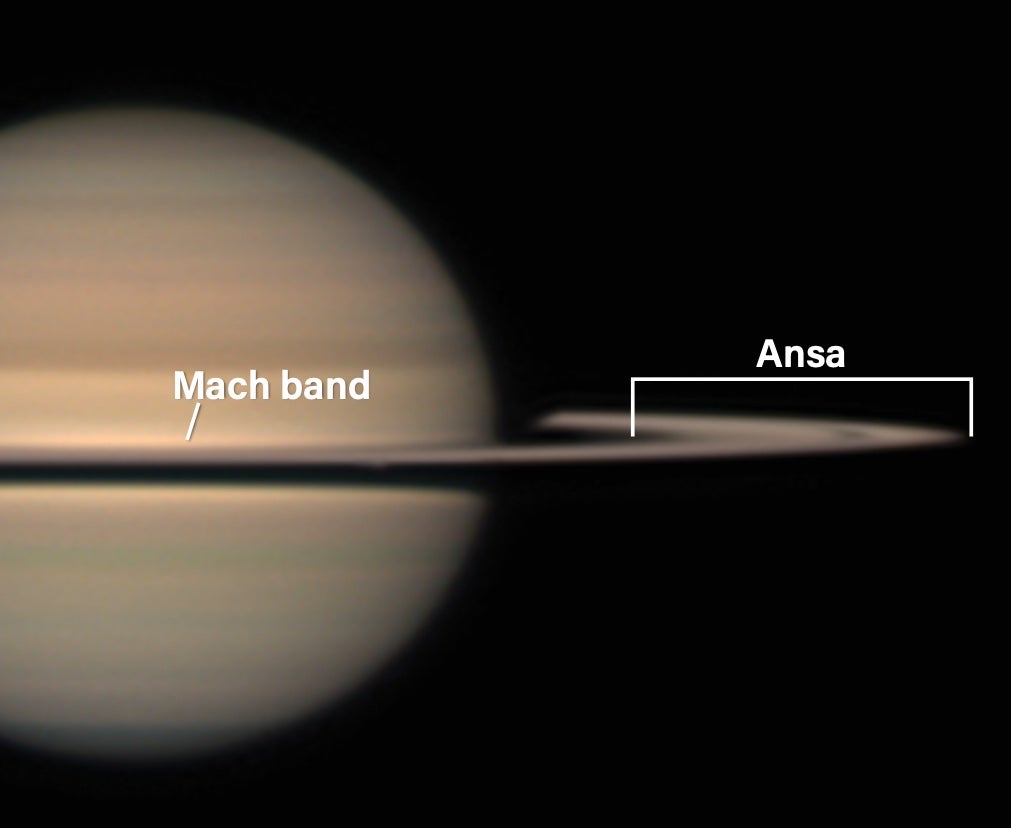

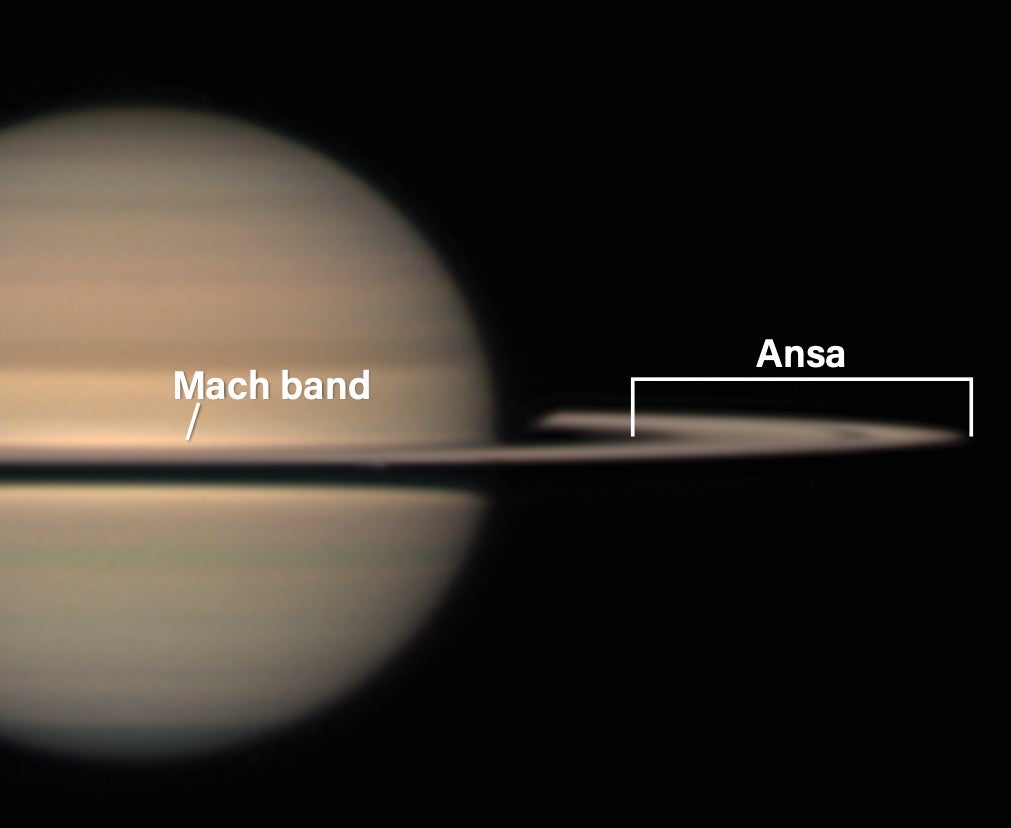

A photo-illustration of the optical illusion known as Mach bands, as seen on Saturn. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly after Ethan Chappel

Roughly every 15 years, Earth passes through the plane of Saturn’s rings, causing them to nearly disappear from view — not to mention generating a variety of other interesting phenomena. The next such edge-on appearance will be in March 2025, though Saturn will unfortunately be too close to the Sun (only 9.5° away) for us to enjoy it.

This year, though, the rings narrowed to a minimum on June 25, tilted just 1.9° from edge-on. This is when I found a fascinating optical phenomenon at play — one that might make you think twice as to whether what you are seeing is real.

On the morning of June 9, I was showing my wife, Deborah Carter, Saturn in bright twilight through my 3-inch Tele Vue refractor. As I described the planet and the near-edge-on appearance of the rings (2.0°), she picked out several features, including the narrow rings on either side of the planet, the shadow of the planet on the rings, and vice versa. However, neither of us could see the rings passing in front of the globe.

After a prolonged study of the ring’s shadow with direct vision, I averted my gaze toward one of the rings’ ansae — the bright “handles” that appear on either side of Saturn where the rings arc around the planet. Suddenly and fleetingly, I saw what appeared to be the full extent of the rings cutting across the face of the planet. They appeared bright against the planet’s equatorial belt and hugged the northern edge of the ring’s shadow — although I was suspicious.

At and near the center of the planet, the rings appear highly foreshortened, appearing much thinner than they do at the ansae. Furthermore, ring-particle shadowing effects make that projected section of the ring appear darker at center than they do at the ansae. What I saw had to be an illusion.

Indeed, I later recalled an observation made by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard. On Oct. 26, 1891, Barnard used the 12-inch refractor at Lick Observatory to study Saturn when the rings were tilted only 1.6° from edge-on. Even with magnifications of 150x, 175x, and 500x, he reported the rings were invisible. He was struck, however, by an important visual effect: “Looking at the black trace on the ball, and then glancing at the sky near the sides of the planet, I could, apparently, see the rings for a moment as a faint line of light on the dark sky. I satisfied myself beyond question that this was an optical phenomenon.”

Barnard believed the faint line of light was an afterimage of the ring’s shadow. “I mention this,” he wrote, “as it might some time mislead an observer, who would think he had glimpsed the real ring. Perhaps this same phenomenon has a bearing on other kinds of astronomical observations.”

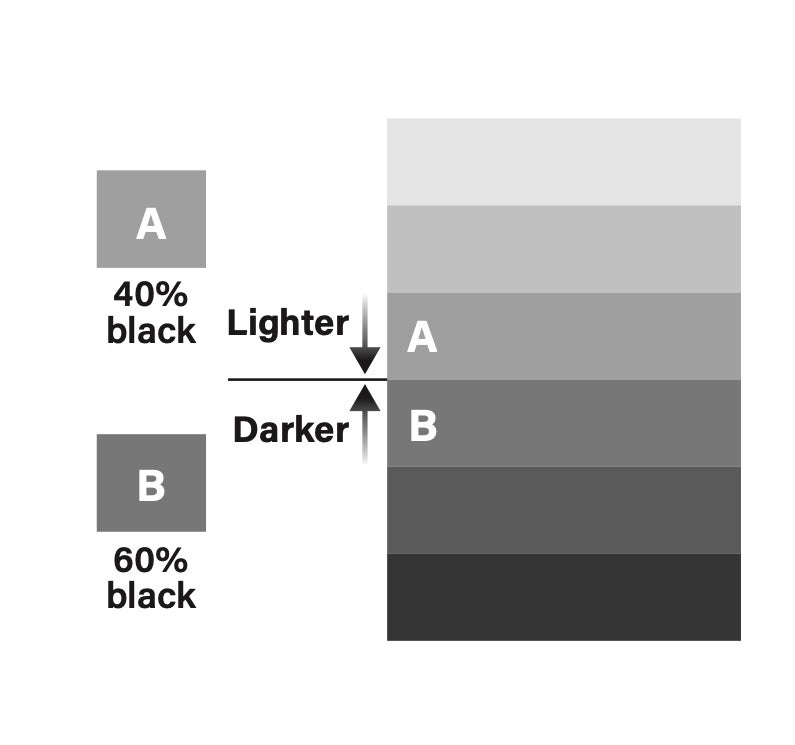

With these words in mind, I observed Saturn again on the mornings of June 18 and 19, following the planet well into twilight. While my observation and Barnard’s were different, both dealt with the ring’s shadow. After staring at the ring’s shadow for a prolonged period of time and then averting my gaze to the side of the planet, I could create a similar, albeit fleeting, optical illusion that exaggerates the edge of the bright equatorial zone next to the ring’s shadow. This phenomenon is known as a Mach band, or the Mach effect. It’s an optical illusion where the edge of a bright object next to a dark object appears even lighter, and vice versa.

One can also see Saturn’s rings projected a short way across the face of the planet, where they taper like pincers. I found that the best time to see this ring aspect is during bright twilight when contrast between the planet and the sky is at its lowest. I call it “ghosting” because the appearance through a small telescope looks like a ghostly apparition.

Saturn’s rings opened from about 2° in June of this year to between 4.5° and 5° in October. So it should now be possible to resolve Saturn’s ring across the planet under sufficient magnification and excellent seeing conditions. This gives us a splendid opportunity to observe the visual aspect of the narrowly opened ring before it starts to close by the beginning of December. By the time we lose Saturn to the Sun’s glare in February 2025, the rings will be less than 3° from edge-on. I’ll be most interested in knowing what you see or don’t see before this time. The real challenge will start when Saturn reemerges into the morning twilight in early May 2025 and the rings will be opening to 2° again.

Be sure to send observations with time and date, telescope used, magnifications, and the state of the atmosphere to sjomeara31@gmail.com.