Yerkes Observatory and one of its domes sits atop a hill in Williams Bay, Wisconsin. All photos taken by Samantha Hill

The town of Williams Bay, Wisconsin is much like any other small city on a lake, with an offering of tourist shops and an active beach. But just a short drive past the activity brings you to Yerkes Observatory. Behind an opening of trees stands a sprawling, grand estate with a well-manicured lawn and a large, ornate building sitting proud atop a small hill overlooking the water.

Although it is one of the more ornate buildings in southern Wisconsin, Yerkes Observatory fell out of favor with its previous owner, the University of Chicago, because of its expensive upkeep and less-than-ideal location. The school eventually closed the observatory in 2018. However, the community of Williams Bay was adamant that the property would not become another shopping center or generic apartment building. Instead, the Yerkes Future Foundation was born. From money raised by various donors and locals, the historic observatory opened its doors to the public once more in 2022. The foundation now uses this historic site as a bridge to future scientific exploration.

Creating a legacy

In 1892, the prominent astronomer George Ellery Hale started the astronomy department at the newly-established University of Chicago. About the same time, the school came into possession of the largest telescope in the world, the 40-inch refractor, following the display of the mounting and tube for the telescope at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. With the world’s largest refractor and a new program underway, the school set about to establish an observatory. The establishment of Yerkes Observatory resulted from monies courtesy of Charles Yerkes, the “most hated man in Chicago.”

Yerkes, the key financier of streetcar systems in Chicago at the turn of the century, was notorious at the time for kicking people out of their homes, taking bribes, and having multiple affairs, among many other loathsome behaviors. In an attempt to raise his standing within the city’s high society, he donated the funds to build the observatory, as long as it was constructed within 100 miles of Chicago. And although he only visited the observatory once when it opened in 1897, and left the Midwest to distance himself from his misdeeds, his name lives on today. (His visage can also be found on the building’s exterior in some decorative gargoyles that depict Yerkes himself. Other gargoyles depict the university’s former president, William Harper, as well the unflattering and embellished features of John D. Rockefeller.)

Hale’s influence over years caused the university’s astronomy department to grow a robust astrophysics program complete with labs, offices, classrooms and multiple observation areas. And its huge refractor was the largest telescope in the world for close to a decade, and remains the largest refractor ever built. Hale was not the only big-name astronomer to study or work for the institution at one time or another. The list also includes Carl Sagan, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Nancy Grace Roman, Edwin Hubble, and Edward E. Barnard.

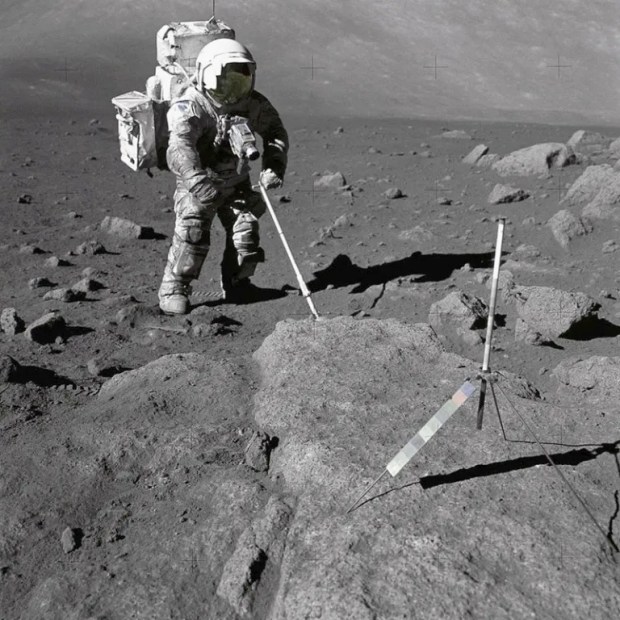

In the 1960s Yerkes added a 41-inch reflector to the observatory. However, as the years wore on, technology sped ahead and terribly increasing light pollution affected the observatory, and staff focused more on astrophysics. This work included efforts toward NASA’s now-retired Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).

By the time the university donated the observatory to the preservation group in 2019, it had already attempted to sell the property to land developers. However, due to a strong community outcry, the observatory remained in the school’s possession before delivering possession to the foundation.

Time capsule

I recently visited Yerkes Observatory. As I entered the building, the experience almost reminded me more of a church or a library because of the delicate array of stonework, its mythological creatures, celestial patterns, religious iconography, and other unique designs lining the ceilings. This seems to stand in contrast with the many practical scientific instruments deep within the building.

During a tour of the building (which is open to the public with a fee), it was clear that the Yerkes Foundation wants to faithfully preserve the building’s history. This includes a treasure trove of glass plates with priceless images of the cosmos.

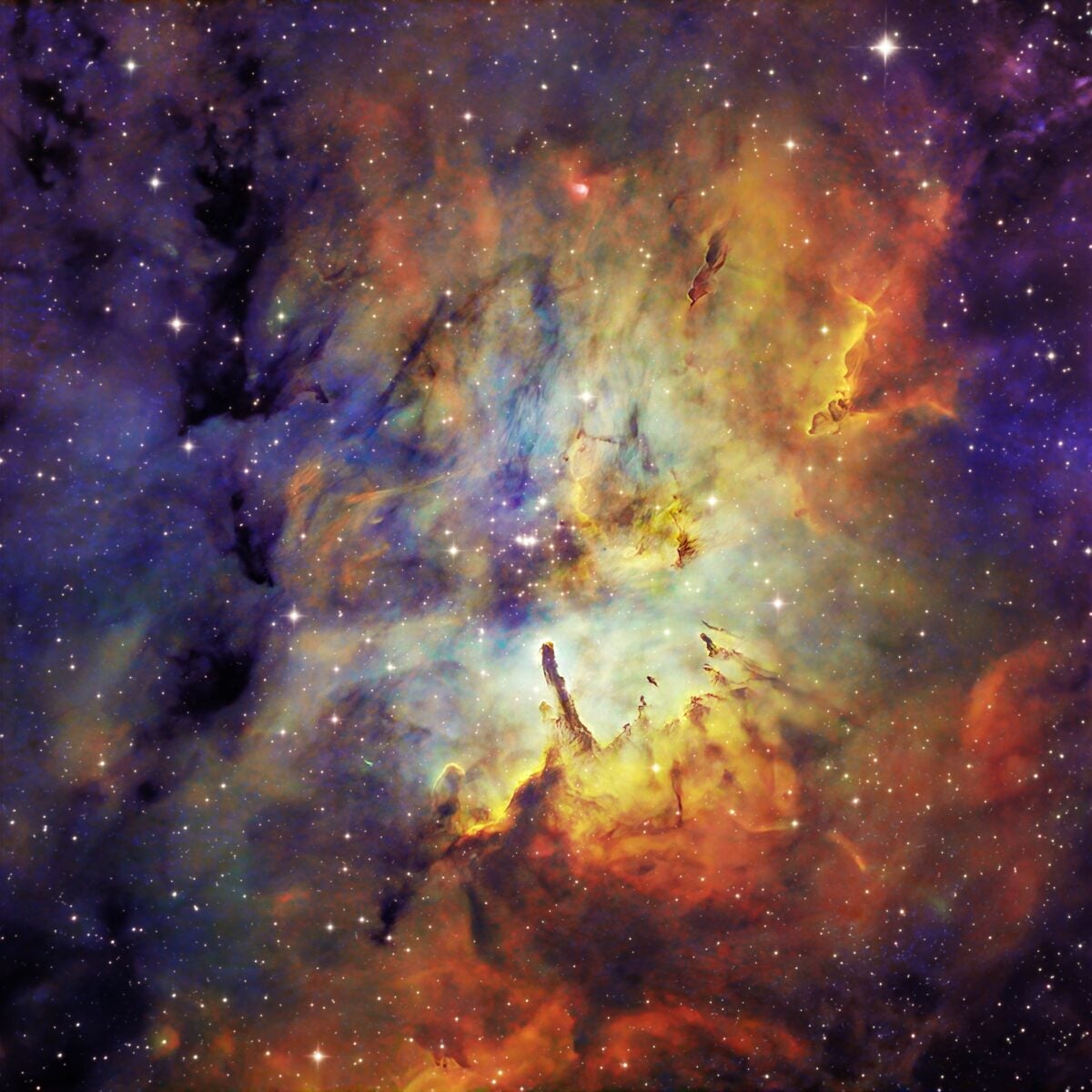

In the early days of observing, glass plates, usually the size of an average picture frame, would be coated in photosensitive chemicals and then exposed to light in a telescope or camera for long periods, capturing faint sky images. This painstaking process was an important aspect of collecting data because multiple plates would often be taken of the same objects that would then be compared to show any changes. The 180,000-piece collection contains a bevy of objects such as comets, spiral galaxies, star clusters, and planets. Even the glass from one of the observatory’s windows was used as a quick replacement for a plate during a solar eclipse and remains in its original location today.

With the advent of digital processing, glass plates became outmoded. Only until recently have the plates become archival tools, holding significant time capsules of changes to stars, galaxies and nebulae over time. Through student internship programs and volunteers, the Yerkes Foundation hopes to eventually digitize the collection.

Through a labyrinth of hallways, stairways, and Hale’s solar observing contraptions, visitors to the observatory are taken to the dome of the 41-inch reflector. Although the telescope does still work, it is now operated via computers — the switchboard located beside the telescope is just for show, still looking similar to how it did when it was installed more than a half-century ago.

As our group was examining the telescope, we were reminded of just how the sizes of more modern telescopes have changed. “Remember the size of this when we go see the other telescope,” said Dennis Kois, executive director for the Yerkes Foundation during the tour. The sizes between the two, we soon found out, were incomparable.

As the tour group moved to the main dome where the Great Refractor is housed, it was clear that this bright blue telescope dominated the room. The size of a school bus, it is still functional 130 years on, along with the 120-ton dome overhead.

With such a large telescope came complications, such as how far away the eyepiece was from the ground. The solution to creating a comfortable observing position wherever the telescope was pointed was a mechanism that turned the floor surrounding the telescope into a giant elevator. When I visited it was daytime, but the observatory does offer visitor options to search the cosmos with it at night.

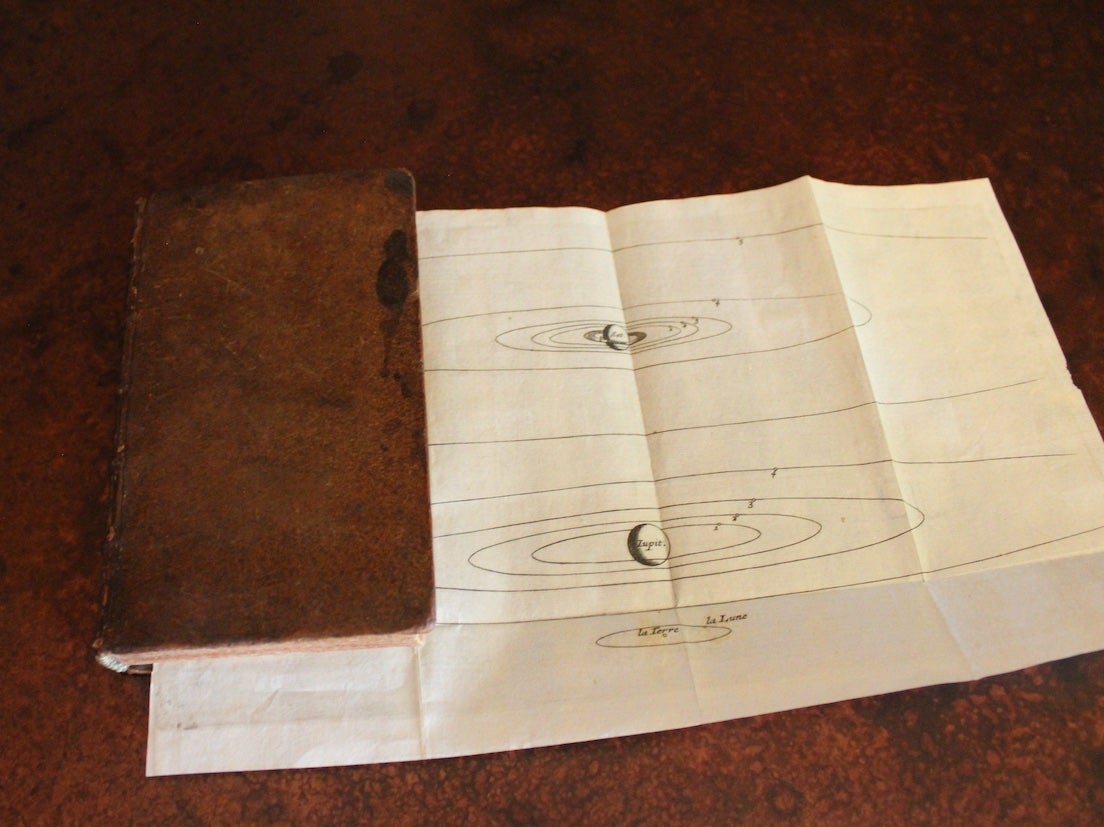

Telescopes are not the only pieces of equipment the observatory continues to hold onto. In one room you can find a collection of early desktop computers, and in another room in the basement, you’ll encounter several large pieces of engineering equipment used to troubleshoot and fabricate the necessary observing tools. In another room still was a collection of astronomy books, vintage binoculars, art, and an old, fat-tire bike used on trips studying the sky in Antarctica. Kois even laughed about an old George Foreman grill they kept, joking about Hale and his associates making a sandwich on it.

All of these items were kept with the goal of preserving as much as the foundation can to further the observatory’s past.

Switching hands

After the property donation, the Yerkes Future Foundation has continually worked to update several aspects of the building and the surrounding 50 acres of land, of which there have been many. When the foundation took ownership of the property, the floors were brown from layers of unstripped wax, the walls were tinged with cigarette smoke, and even some of the offices had remained untouched for years.

Armed with $23 million in funding, the foundation has commenced an effort to revitalize the site and make it usable for visitors. During the two years between purchasing the property and opening the doors to the facility, updates have included adding solar panels, creating meeting rooms and event spaces, cleaning and organizing 130 years’ worth of items, and installing new bathrooms.

Yerkes Head of Science and Education Amanda Bauer says they have many plans for the next 10 years. With the hopes of acquiring another $17 million in donations, the foundation will renovate the Great Refractor, replacing its brick foundation and repainting it, along with other projects like plate digitization and more student programs.

The foundation keeps the community engaged and raises capital with programs like tours of the facility as well as speakers such as former astronauts, and visitor opportunities to use the telescopes. One of the more unique aspects of their revitalization effort includes incorporating art into the fabric of the observatory. High contrast photos of broken glass plates line the hallways, while sculptors, painters, and musicians have all done residency programs that blend the concept of science with art.

Despite the now heavily light polluted location, Yerkes Observatory retains great value. The historic architecture, the research, and the community programs all bring visitors a great sense of pride. Yerkes has traveled from being an observatory without a home to a home for the past, present and future of astronomy.

To learn more about the programs the foundation offers, or if you would like to donate, visit: https://yerkesobservatory.org/.