Now Reading: Is astronomy safe from organized scientific fraud?

-

01

Is astronomy safe from organized scientific fraud?

Is astronomy safe from organized scientific fraud?

Astronomy and space sciences have mostly avoided the fraudulent practices of paper mills and predatory journals, but that might be about to change, warn the authors of a new report that delves into the ugly machinations of criminal organizations that profit from fake science.

“Because space is a huge economic priority and many countries are doubling down on space research, I would expect to see the fraudulent publishing industry expand into this area,” the lead author of the report, Reese Richardson from Northwestern University, told Space.com.

Worryingly, the report concludes that fraudulent science publishing is starting to outpace legitimate journals, saying that if nothing is done about this issue, it could forever pollute a wealth of scientific literature and even result in artificial intelligence (AI) being trained on made-up data.

One of the prime means of assessing a scientist’s career is considering what papers they’ve been involved with: How many papers have them as first author? How many as a co-author? How many cite their work?

However, this metric appears to pave the way for some manipulative tactics. Paper mills and predatory journals prey on researchers by creating made-up papers, which are often plagiarized, full of nonsense science or describe developments so minor or low quality as to not even justify publication. They sometimes even offer authorship to researchers for prices amounting to hundreds or even thousands of dollars. A paper can also be pushed through a scam peer-review process for a price to make sure it gets published in a fraudulent journal.

Ultimately, the criminal organizations at the heart of this nefarious industry make millions out of scientific fraud. Sometimes the journals these fake research papers are published in are created for that monetary purpose.

Other times, though, a legitimate journal can be hijacked. The newly published report on academic fraud, for instance, cites the example of the British journal HIV Nursing. It had ceased publication — only for its domain name to be bought by a criminal organization so that a fake journal in its name could be created with the sole intent of publishing fraudulent papers from a paper mill, often on topics that had nothing to do with HIV or nursing. The most extreme cases involve these organizations infiltrating a legitimate journal, buying off staff to ease fraudulent papers through to publication.

“Paper mills tend to prefer topics that are more easily exploitable,” says Richardson. “For instance, there’s a lot of suspected paper mill activity in materials science.”

In other words, if there is profit to be gained from a field such as materials sciences, medical sciences or engineering, then that makes the field vulnerable to fraudulent publications. Richardson cites the example of solar panel technology as a case in point.

“One of the heavily exploited areas by paper mills is renewable energy,” he said, highlighting examples of dozens of papers in this field where he found the same curves on graphs just repeated over and over, in different papers or sometimes even in the same paper, in both fraudulent publications and legitimate journals from well-regarded North American and European publishers.

These copy and paste jobs are indicative of a problem that in this particular topic can hamper real research into renewable energy technology that could help us to combat the climate crisis.

Yet, “Space and astronomy research is one of the areas where not a lot of paper mill activity has been detected,” said Richardson.

There could be several reasons for this. One is that those who seek out suspected paper mills tend to come from the scientific fields most affected by this plague of fake papers, and so they are not sufficiently familiar with astronomical subjects to recognize the fake ones.

“If there is significant paper mill activity in space and astronomical research, then it’s possible that it just hasn’t really been detected,” said Richardson.

Another possibility is that space and astronomy isn’t a particularly easy subject to exploit for profit. However, this could be about to change. In many developing countries where paper mills are particularly rife, the space industry is beginning to grow. This could soon begin to attract the criminal organizations looking for exploitable areas of science.

To prevent this and to curtail the activities of paper mills, the report concludes that not only does there need to be greater scrutiny on journal editorial processes, but we also need smarter methods of identifying fake papers and, most revolutionary of all, a major rethink about how the scientific community incentivizes science as a career.

Time is of the essence. “At some point it will be too late and scientific literature will become completely poisoned,” said a co-author of the report, Luís Amaral of Northwestern University, in a statement. “We need to be aware of the seriousness of this problem and take measures to address it.”

The problem could also be about to grow far worse. There are already debates about legitimate scientific papers utilizing artificial intelligence, and now AI can be used by paper mills to spit out fake science ever faster. If those fraudulent papers lay undetected in the scientific literature, then they will inevitably be used to train future generations of AI, infecting them with fake scientific data that the AI will think is real, leading to AI giving bad results — not just in generative chat apps, but also when applied to building complex climate simulations, seeking cures for diseases or modeling difficult problems.

The fraudsters are poisoning the well for profit and if they’re not stopped soon, then the days of being able to trust the body of scientific literature, and of having the ability to distinguish between scientific fact and scientific fake, may be coming to an end.

The report was published on Aug. 4 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

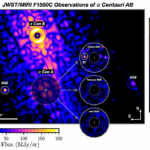

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits