A long-running leak is the top “safety risk” affecting the plan to keep astronauts on board the International Space Station until 2030, a new NASA audit found.

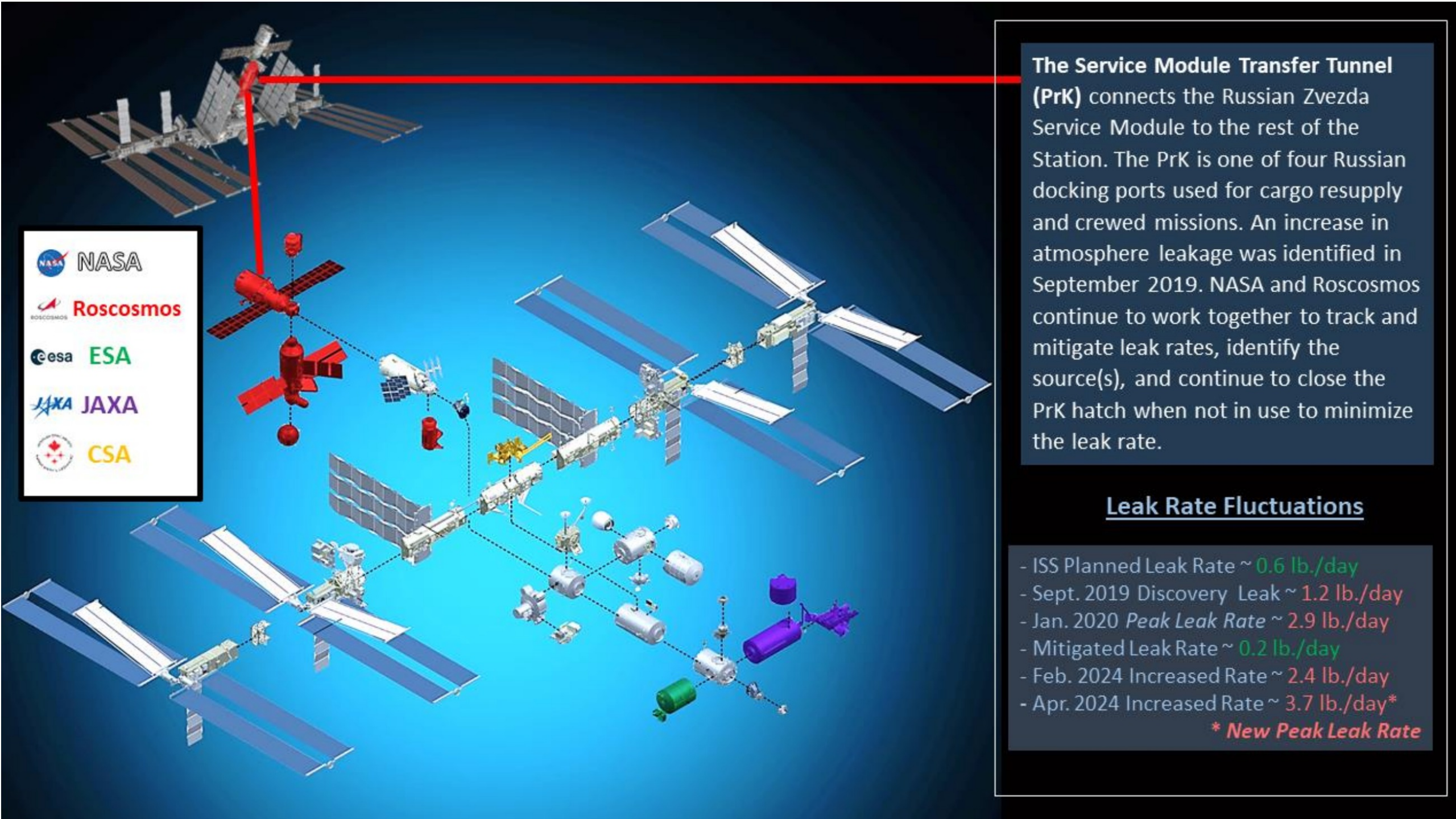

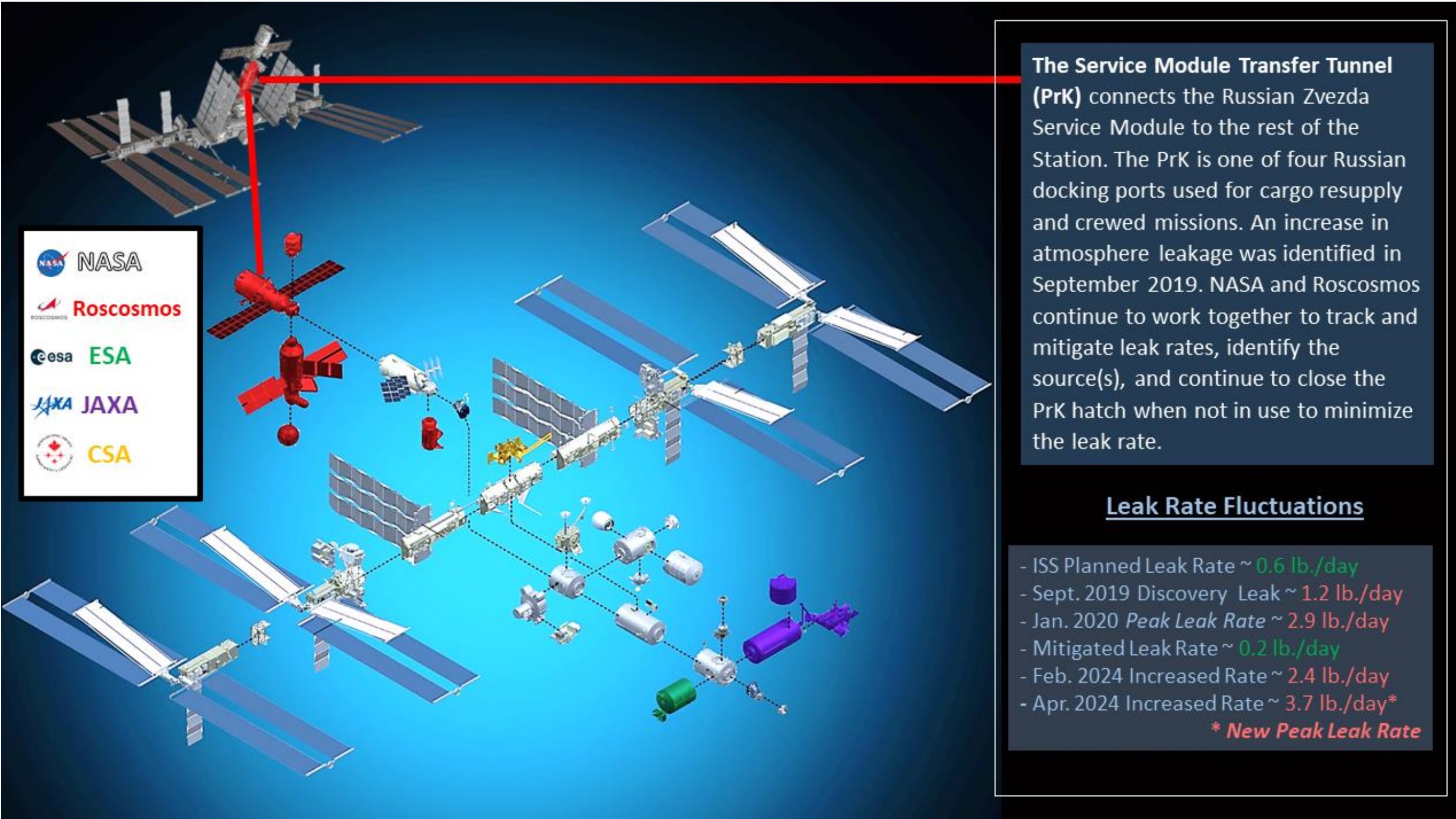

The affected area, found in the Russian segment of the International Space Station (ISS), has been leaking for five years and poses no immediate threat to astronauts, NASA officials have said. “Not an impact right now on the crew safety or vehicle operations, but something for everybody to be aware of,” ISS program manager Joel Montalbano said in February 2024 when the leak increased to 2.4 pounds per day, up from a historic low of 0.2 pounds per day.

Two months later, however, the leak increased by 50%, to 3.7 pounds per day, NASA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) stated in a new report released Sept. 26. “Ongoing cracks and air leaks” in that Russian module are being examined by NASA and the Russian space agency Roscosmos, the report emphasized, but officials warned that the aging ISS needs several measures to keep operations going through at least the complex’s planned retirement in 2030.

NASA officials recently said that the leak remains manageable, noting that more recent repair work after April 2024 reduced the all-time-high rate by roughly a third.

“We’ll continue to work with them [Roscosmos] to understand the sources of the leak and how they affect the operation of the space station,” Jim Free, NASA associate administrator, said in a Sept. 27 livestreamed briefing ahead of the SpaceX Crew-9 astronaut launch to the ISS that occurred the following day.

Related: How often does the International Space Station have to dodge space debris?

Yet the OIG report notes that the leak in Russia’s service module transfer tunnel, in the Zvezda module that launched in 2000, is emblematic of issues that affect the plan to keep the aging ISS going.

Like any older vehicle, the ISS requires maintenance and repairs, but the additional challenge is its extremely remote location. Anything from supply chain issues for repair items to a sudden micrometeoroid strike could pose a critical risk to the ISS, the report stated. And as of August 2024, NASA’s risk assessments put the tunnel at a scale of 5, the top echelon in its 1-to-5 ranking system.

The tunnel leak first arose in 2019, in an area that connects Zvezda to one of the space station’s eight docking ports. The OIG first issued a report on the leak in 2021, and since 2022, NASA has been making regular reports to its Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel of the agency’s efforts to address the leak.

Adjustments remained ongoing at the time the report was written: “NASA and Roscosmos are collaborating to investigate and mitigate the cracks and leaks, determine the root cause, and monitor the station for new leaks,” the OIG stated. While no root cause has been identified yet, “both agencies have narrowed their focus to internal and external welds.”

Roscosmos has said they can always close the hatch to the service module if the leak becomes “untenable”, but the OIG noted that NASA and its Russian counterpart have not yet agreed what leak rate constitutes an untenable threat. The ISS would lose a docking port if this scenario happened, which “could impact cargo delivery” and would also require “additional propellant to maintain the station’s altitude and attitude.” (Russian spacecraft docked at the port regularly fire engines to bring the ISS higher in its orbit, since Earth’s atmosphere slowly drags the ISS down over time.)

Aside from the leak, the OIG considered other risks to maintaining the ISS until 2030 and possibly extending it, depending on when NASA-funded commercial space stations are ready to replace the ISS. Commercial experiments in low Earth orbit are one of the primary drivers for space station operations, and past congressional discussions about the ISS have noted that China stands ready to scoop up the global research market should the U.S. not be able to maintain an orbiting outpost.

The OIG’s recommendations included reexamining space debris tracking practices, assessing how to bring crew members to and from the station should one of the commercial spacecraft from SpaceX or Boeing fail, and more measures to ready for the planned deorbit of the ISS.

Earlier this year, SpaceX was selected for a large Dragon-type spacecraft to remove the ISS from orbit. The OIG said it is interested in learning more about the costs, the schedule and risks in technical and planning matters with regard to the SpaceX vehicle and the overall deorbiting plan.