Now Reading: 2026 Outlook: Can Acquisition Reform Deliver for Military Space?

-

01

2026 Outlook: Can Acquisition Reform Deliver for Military Space?

2026 Outlook: Can Acquisition Reform Deliver for Military Space?

The United States military space enterprise enters 2026 under pressure to turn long-promised acquisition reforms into results. For defense space companies, the year is shaping up as a test of whether commercial integration translates into lasting capability.

After years of encouraging private investment and experimentation, Pentagon leaders now face harder questions about what becomes part of the standing architecture. The rhetoric around “commercial first” has been familiar for decades. In 2026, the pressure to make it operational will be harder to avoid.

From slogans to structure

At the center of the shift is a reworking of how the Space Force buys capability. Secretary of the Air Force Troy Meink described the current push as a “generational opportunity” to improve acquisition, and 2026 is when those changes are expected to start improving how programs are organized and funded.

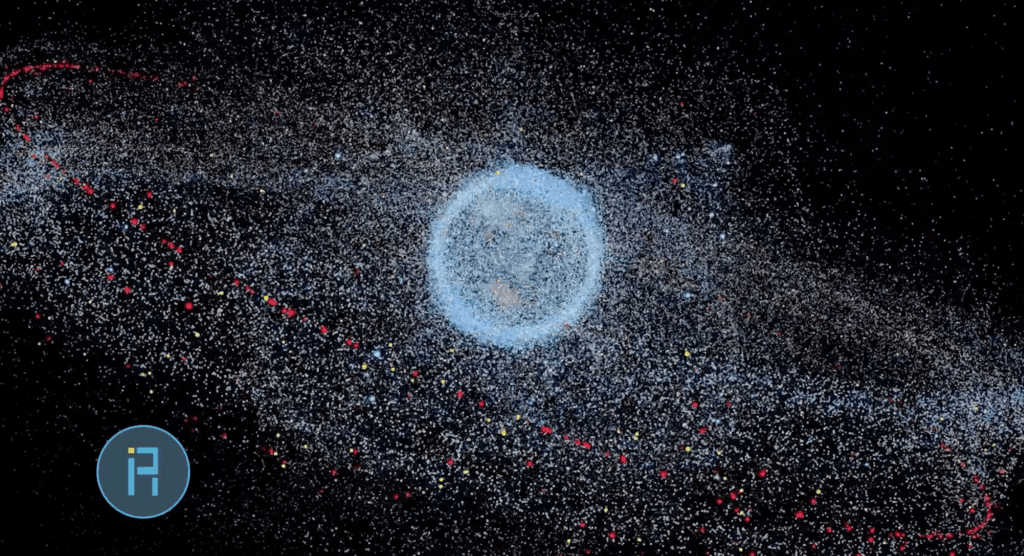

One potentially consequential change is the move away from platform-centric programs toward mission portfolios. Instead of managing missile warning satellites, ground systems or electronic warfare payloads as separate line items, the Space Force would group them into integrated capability packages with portfolio acquisition executives holding more authority to set requirements and move money. Missile warning, space domain awareness and communications are among the areas expected to be handled this way.

The logic is straightforward. Space programs have long struggled with rigid requirements, duplicative efforts and an inability to trade cost, schedule and performance across systems that are meant to work together. Portfolio management is intended to give acquisition leaders more flexibility and to shorten the timeline between operational needs and buying decisions.

The risk is that reorganization consumes time and attention without changing outcomes. Both Meink and acting service acquisition executive Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy have cautioned that the shift is not meant to add layers or dramatically upend structures that already lean toward a portfolio view.

What industry will watch in 2026 is less the org chart and more the behavior. Does authority actually move down to portfolio executives and program managers? Do requirements loosen enough to allow commercial systems to be adopted without expensive customization? And does the Pentagon finally close the loop between demonstration and fielding?

That last point has been a persistent issue in military space procurement. New guidance the Pentagon released in November emphasizes capability delivery over endless prototyping, but history has made companies skeptical.

Lt. Gen. Philip Garrant, who runs Space Systems Command, has mentioned workforce development as part of the fix, arguing that program managers need different skills in an environment that prioritizes speed and commercial integration. Whether that cultural shift takes hold is still an open question.

Commercial, but at scale?

The Space Force enters 2026 with what Purdy has called an “embarrassment of riches” in commercial space offerings. Imaging, radio-frequency sensing, data transport and autonomy tools are no longer speculative. The question is whether the Pentagon makes them programs of record or keeps them walled off in small pilot efforts.

Congress has long pushed for integration of commercial space technologies. Bill Adkins, professional staff member of the House Appropriations defense subcommittee, noted that using commercial technology has been official policy for decades, yet budgets dedicated to it remain thin. Speaking at the Baird Defense conference, he pointed to national security launch as an example of where the government successfully structured a market around commercial providers, and to space domain awareness as an area where it has not, despite clear gaps and active private investment.

Adkins suggested that isolating commercial efforts in separate offices signals that they are optional. Integrating commercial services into major programs forces tradeoffs but also normalizes their use. The portfolio approach could help, if portfolio managers are incentivized to buy outcomes rather than hardware.

Another inflection point is the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program and its follow-on vehicles, which have been a key bridge from prototype to operations for space companies. The lapse in SBIR authorization heading into 2026 has injected uncertainty into a pipeline that venture investors increasingly view as a signal of government interest. Purdy has warned that losing that feeder would undercut the very dual-use ecosystem the Pentagon says it wants to leverage.

Layered on top is the perennial budget problem. Continuing resolutions and shutdowns do not just slow Pentagon execution; they strain smaller commercial firms that rely on predictable cash flow. Unreliable budgets, executives point out, make it harder for industry to deliver on the speed the military now demands.

Golden Dome’s first test

Few programs embody the ambition and ambiguity of the current moment like Golden Dome, the administration’s missile defense initiative. By 2026, it remains a sprawling concept with political momentum and limited public definition, but it is also absorbing investment from primes and venture-backed firms betting that pieces of it will become programs of record.

For industry, the opportunity comes with risk. Gen. Michael Guetlein, program manager of Golden Dome, has set an initial operational capability target of summer 2028, with 2026 focused on prototypes, industry engagement and foundational command-and-control work. Congressional proposals to require regular reporting on architecture, cost and testing suggest lawmakers want tighter oversight as spending ramps.

Golden Dome is also an early proving ground for the Pentagon’s acquisition reforms. If leaders are serious about pulling commercial technology into national security programs faster, this is where it should show. If the effort devolves into bespoke designs and long development cycles, it will reinforce skepticism that reform has real teeth.

Satellite servicing and the money question

Beyond missile defense, 2026 could be decisive for a quieter but strategically important sector: in-space servicing, maneuver and logistics. The technology is maturing. What remains unclear is who will pay at scale.

The Space Force’s planned on-orbit refueling demonstrations in geostationary orbit are the most concrete signal yet that the military is taking the idea seriously. Astroscale’s Provisioner spacecraft is slated to refuel a Space Force satellite and then draw propellant from an Orbit Fab depot to attempt a second transfer, effectively testing a rudimentary fuel supply chain in space. Parallel efforts, including Northrop Grumman’s Elixir program, aim to prove rendezvous and docking capabilities.

For planners, the demos address a fundamental debate. As launch costs fall and satellite manufacturing gets cheaper, is it more efficient to replace spacecraft or to invest in infrastructure that extends their lives and enables maneuver? Space Force leaders argue that the question misses the strategic point. Launch gets capability into orbit. Logistics determines how that capability survives and adapts under pressure.

Col. James Horne, commander of the launch range at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, has framed it bluntly: The Space Force cannot defend or reposition satellites if those spacecraft cannot maneuver. Dynamic space operations, a phrase increasingly used by the service, depend on mobility and sustainment that rockets alone cannot provide.

What 2026 is unlikely to deliver is a full commitment. Purdy has acknowledged that specific funding for large-scale logistics infrastructure is not yet in place. The coming year will be about evidence. If the refueling demonstrations work and align with operational concepts, they strengthen the case for making space logistics a core mission. If not, servicing risks remaining a niche capability, overshadowed by cheaper launch and rapid reconstitution.

A narrower window for excuses

For the national security space industry, 2026 looks like a narrowing window. The Pentagon has new acquisition authorities, clearer policy guidance and a threat environment that leaves less room for delay. Commercial technology is no longer novel, and neither are the arguments for using it.

What remains uncertain is execution. Portfolio management, commercial-first buying and ambitious programs like Golden Dome all depend on follow-through in budgets, contracts and requirements. By the end of 2026, industry should have a better sense of whether the Space Force’s reform moment is real or whether it joins the long list of well-intentioned efforts that changed processes without changing outcomes.

This article first appeared in the January 2026 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors