At the American Meteorological Society’s annual meeting in Baltimore, frustration with government data purchases rose to the surface.

“In the private sector, it’s easy for us to sign a three-year deal or a five-year deal,” Michael Eilts, Spire Global general manager of weather and Earth intelligence, said Jan. 30 during an AMS panel on public-private partnerships. “Working with the government, our typical contract right now is six months.”

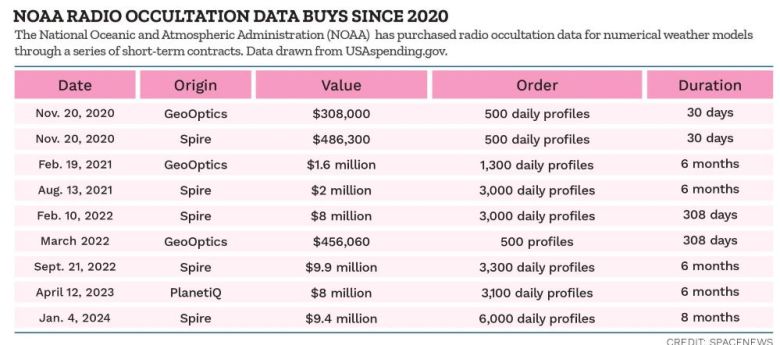

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has purchased radio occultation data through a series of short-term contracts. It’s part of the Commercial Data Purchase program, an initiative designed to improve NOAA forecasts and bolster the commercial market for space-based weather data.

Winners of the NOAA contracts were GeoOptics in February 2021, Spire in August 2021, Spire in February 2022 and PlanetIQ in April 2023. Spire also won a $9.4 million, eight-month contract on Jan. 4 to supply radio occultation data to feed numerical weather prediction models.

The short-term contracts make it “almost impossible” for Spire to continually invest in its 80-cubesat constellation in addition to developing new applications like soil moisture and sea ice measurements, Eilts said.

“Imagine talking to an investor and saying, ‘We got $9 million this quarter. We got nothing the next quarter. Then, we got $3 million the next quarter.’ It just doesn’t work,” Eilts said. “We need long-term commitments from government sources, just like we get long-term commitments from private companies.”

Predictable revenue

People at AMS were not surprised by Eilts’ sentiments. Similar views are often expressed by entrepreneurs investing millions in small satellites and sensors to fulfill government demand for imagery and data.

What was surprising was revealing those views in a public forum. Most people express frustration with commercial data programs established by NOAA, NASA and other government agencies in private conversations.

For example, an industry executive who asked not to be identified said, “The structure of the NOAA data purchases has hamstrung commercial investment in not just radio occultation but also other satellite weather observations. Industry has been clear in request for information responses dating back almost a decade that the single most important requirement for a successful program (more than price, license terms or any other issue) was long-term contracts with predictable revenue. NOAA has ignored this feedback and as a result is now suffering from high prices for limited amounts of data.”

Best value

Rather than ignoring the feedback, a NOAA leader underscored another priority.

“The primary consideration of the Government for the period of performance is obtaining the best value,” Stephen Volz, assistant administrator for NOAA’s Satellite and Information Service, said by email.

The people overseeing the Commercial Data Program finalize each year’s data procurement plan when they know how much funding Congress has budgeted. Delivery orders are then awarded “based on the number of profiles that can be procured with the funding received, and the need for data within NOAA,” Volz said. “Six months has been our base period of performance to date.”

NOAA is “aware that the duration of contracts has consequences for vendors,” Volz added. “Longer contracts would have benefits as well as negative effects on vendors. Long-term contracts would be detrimental to companies seeking to enter the market, and a single vendor marketplace would likely emerge, leading to higher overall pricing. The Government does consider these issues in acquisition planning, but the primary concern is to obtain the best value for the Government given the funding allocated to the program.”

Paradigm shift

Frustration with the NOAA program is not new.

Congress gave NOAA $3 million in 2016 to establish the Commercial Weather Data Pilot to evaluate the utility of commercial observations. Four years later, after an extensive evaluation, NOAA concluded that the commercial sector could produce data of high enough quality to meet the needs of operational weather forecasts and announced plans to begin buying commercial data for operational use.

“When Congress allocated funds for commercial data purchases and evaluation, everybody got excited that it would change things quickly,” Dallas Masters, vice president at Muon Space, a Silicon Valley startup building smallsat constellations for remote sensing, said in an interview at the AMS conference. “But it is going more slowly than we expected.”

Masters added, “I don’t fault the agencies. It’s a paradigm shift that we’re all undergoing and sometimes paradigm shifts are hard to do quickly.”

Embracing commercial

NOAA obtains data from dozens of satellites owned and operated by the U.S. government, international partners, companies and nonprofits.

“We have to embrace and understand how we’re going to use new commercial capabilities, which may be duplicative or complementary to what we have, or completely orthogonal,” Volz said in an AMS talk on NOAA’s next-generation observing system. “How do we bring those in in a way that we benefit from those and not treat them as invasive species and try and get rid of them? We don’t fight them. We embrace them because they bring a capability that we can’t generate as quickly or even are funded to do in a particular way. But it’s still information value that we have to integrate.”

Mismatched decision cycles

NASA’s Earth Science Division has also encountered hurdles in its Commercial SmallSat Data Acquisition Program. Since the program started in 2017, Airbus U.S., Maxar Technologies, Planet, Spire, Teledyne Brown Engineering and the Polar Geospatial Center at the University of Minnesota have won contracts to share optical, hyperspectral, synthetic aperture radar and other datasets.

The space agency continues to look for “creative ways to partner with the private sector” from observations to “analytics” and “throughout the value chain,” Karen St. Germain, NASA’s Earth Science Division director, said during an AMS Town Hall meeting. “I will say it’s not as easy as it sounds.”

One issue is the pace of decision making. In a couple months, NASA leaders will begin considering the agency’s 2026 budget request.

“Our decision cycles are a lot longer than the private sector’s,” St. Germain said. “That’s what makes it a little bit tricky. But that doesn’t mean we aren’t looking at opportunities.”

A promising template

Government officials seeking to forge more durable relationships with industry might consider U.S. intelligence agency programs, two commercial weather data providers suggested.

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and National Reconnaissance Office have ongoing relationships with companies that supply imagery and data.

“I believe that if we can all put our heads together and think through it, we can build a long-term partnership,” Eilts said.

This article first appeared in the February 2024 issue of SpaceNews magazine.