“There is every reason to believe China’s BeiDou global navigation satellite system has the ability to imitate American GPS signals and those of Europe’s Galileo,” said Professor Todd Humphreys of the University of Texas Radionavigation Lab. Humphreys was speaking at The Department of Transportation’s annual Civil GPS Service Interface Committee meeting, held for the public this September in Baltimore. He also discussed a long-term Russian project to put a nuclear-powered electronic warfare weapon in orbit that could do the same thing.

Broad adoption of GPS signals over the last 40 years for use in everything from weapons systems to electrical grids and industrial controls have made them prime targets in conflict zones. By preventing reception (jamming) or sending false GPS signals (spoofing), belligerents can degrade or disable munitions, redirect drones and missiles and degrade IT systems and other infrastructure.

Unlike many of its adversaries, the United States has made few preparations for such attacks on its homeland and infrastructure, despite mishaps at home that have disrupted air traffic control systems and regular press reports of American weapons systems degraded by jamming and spoofing overseas.

Open conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, Kashmir and Myanmar demonstrate the utility of this kind of cyber and electronic warfare every day. Vladimir Putin’s regular GPS jamming and spoofing in the Baltic also shows its usefulness as a tool for discrediting the systems and institutions of one’s opponents in a form of low-level, hybrid, non-kinetic warfare. These should be daily reminders of the peril of the U.S.’s inaction.

Interference with GPS signals has greatly increased over the last ten years, dramatically so since 2021. Since there are many incentives for malicious actors and few easy countermeasures, many experts like Humphreys see the activity continuing to grow. While most interference to date has seemingly come from equipment on Earth, experts predict that this activity will likely expand to space-based sources.

GPS and the signals that interfere with it require line-of-sight access. Because of this, while some infrastructure and terrestrial systems have occasionally been affected to date, the vast majority of impacts have been to aircraft and ships not shielded by terrain.

The dangers of space-based GPS disruptions

Jamming or spoofing from space would have a much broader impact, potentially affecting every receiver in the area targeted. Even multi-element antennas used to help receivers ignore bad signals from one direction could conceivably be neutralized because the interference would be coming from everywhere. This would have immediate and devastating impacts on broad geographic regions like Europe or the continental United States.

GPS signals are incredibly weak, so a little bit of radio noise broadcast at the right frequency is often enough to prevent reception. And, since the U.S. government made GPS a “gift to the world,” the exact nature and specifications for the signals are public knowledge.

The U.S. military has known about the possibility of GPS signals being manipulated since the early days of the program. In 1995, only two years after GPS became operational, the MITRE Corporation responded to Department of Defense concerns with the paper “Techniques to Counter GPS Spoofing.” This became a benchmark document still referenced within the cleared tech community.

For a long time, spoofing wasn’t much of a concern. But the advent of inexpensive digital technology and software-defined transmitters has made imitating GPS signals relatively cheap and easy. Even a reasonably competent hobbyist can now spoof many receivers into thinking they are somewhere they are not.

There are a number of reasons to believe this technology or something like it has been incorporated into China’s BeiDou, the world’s newest GPS-like system.

A close look at BeiDou

When BeiDou satellites were first launched in 2015, Europe was still in the process of fielding its Galileo global navigation satellite system. Researchers there were interested to learn as much as they could about the Chinese effort. During one set of observations, some researchers reportedly noticed the Chinese satellites transmitting GPS and Galileo-like signals. Spoofing had not yet become a disruptive global phenomenon, and the researchers did not connect the incident with the potential for malicious activity. So, it was never formally reported. When asked about their observations recently, they either declined to comment or spoke only on the condition of anonymity.

Others have affirmed Humphreys’s observation about BeiDou’s likely capabilities.

During a discussion on the topic prior to the Department of Transportation meeting, a researcher at the German Aerospace Center, DLR, observed that “[BeiDou] satellites and signals seem very flexible. It wouldn’t take much effort, and I would not be surprised if they could imitate signals from another constellation.”

Similarly, a researcher in the U.S. commented that international efforts to make the world’s global navigation satellite systems interoperable has naturally pushed them closer to being able to transmit each other’s signals.

“Everyone is sharing the same center frequency, and spectrum, and similar waveforms,” the researcher, who asked not to be identified, told me. “All this meant that, in pursuit of coexistence and interoperability, we have essentially taken all constellations 90% of the way to being able to mimic one another. The residual effort to “spoof” another system is actually quite small. It’s a wonder it has taken this long to get attention.”

Russian space-based threats

While Russia’s GLONASS satnav system is much older and less capable than China’s, the Putin regime seems to be pursuing its own course for being able to deliver knockout blows to GPS, as Moscow threatened it would do in November 2021 if NATO crossed its red line and interfered with the invasion of Ukraine.

In February, Congressman Mike Turner (R-OH) warned about Russia’s plans to place a nuclear weapon in orbit. Subsequently, the administration announced that this was a planned kinetic anti-satellite weapon — not a threat to Americans on the ground.

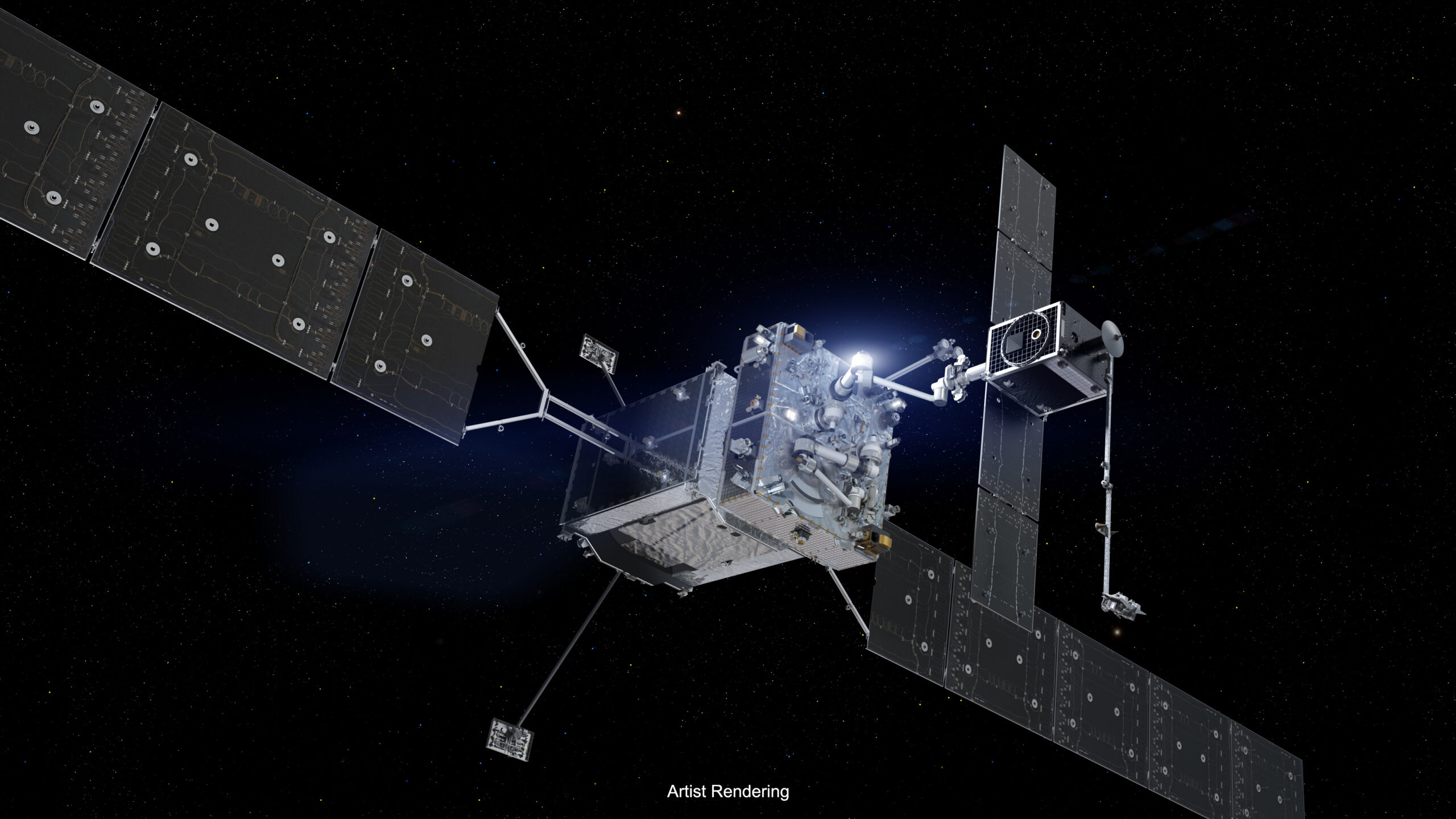

Less well known, and something also mentioned by Humphreys at the meeting, is a Russian project called Ekipazh or Zeus. A nuclear-powered electronic warfare satellite that would likely be able to jam GPS signals across a significant portion of the globe or subtly spoof them. According to the most recent publicly available reporting, test flights for the system had been planned for 2021.

Other perspectives

The potential for these kinds of threats and attacks on GPS from space has been considered by others.

In a recent paper about navigation warfare the National Security Space Association discussed the possibility and said “A space-based EW (electronic warfare) weapon could have devastating impacts to the U.S. homeland.”

Retired U.S. Air Force General William Shelton, a member of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation Board of Directors, was the commander of the service’s Space Command from 2011 to 2014. When I asked about the possibility of China’s navigation satellites also being able to transmit signals to interfere with or imitate GPS, he told me, “I don’t see why they wouldn’t build their satellites that way.” He also thinks there is a real possibility that Russia has or soon will put a powerful electronic warfare satellite in space.

When I asked if the U.S. has developed and deployed similar technologies, he said, “I certainly hope so!”

Dana A. Goward is President of the non-profit Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, and a member of the President’s National Space-based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board.