Now Reading: Flight engineers give NASA’s Dragonfly lift

1

-

01

Flight engineers give NASA’s Dragonfly lift

Flight engineers give NASA’s Dragonfly lift

In sending a car-sized rotorcraft to explore Saturn’s moon Titan, NASA’s Dragonfly mission will undertake an unprecedented voyage of scientific discovery. And the work to ensure this first-of-its-kind project can fulfill its ambitious exploration vision is underway in some of the nation’s most advanced space simulation and testing laboratories.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

[mc4wp_form id=314]

Previous Post

Next Post

Loading Next Post...

Popular Now

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

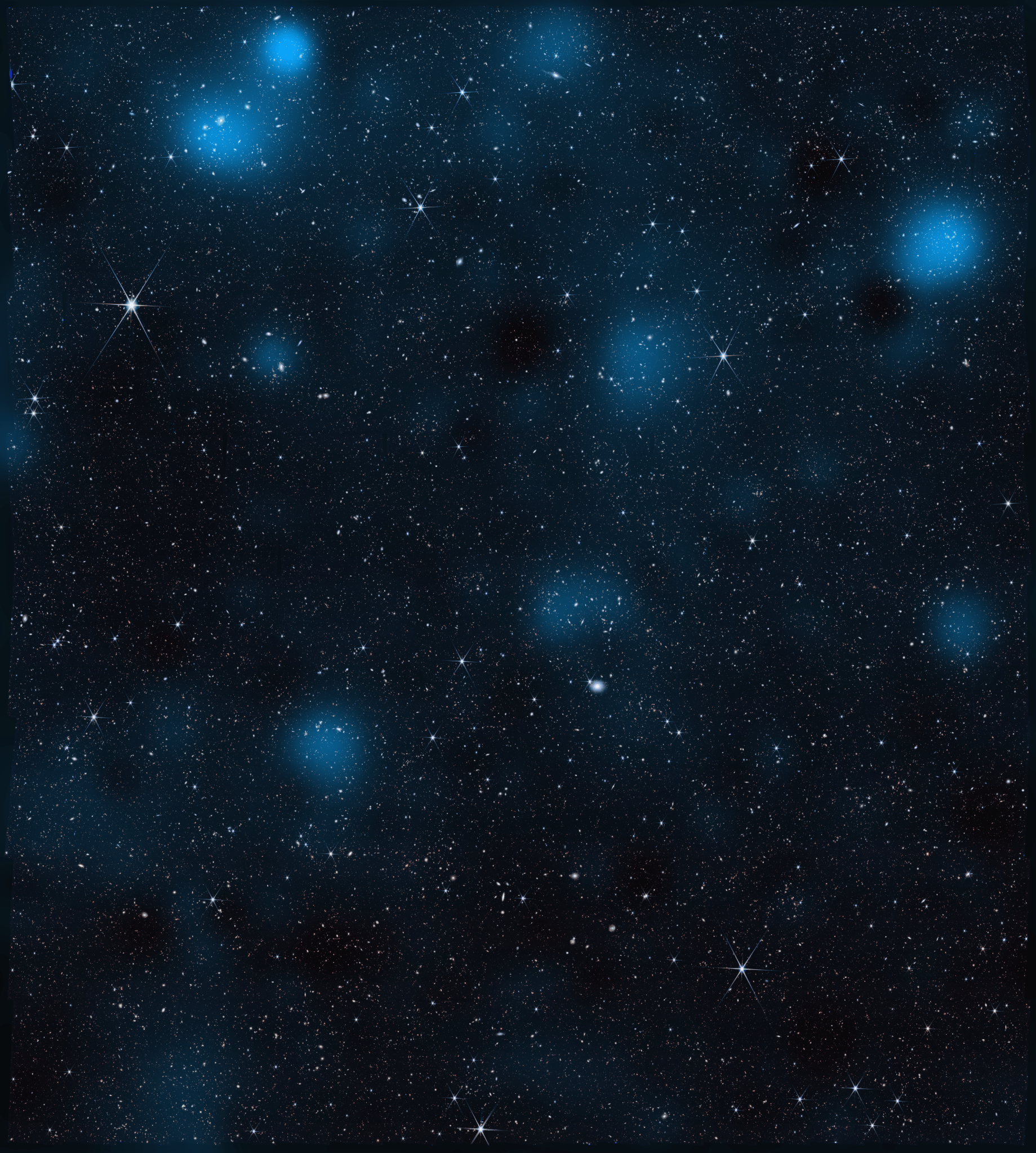

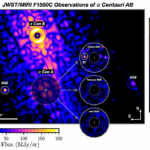

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

Scroll to Top