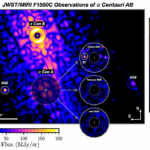

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits