The moon could soon become humanity’s first extraterrestrial construction zone, with plans for permanent human settlements, a levitating train system and innovative new nuclear reactors tentatively in the works. But before any of that happens, the moon’s going to need light.

One day on the moon lasts the equivalent of two Earth weeks, and the freezing lunar nights are no shorter. These long, dark nights have already proved disastrous for lunar landers that rely on sunlight for power — and they could pose even greater threats to human explorers in the coming decades.

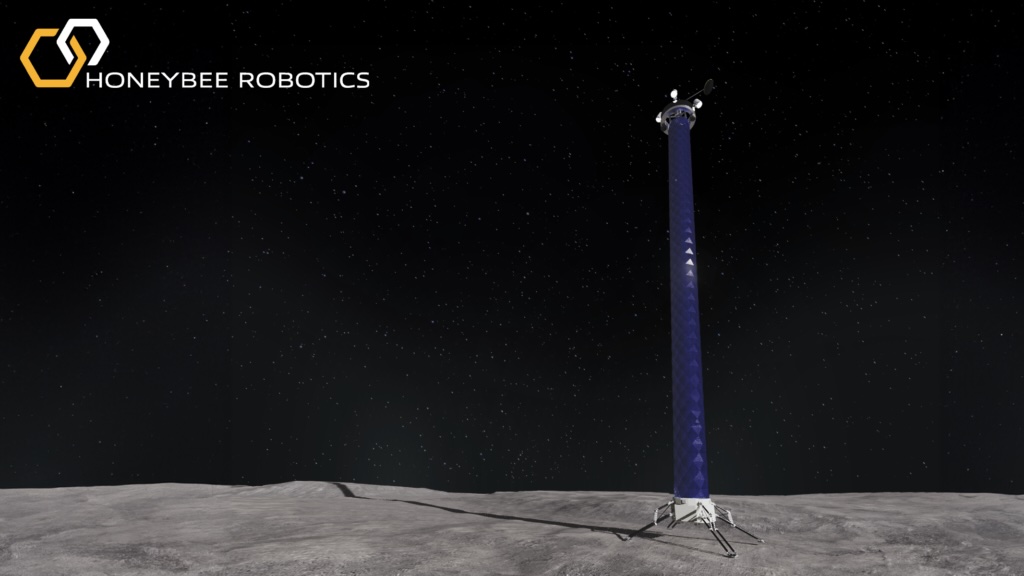

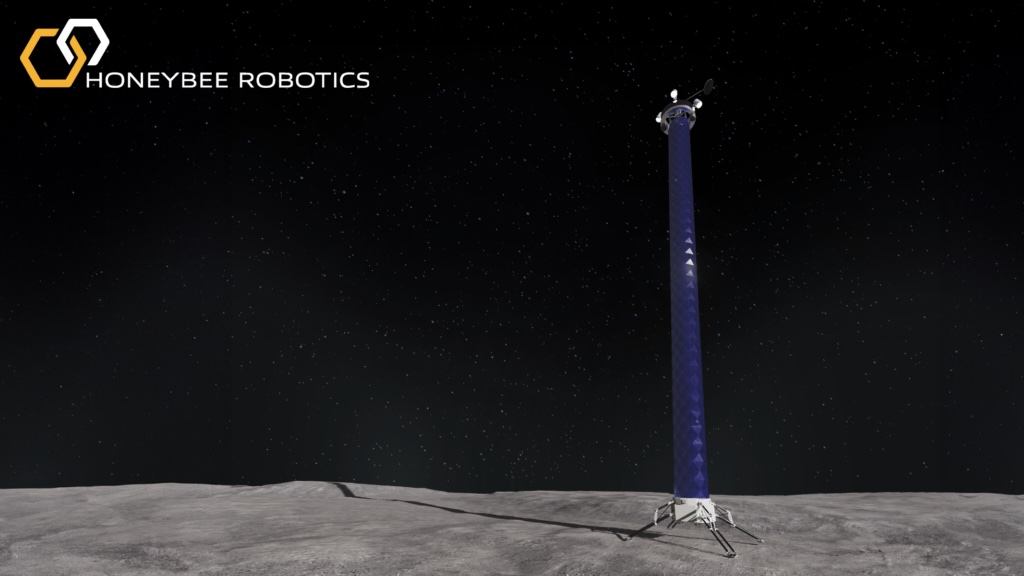

Now, the space technology company Honeybee Robotics (part of Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin) has proposed a solution: enormous lunar streetlamps that double as solar-powered batteries.

It may sound far-fetched, but the project — called the Lunar Utility Navigation with Advanced Remote Sensing and Autonomous Beaming for Energy Redistribution, or LUNARSABER — is one of several being funded by the U.S. government’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to jump-start the next era of lunar exploration. And a recent promotional video posted to YouTube shows that the tech is making strides.

As the project’s principal investigator, Vishnu Sanigepalli, explains in the video, each LUNARSABER lamp would be far taller than the ones standing on your street corner — in fact, at 330 feet (100 meters) tall, they’d be taller than the Statue of Liberty. These massive light poles are designed to store solar energy during the lunar daytime and then light up the surrounding area with powerful floodlights during the two-week lunar night that follows.

Related: Scientists map 1,000 feet of hidden ‘structures’ deep below the dark side of the moon

The lamps’ high altitude is crucial not only for peering over the rims of vast lunar craters, but also for elevating up to 0.9 tons (1 metric ton) of science equipment, such as cameras and communications devices, to higher vantage points, Sanigepalli explained.

Meanwhile, the base of each tower would be equipped with power adapters to help recharge lunar rovers or other hypothetical moon infrastructure that were nearby. If several LUNARSABER towers can be deployed to different parts of the lunar surface, this network of lighthouses could serve as the moon’s first power grid, Sanigepalli said.

Of course, erecting such colossal structures on the moon poses challenges. To address them, Honeybee engineers have designed an automated system by which each LUNARSABER tower could effectively rise out of its own base, by bending rolled-up bands of metal into towering cylindrical tubes. This means a spacecraft would only have to worry about getting the device’s base onto the moon, with the actual tower rolled up inside.

The project is still in early stages of development here on Earth, but it is one of roughly a dozen initiatives chosen by DARPA for its 10-Year Lunar Architecture (LunA-10) Capability Study, which the agency launched last year. It seems inevitable that a new, human-influenced era is coming for the moon — but at least if projects like LUNARSABER come to fruition, it won’t be a dark age.