Now Reading: 10 most powerful solar flares of 2024

-

01

10 most powerful solar flares of 2024

10 most powerful solar flares of 2024

It’s been a busy year on the sun, as it officially entered the peak of its roughly 11-year cycle of activity, known as solar maximum. In 2024, the sun launched over 50 X-class solar flares — the most powerful type of solar flare — at Earth.

Solar flares are categorized by the level of X-rays they produce in a specific wavelength range (1 to 8 angstroms). Solar flare classes follow a logarithmic scale, with each flare class — C, M and X — 10 times stronger than the previous one. Solar flares can also unleash giant clouds of plasma known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which can cause geomagnetic storms and widespread auroras.

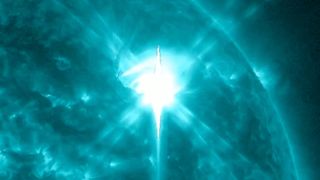

The video above shows observations from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA). The left panels show emissions from AIA 131 Å, and the right from AIA 171 Å. These reveal plasma at approximately 18 million and 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (10 million and 1 million degrees Celsius), respectively. Below, we take a look at the 10 strongest solar flares between Jan. 1 and Dec. 10, 2024.

10. X3.38 — Feb. 9

This X3.38 flare, which occurred over the southwestern edge of the sun, would have measured much higher if most of the emission had not been blocked by the edge of the sun. This flare shows a good example of a “coronal wave,” as coronal material in AIA 171 Å emission is seen to be almost “blown out of the way” by the original flare.

During this massive flare on Feb. 9, as with almost all X-class flares, the bright and concentrated signal produced an “X” or “star” shape diffraction pattern, which emanated from the bright flare site in AIA 131 Å emission. This diffraction pattern is an artifact of the telescope camera; it did not actually occur on the sun.

9. X3.48 — May 15

Related stories:

This is the first of four solar flares on this list to have originated from solar active region AR 13664.

AR 13664 was a famous highly productive active region, producing 12 X-class solar flares in just six days. The May 15 flare was the final X-class flare visible from Earth, and it would have measured higher if it had not already been partly obscured by the western edge of the sun.

As the active region rotated around the back of the sun and reemerged into view two weeks later, it continued to produce large flares (under a new active region number). Observations from the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter also revealed large flares from the region during the period it was hidden from Earth’s view.

8. X3.98 — May 10

This solar flare also originated from active region AR 13664. The flare produced a strong Earth-directed CME — one of several to launch within a 48-hour window. The CME erupted from the perfect location on the sun to cause maximum impact on Earth.

As the series of CMEs arrived at our planet on May 11-12, they produced a G5 geomagnetic storm — the strongest geomagnetic storm since 2003. This resulted in widespread auroras at low latitudes that were viewed by millions across the world.

7. X4.52 – May 6

Another flare earlier in May was launched from active region AR 13663 — one active region lower than the source of the two flares above. While AR 13664 was busy producing eruptive flares in the sun’s southern hemisphere, AR 13663 unleashed a series of X-class solar flares from the northern hemisphere. Most of these flares, including this May 6 event, did not produce notable Earth-directed coronal mass ejections.

6. X4.54 — Sept. 14

This solar flare produced a strong CME, directed over the sun’s eastern limb. For flares around this magnitude and above, you can notice the pixel saturation overflowing into neighboring pixels and producing periodic sharp and jagged saturation features that bleed out above and below the bright flare site.

5. X5.89 — May 11

Just like the flare on May 6, this event originated in AR 13664. This flare also produced a coronal mass ejection, which formed part of the chain of CMEs that contributed to the extreme and long-duration G5 geomagnetic storm aimed at Earth.

Because the May 11 flare occurred closer to the limb than the earlier flare from the same active region, it was slightly less optimally placed to impact us head-on.

4. X6.37 – Feb. 22

Not all strong solar flares are interesting. Although this one clocked in at X6.37, it did not produce any Earth-directed CMEs and was not particularly noteworthy.

3. X7.10 — Oct. 1

This flare is one of two on this list to originate from active region AR 13842, alongside the strongest flare on the list.

Neither of the two strongest flares from this active region directed strong geomagnetic storms at Earth. However, smaller X-class flares from this same active region later went on to release the CMEs responsible for a strong G4 geomagnetic storm on Oct. 10, which again caused widespread low-latitude auroras across the world.

This is a good lesson to remember: Solar flare size is only weakly correlated with the potential for a flare-induced CME to create strong auroras. In the case of this active region, the larger flares had a smaller geomagnetic impact than the smaller flares did.

2. X8.79 — May 14

This is the fourth and final flare on this list from active region AR 13664, which has been by far the most X-class-productive active region during this solar cycle (so far). However, unlike the previous flares to erupt from this region, the May 14 flare was confined, without a significant eruption. Because of this, the physical size of the flare appears small, despite the strong X-ray emission.

1. X9.0 — Oct. 3

Finally, the largest flare of the year so far produced an enormous amount of energy — nine times the amount needed to cross the X-class-flare threshold. This was the third-largest solar flare since 2011 and the fifth-largest since 2005.

Will this be the strongest solar flare we see in Solar Cycle 25? As solar maximum continues into 2025, we’ll have to wait and see.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly