25/10/2024

480 views

18 likes

New research, partially funded by ESA, reveals that the cool ‘ocean skin’ allows oceans to absorb more atmospheric carbon dioxide than previously thought. These findings could enhance global carbon assessments, shaping more effective emission-reduction policies.

The global ocean absorbs roughly a quarter of carbon emissions from human activities, which is extremely important in helping to slow climate change. On the flip side, however, this benefit does come at a cost: as oceans take in more carbon, their waters become more acidic, endangering the health of marine ecosystems.

Enhancing our understanding of the complex processes driving sea–air carbon fluxes and refining estimates of how much carbon the global ocean sequesters are crucial for accurate carbon budget assessments and informed climate action.

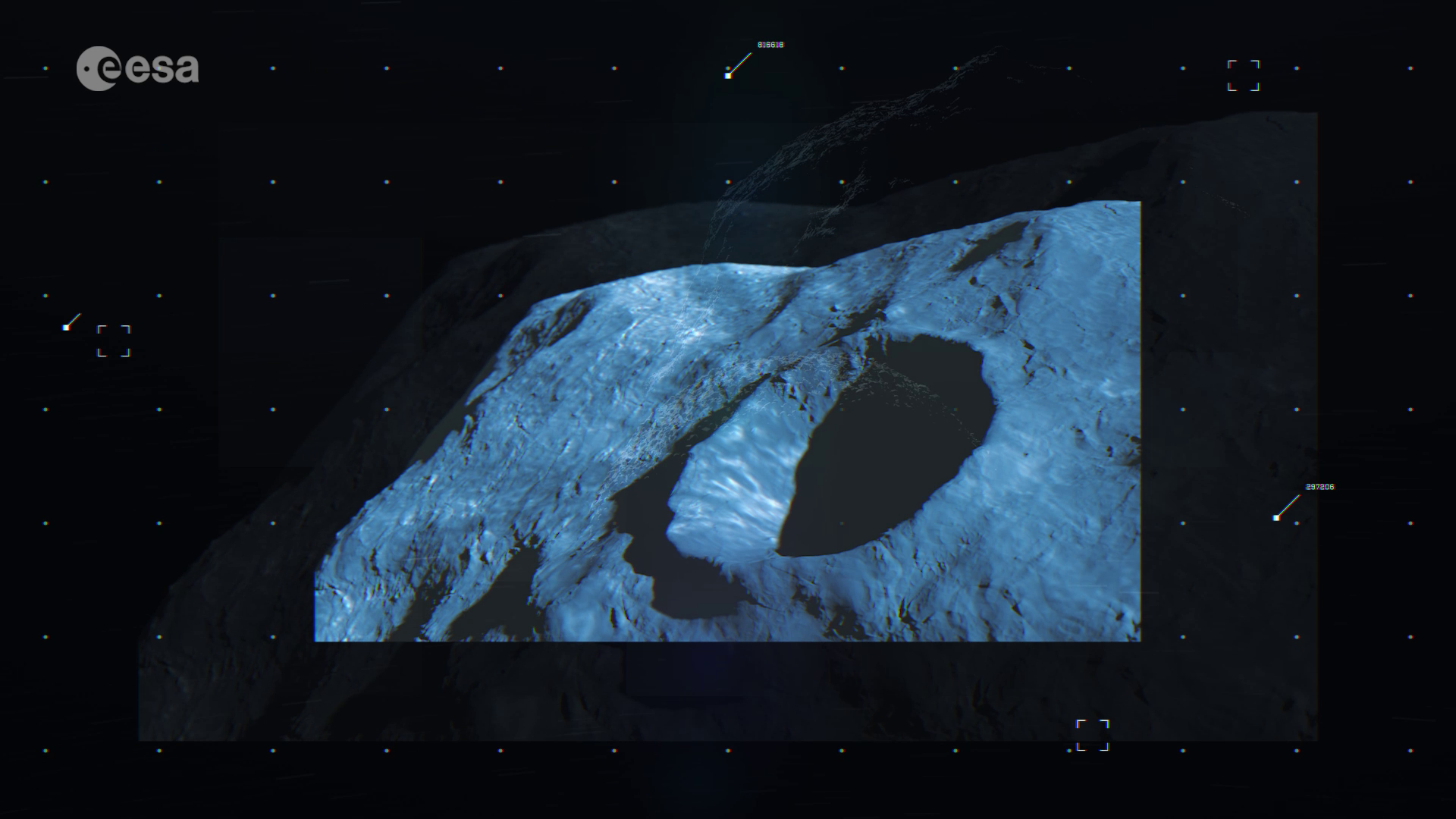

Scientists have thought that the ocean skin – a 0.01 mm sliver of surface water, thinner than a human hair, which is typically fractionally cooler than the water below – should increase the amount of carbon dioxide being absorbed from the atmosphere.

This is because cooler water is more efficient at absorbing carbon dioxide. The gas concentration between this thin top layer and the water some 2 mm deeper is what controls the exchange of the gas between the atmosphere and the ocean.

However, this had never been extensively measured at sea, until now.

Thanks to research, which was partially funded by ESA, scientists from the UK’s University of Exeter, Plymouth Marine Laboratory and University of Southampton assessed in situ measurements taken from ships as they traversed the Atlantic Ocean.

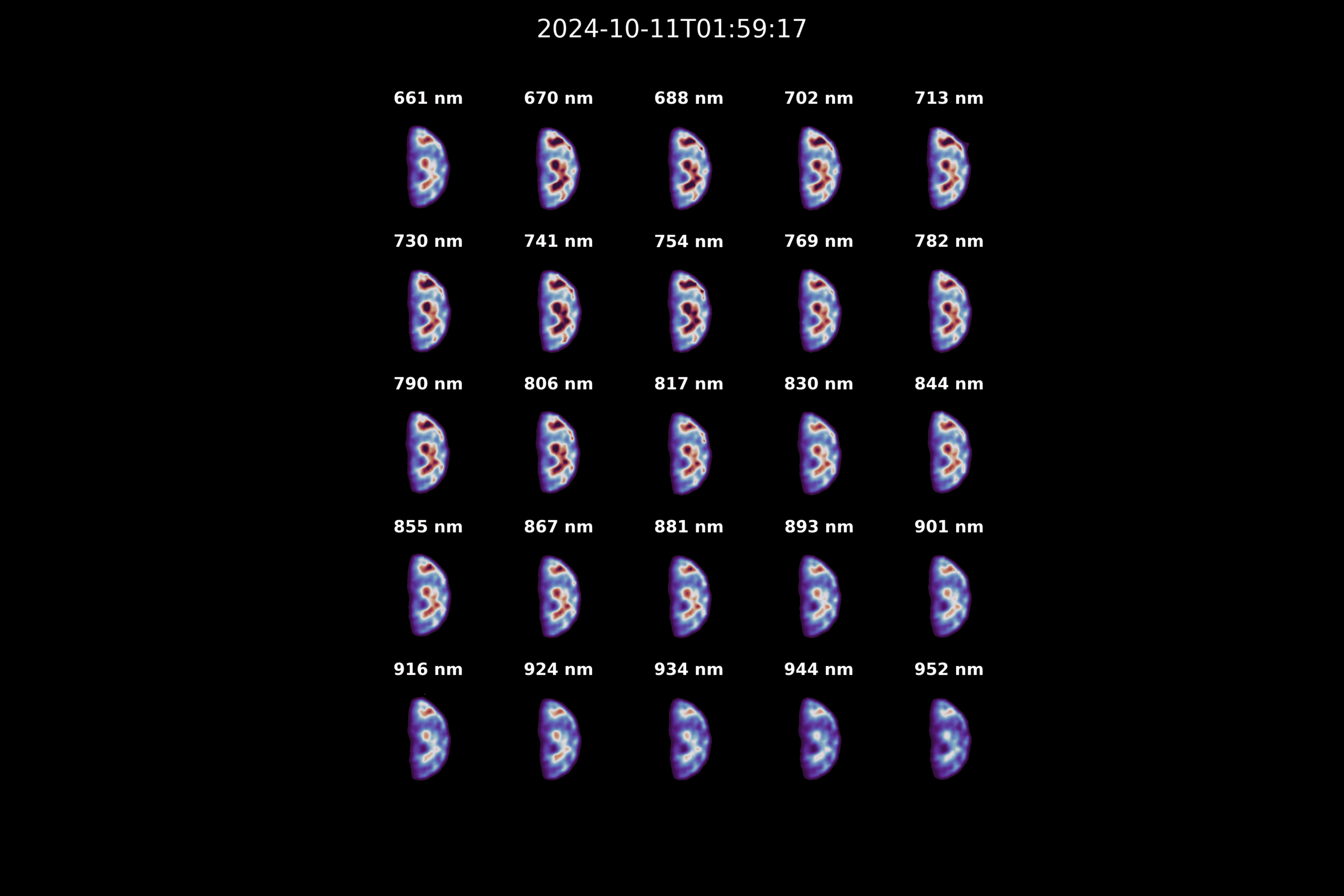

The measurements were taken by flux systems that detected tiny differences in carbon dioxide in air swirling towards the ocean surface and away again, along with precise temperature readings of the extremely thin ocean skin.

Based on these measurements, the new findings, published today in the journal Nature Geoscience, confirm that that the temperature of the ocean skin increases carbon absorption.

The results suggest that the ocean absorbs about 7% more carbon dioxide each year than previously thought due to the cool skin of the surface. This might sound small, but when integrated across all oceans, this additional carbon absorption is equivalent to one and half times the carbon captured by annual forest growth in the Amazon rainforest.

Currently, global estimates of air–sea carbon dioxide fluxes typically ignore the importance of temperature differences in the near-surface layer.

Daniel Ford, from the University of Exeter, said, “Our findings provide measurements that confirm our theoretical understanding about carbon dioxide fluxes at the ocean surface.

“With the COP29 climate change conference taking place next month, this work highlights the importance of the oceans, but it should also help us improve the global carbon assessments that are used to guide emission reductions.”

Ian Ashton, also from the University of Exeter, said, “This work is the culmination of many years of effort from an international team of scientists. ESA’s support was instrumental in putting together such a high-quality measurement campaign across an entire ocean.”

Gavin Tilstone, from Plymouth Marine Laboratory, added, “This discovery highlights the intricacy of the ocean’s water column structure and how it can influence carbon dioxide draw-down from the atmosphere.

“Understanding these subtle mechanisms is crucial as we continue to refine our climate models and predictions. It underscores the ocean’s vital role in regulating the planet’s carbon cycle and climate.”

ESA’s Craig Donlon noted, “Measurements of the cool skin of the ocean and precision atmosphere-ocean fluxes made together aboard a ship is an incredibly challenging task.

“The implications of these results are profound in terms of carbon accounting – which currently pays little attention to the role of the ocean surface.

“With the issue of climate change more pressing than ever, these results will help improve our understanding and assessment of the complex role that the oceans play in regulating the climate, and to take action.”

This research was funded by ESA’s Science for Society initiative, Horizon Europe and the UK Natural Environment Research Council. The ship cruises were part of the Atlantic Meridional Transect project led by the Plymouth Marine Laboratory.