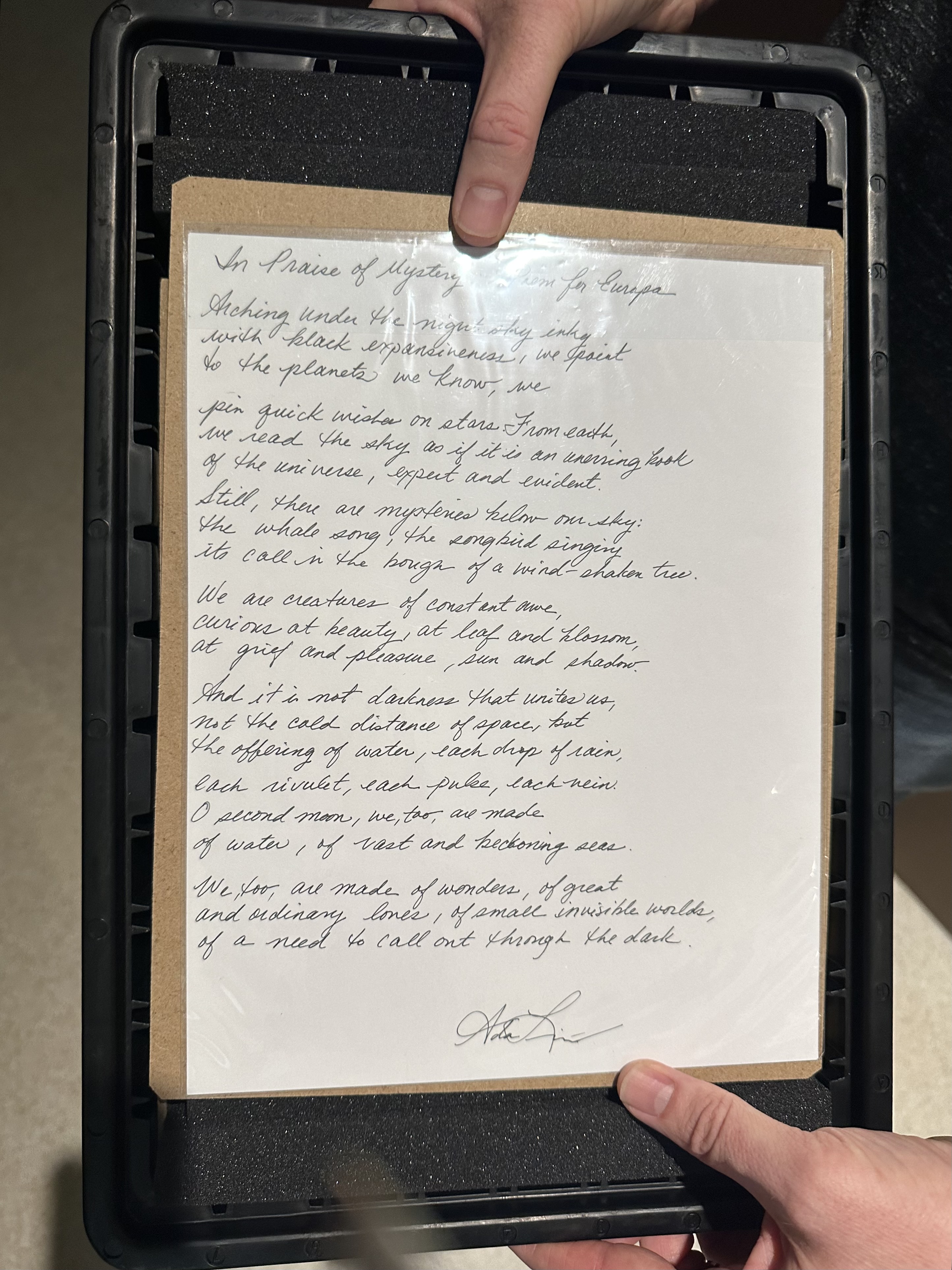

A metallic plate about the size of a standard sheet of printer paper is bolting through space as you read this, engraved with the thoughts of U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón:

“Arching under the night sky inky

with black expansiveness, we point

to the planets we know,”

Indeed, this slate gray plate is headed toward a world that has plagued humanity’s dreams since the dawn of astronomy: our solar system’s sunset-hued gas giant, Jupiter. It’s attached to a spacecraft called the Europa Clipper, NASA’s solar-winged, silvery probe built to study the intricacies of a Jovian moon that could have harbored life long ago, per scientists’ calculations. That probe launched on its mission on Oct. 14; it’s somewhere in the vastness of space now, on its way to Europa.

But the sturdy plate — inscribed with far more than the poignant words of Limón — also has a twin that sits on our planet. The replica is at the Brand Library & Art Center in Glendale, California, and the simple fact that it exists invites us to ponder the peculiar gap between art and science, or lack thereof.

“we / pin quick wishes on stars. From earth,

we read the sky as if it is an unerring book

of the universe, expert and evident.

Still, there are mysteries below our sky:

the whale song, the songbird singing

its call in the bough of a wind-shaken tree.”

Related: The artist who sculpted the 4-dimensional fabric of space and time

If you take this train of thought to the most extreme level, you may argue that quite literally everything is artwork, and that the entire topic of this story is moot. You could perhaps also argue that quite literally everything is scientific, leading to the same conclusion.

The way tiny vibrations in your house can make water ripple within a Poland Spring bottle is strangely mesmerizing when focused on, the general reflective properties of mirrors are consistently tapped on in artist exhibitions, and the Gauss-Bonnet theorem, which is used to describe the curvature of complex shapes, is often referred to by mathematicians as “beautiful.” Even psychological concepts, like the inexplicable qualia that comes with new physical experiences, can be deemed “artistic.” What, intrinsically, is only science or only art?

“We are creatures of constant awe,

curious at beauty, at leaf and blossom,

at grief and pleasure, sun and shadow.”

Maybe there’s a way to attempt to find the border between the two subjects, and maybe it’s a subjective one. In my eyes, art, at a foundational level, could be considered the pursuit of aesthetics, while science, at its foundational level, could be considered the pursuit of knowledge. Still, of course, I feel there are crossovers — I’d say both are easily considered the pursuit of truth. Philosophers, artists and scientists have argued over these kinds of questions for decades, and we certainly won’t get to the bottom of it in this article.

However, what about the division between art and astronomy specifically? It’s interesting how the lines seem further blurred.

Unlike botany, for example, astronomy is a subject in which we have to imagine our targets most of the time. Even though we can’t see chlorophyll with our unaided eyes, we can see the leaves it’s contained in with great ease; on the other hand, we cannot glimpse a black hole event horizon, a diamond-encrusted exoplanet or a horsehead-shaped crevice of a nebula for what they are — at least, with our current technology. (Even Albert Einstein didn’t think we’d witness the gravitational waves that ripple across the universe when two black holes collide, but then we did in 2015. It is no wonder that astronomy and faith were far more tethered during ancient times than they are today.)

Furthermore, defining the edge of the universe might be a mystery we may never solve, and by nature of being human, we can’t exactly comprehend light-year-long distances — research has even shown that physicists’ brains work differently than non-physicists’ because the former have to continuously think about unfathomable scales. And unlike many other scientific topics such as mineralogy or clinical medicine, astronomy also has the potential to explain our existence on the grandest of terms.

Yet astronomy attempts to elucidate these somewhat ineffable concepts much in the same way art attempts to express the ineffable through images, sound, words or any other medium — in turn, both cultivate a certain profound, unsettling and existential feeling in us, and we chase that feeling. Of course, there are always going to be arguments made in different directions, but at its root, analyzing space seems to evoke something in us that analyzing other scientific subjects does not.

Cosmic discoveries can offer both reprieve and anxiety, as well as a sense of unity mixed with uncanny loneliness. And I think art has the unique ability to mimic that, and often aims to mimic that.

This is why it is particularly moving when astronomy and art are purposely melded together. The Voyager Golden Records left the solar system in the summer of 1977 while holding proof of humanity taking up space in the cosmos, carrying images of Olympic sprinters and someone eating grapes at the supermarket, clips of a Peruvian wedding song and Louis Armstrong’s “Melancholy Blues” — and to this day, they make humans emotional. Not only did these records transcend the standard definition of space exploration, but they also proved that there is something special, and even artful, about humanity as a whole — something crucial enough to be brought into the void of the universe that humanity itself meditates upon.

In addition to Limón’s poem, the Europa Clipper’s plate — made of a material called “tantalum” that can withstand the heavy amounts of radiation found near the spacecraft’s destination — holds an engraving of The Drake Equation. Written in the handwriting of late astrophysicist and astrobiologist Frank Drake, this equation is a mathematical formula related to finding intelligent civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy. It’s an apt reference, seeing as the Europa Clipper’s primary astrobiology mission is to see whether or not Europa exhibits signs of habitability. The spacecraft won’t be looking for proof of life, but rather proof that this world is conducive to hosting life (as we know it).

It also carries a sketch of Ron Greeley, who founded the field of planetary science and helped the Apollo astronauts reach the moon, and a silicon chip with 2.6 million names of Earthlings who signed up to have their being brought beyond Earth somehow. Most strikingly, one entire side of the plate is engraved with waveforms of the word “water” spoken in different languages.

“And it is not darkness that unites us,

not the cold distance of space, but

the offering of water, each drop of rain,

each rivulet, each pulse, each vein.

O second moon, we, too, are made

of water, of vast and beckoning seas.”

The Europa Clipper’s plate is certainly important because, well, maybe it will allow aliens with the right tools and enough curiosity to find a trace of us in the Jovian system someday — but it’s also important in the short-term. This rich object has already provided us with the “something” for which we rely on astronomy, and on art.

“We, too, are made of wonders, of great

and ordinary loves, of small invisible worlds,

of a need to call out through the dark.”

The trip to the Brand Library & Art Center was funded by The Getty Museum as part of the PST: Art and Science Collide event.