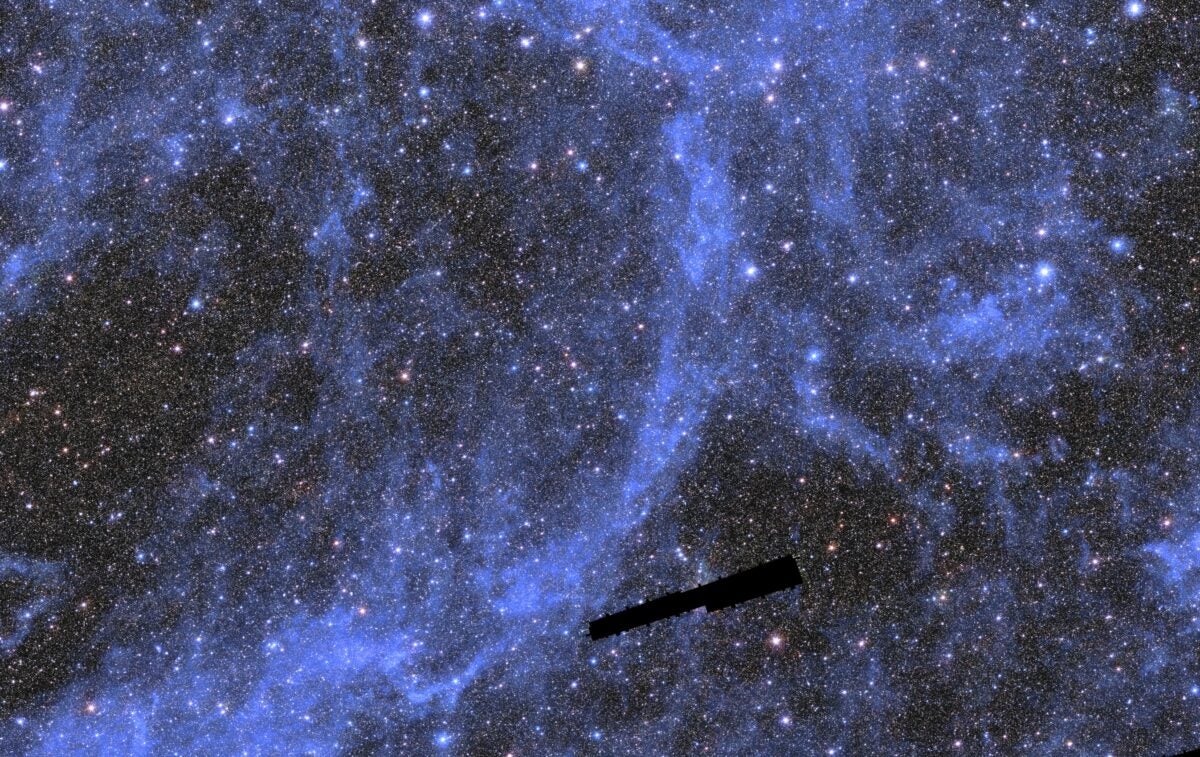

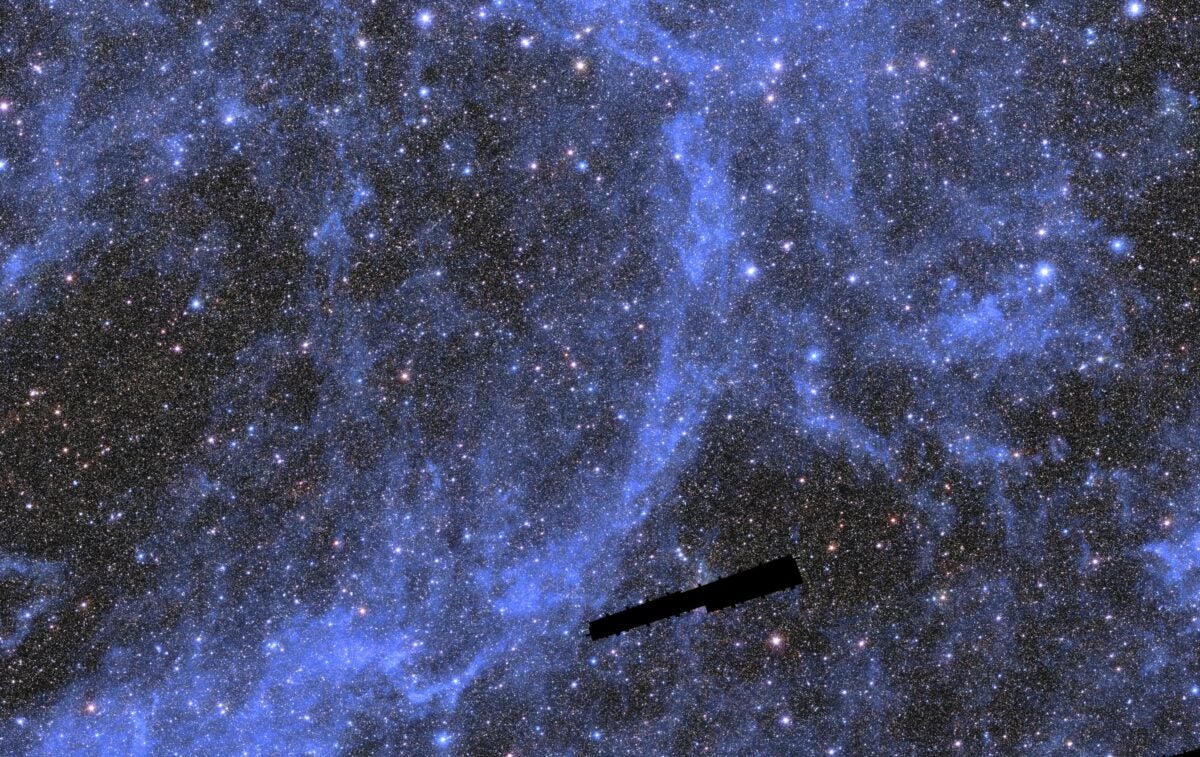

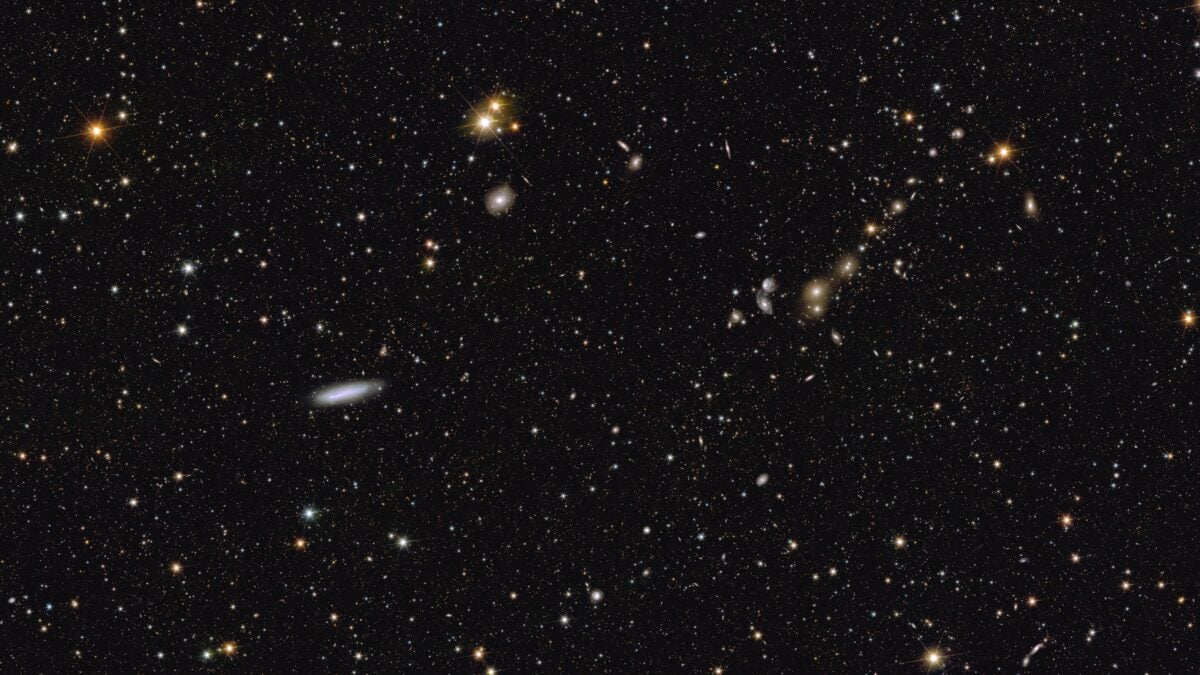

Stars and wisps of galactic gas fill this cropped view, representing just a small portion of a mosaic, released today, produced by the European Space Agency’s Euclid mission. Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, CEA Paris-Saclay, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre, E. Bertin, G. Anselmi CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

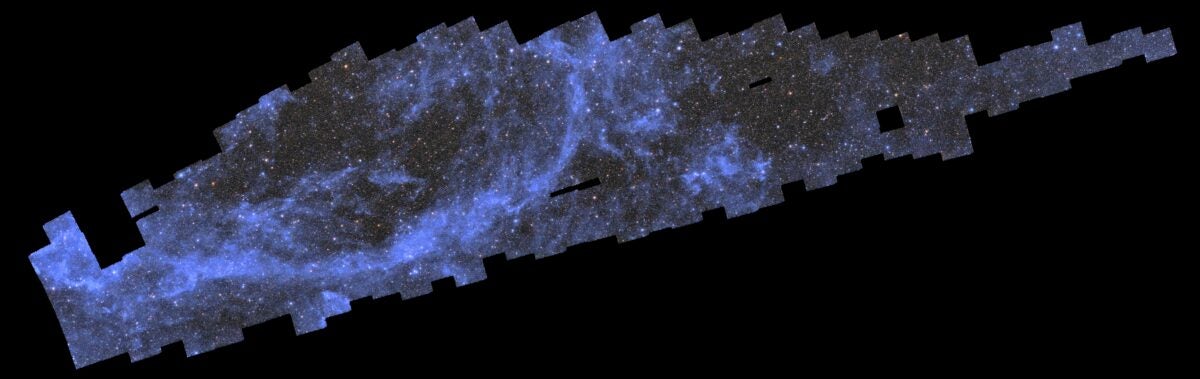

The Euclid space observatory launched in July 2023, tasked with creating a 3D map of more than a third of the sky, surveying billions of galaxies up to 10 billion light-years away. Today, scientists revealed the first page in its cosmic atlas, a mosaic comprising 208 gigapixels of data revealing billions of galaxies in awesome detail. The massive image is just 1 percent of Euclid’s full assignment, obtained across just two weeks of observing between March 25 and April 8 of this year.

Top officials at the European Space Agency (ESA) — which built and operates Euclid — revealed the image today at the International Astronautical Conference in Milan, Italy.

“Euclid has turned its keen eye to the sky and is working through its observation program,” said physicist Frank Grupp, Euclid’s German project manager, in a press release. “Scientists and engineers are happy to be able to reap the rewards of 15 years of preparation.”

Looking for the dark

Euclid scans the cosmos in visible and near-infrared light, including an infrared spectrometer, which allows it to measure the composition and motions of targets in detail. Its primary mirror is 1.2 meters (4 feet) across, allowing it to reveal galaxies up to 10 billion light-years away, when the universe was in its childhood.

The telescope orbits the distant Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point 0.9 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away, keeping company with other observatories designed to peer into the deepest corners of space, including NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and ESA’s Gaia.

Euclid is tasked with answering major cosmological questions about the makeup and evolution of the universe. Scientists understand, from previous missions such as ESA’s Planck satellite, that 68 percent of the universe is dark energy, a mysterious substance that drives the accelerating expansion of our reality. Astronomers noticed the omnipresent expansion of the universe in the early 20th century and eventually traced it backward to discover the Big Bang.

But it wasn’t until the tail end of the 20th century that astronomers noticed that this expansion is speeding up. How or why the acceleration is occurring still isn’t understood. The best scientists have done is give the force that causes it, pushing the universe’s stuff ever farther apart, a name: dark energy. And whatever dark energy is, it kicked into high gear when the universe was some 9 billion years old, a timeframe easily encompassed by Euclid’s view of 10 billion years of cosmic history.

By mapping the evolution of galaxies — their sizes, shapes, and how they cluster together — from the universe’s early days until the present, Euclid should obtain an unprecedented view into how the universe as we know it came to be.

While the observatory’s overall mission is cosmological, its detailed imagery over wide swaths of the sky will also reveal information on individual galaxies, star populations, supernovae, exoplanets, the dimmest brown dwarfs, and many examples of gravitational lensing.

Zooming in

The image released today combines 260 observations containing some 14 billion galaxies, as well as tens of millions of individual stars closer to home. The mosaic image is not fully zoomable, but ESA has provided visual stepping stones, allowing the public to walk deeper into Euclid’s view of the cosmos, seeing galaxy clusters and then individual galaxies emerge in exquisite detail.

CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

“This stunning image is the first piece of a map that in six years will reveal more than one third of the sky,” said Valeria Pettorino, Euclid Project Scientist at ESA, in a press release. This is just 1 percent of the map, and yet it is full of a variety of sources that will help scientists discover new ways to describe the Universe.”

The 6-year survey will encompass over a third of the sky, turning away from the Milky Way’s bright central regions and focusing on the dark edges of the universe. Euclid’s final atlas will also contain deep-field regions similar to Hubble’s famous images of the darkest, farthest, oldest corners of space.

The first year of cosmology data is scheduled for release in 2026, after the Euclid team has had time to reduce the massive amounts of information returned by the telescope — as much as 100 gigabytes of data every day.

The public can look forward to another 53 square degrees of Euclid’s view of the sky in March 2025, where the mission will show off its first deep-field imagery. In the meantime, Euclid will continue its quiet contemplation of the cosmos’ deepest mysteries.