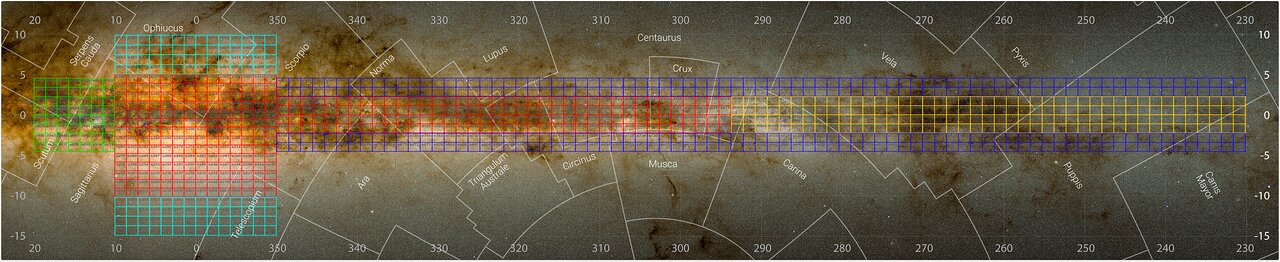

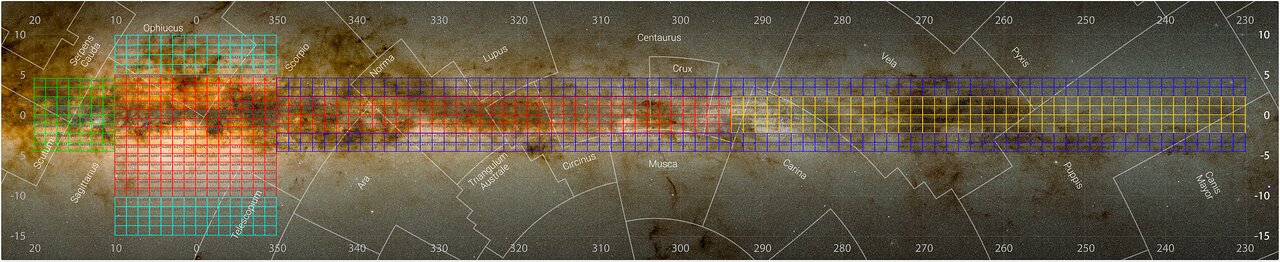

The most detailed infrared map of the Milky Way contains incredible images of over 1.5 billion objects within our galaxy.

The 200,000 images were collected by the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile over the course of over 13 years, from 2010 to 2023, as part of the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey and its companion project, the VVV Extended Survey (VVVX). The images were combined to form the record-breaking map, which covers an area of the sky equivalent to 8,600 full moons (as seen from Earth). For context, it contains ten times more objects than a similar 2012 map released by the same team of scientists.

“We made so many discoveries we have changed the view of our galaxy forever,” project leader Dante Minniti, an astrophysicist at the Universidad Andrés Bello, said in a statement.

VISTA was successful in seeing features of the Milky Way in unprecedented detail thanks to the capability of its VIRCAM. VIRCAM managed to peer through the dust and gas that permeates our galaxy — it was therefore able to see the radiation from the Milky Way’s usually hidden locations and painting a quite complete picture of our galactic surroundings.

Related: James Webb Telescope goes ‘extreme’ and spots baby stars at the edge of the Milky Way (image)

What can you see in the VISTA Milky Way map?

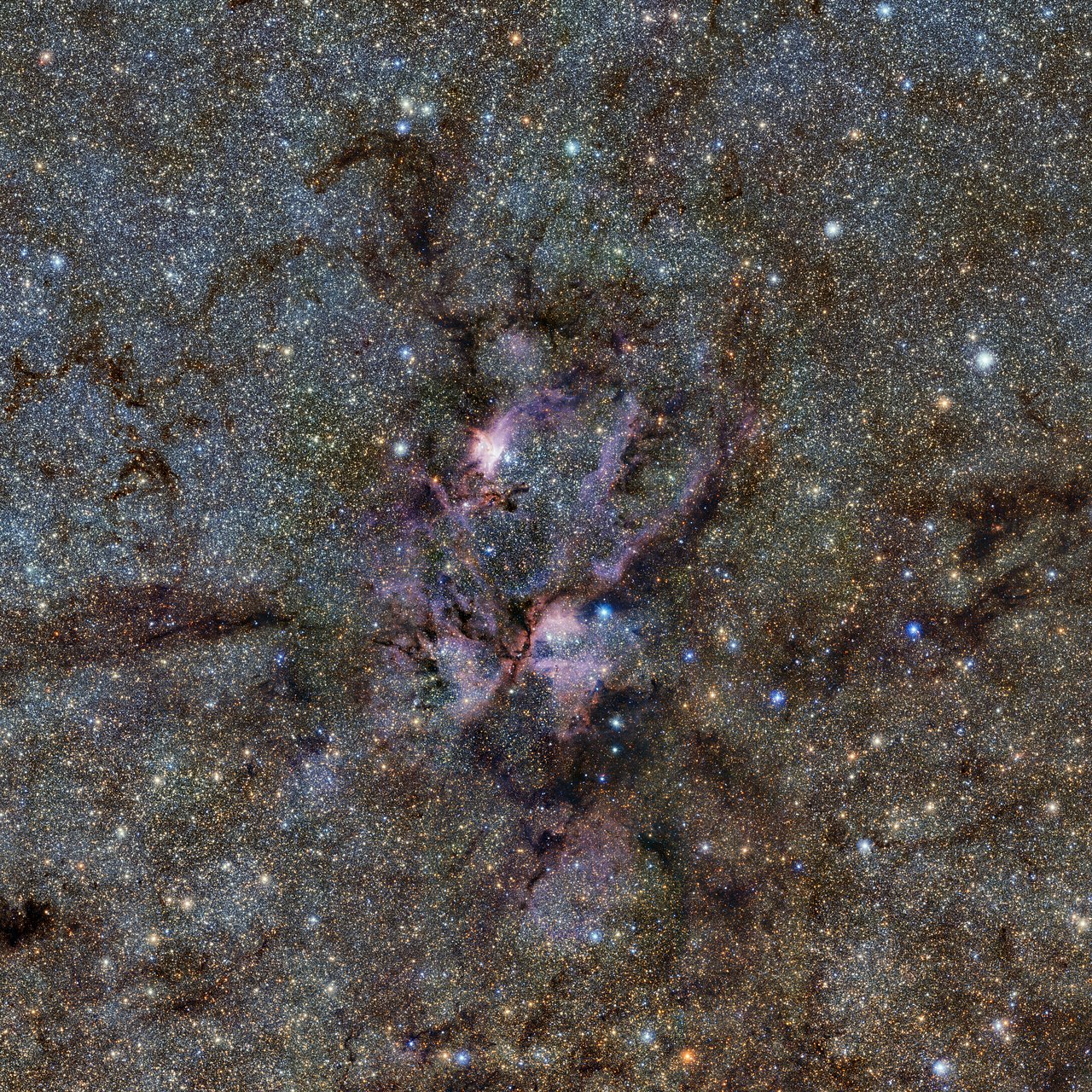

The new map of the Milky Way covers objects such as stellar nurseries packed with newborn stars still cocooned in their natal envelopes of gas and dust. These include the stellar nursery NGC 6357, also known as the “Lobster Nebula,” located around 5,900 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Scorpius.

Another of the star-forming regions of the Milky Way observed by VISTA as part of the survey is Messier 17, also known as the “Omega Nebula.” Located around 6,000 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Sagittarius, this cloud of star-forming gas is around 15 light-years wide, but it is part of a wider cloud of matter that is about 40 light-years wide.

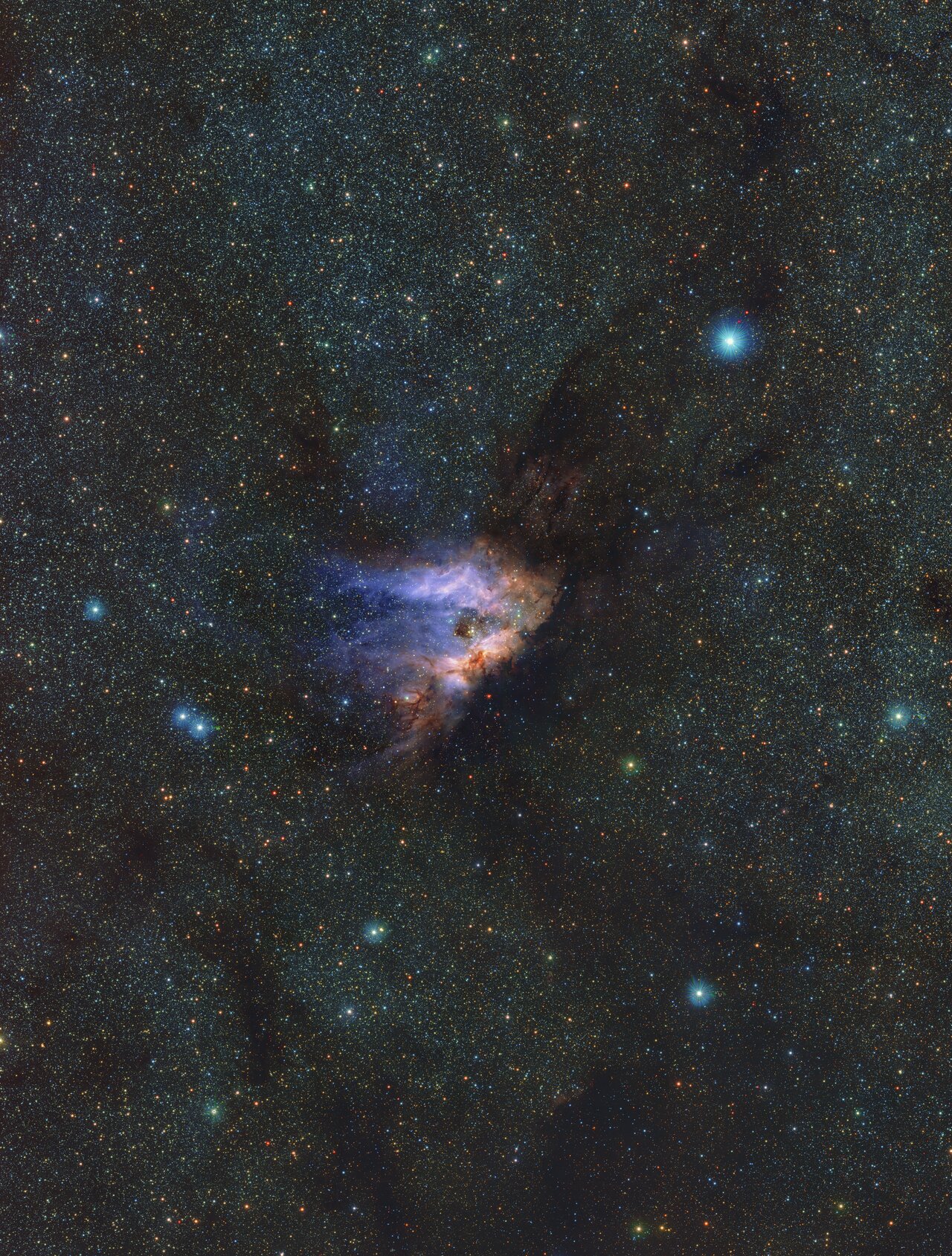

Also packed with bright young stars are the dual nebulas of NGC 3603, located around 20,000 light-years away, and NGC 3576, also known as the “Statue of Liberty Nebula,” located just 9,000 light-years away. NGC 3603 sits on one of the spiral arms of the Milky Way and just so happens to be one of the most massive young star clusters in our galaxy.

On the opposite end of the stellar age scale, the survey also captured images of more ancient stars.

Many of these are found in conglomerations called “globular clusters.” There are around 150 of these tightly packed ancient stars located in the Milky Way, thought to have formed from the same collapsing clouds of gas and dust.

One example of a globular cluster seen by VISTA as part of the 13-year-long survey is Messier 22, also known as NGC 6656, located around 10,000 light-years away from Earth. The stars of Messier 22 are thought to be leftovers from the early universe. That makes them some of the oldest known stars.

Messier 22 has some features that make it stand out among other globular clusters, too. It is host to at least two stellar-mass black holes and six free-floating “rogue planets,” that aren’t orbiting parent stars.

Additionally, Messier 22 is one of only four globular clusters that have been found to contain a planetary nebula. Despite the name, these have nothing to do with planets; they are actually the wreckage of massive stars that have exploded in tremendous supernova explosions.

For the 420 nights that VISTA conducted the VVV and VVVX surveys, the telescope revised the same patch of sky repeatedly. This allowed scientists to precisely determine the positions of the objects above (and many others) and track how they move throughout the sky as well as how their brightnesses change over time. The result is a peek through the dust that often obscures our view of our own galaxy, and a revolutionary three-dimensional map of the Milky Way.

“The project was a monumental effort, made possible because a great team surrounded us,” team leader Roberto Saito, an astrophysicist at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina in Brazil, said in the statement.

The team’s research was published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. The VVV data can be accessed here, while the VVVX data is available here.