Now Reading: The future of space infrastructure

-

01

The future of space infrastructure

The future of space infrastructure

In this week’s episode of Space Minds, host David Ariosto speaks with Al Tadros, Chief Technology Officer at Redwire, to explore the future of space infrastructure and commercialization.

From the growing role of private investment in orbit to breakthroughs in bioprinting and pharmaceuticals in microgravity, Tadros explains why this is one of the most exciting times in the history of space.

He also discusses the balance between civil, commercial, and national security missions, and how companies like Redwire are shaping the new economy beyond Earth. With decades of experience at the forefront of satellite and space systems, Tadros offers a unique perspective on where the industry is heading—and why the next era of exploration could be even more transformative than the Apollo years.

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Time Markers

00:00 – Episode introduction

00:27 – Welcome

00:55 – What is space infrastructure?

03:19 – The cost to access space

06:05 – Consolidation effect

09:04 – Evolution of software

11:48 – Bioprinting

14:04 – Space to space economy

16:00 – Balancing civil, commercial and national security

20:01 – New space norms

24:34 – Al’s space journey

Transcript – Al Tadros Conversation

David Ariosto – Thank you. All right. All right, I think we’ll just jump right into it to be to be honest, if that’s okay with you. Al Absolutely. All right. Al tedro No. Sorry, I said Tedros. Tedros, right. Tedros, yep. Al tedro Okay. Al Tadros, the Chief Technology Officer at Redwire, it is a pleasure to have you on the show.

Al Tadros – Great. Thanks. David, pleasure to be here.

David Ariosto – Yeah, so your at Redwire is sort of across the board in terms of tech development and commercialization and just sort of like, you know, the nature of a technical culture that that you’re, you’re building there in this, you know, this relatively new commercial era that we’ve all seen, I say relatively because we’re a decade or two plus here, but I’m just kind of curious when it comes to Redwire, one of your previous roles was chief growth Officer and Executive Vice President of Space infrastructure, right? And you did something really similar with Maxar in terms of your role as. Vice President of infrastructure and civil space technologies. And I think that’s a really good starting point for this conversation, because when we talk about space infrastructure, what, what exactly are we referring to?

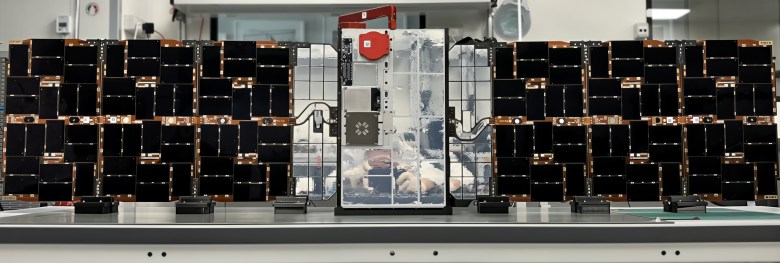

Al Tadros – Right. Great question. And first, I mean, I think it’s one of the most exciting, if not the most exciting time ever in the space industry, and I’ll explain a little bit why and how that relates to the space infrastructure. So a lot of the history in space has been large primes. You know, companies can take on significant role, and oftentimes owns a whole mission area. You know, they will own, you know, missile warning and so forth. The thing about space industry is that, you know, there’s so much technology and so many subsystems and capabilities that that exist that one company can’t be the expert and cost effective on everything at once. So space infrastructure is a lot of the capabilities that go into a mission, whether it’s propulsion and structure, avionics, power systems and solar rates.

There’s a lot of components, subsystems and technologies that go into missions, but those can be applied to different missions. So that’s what Redwire really was formed around the acquisition and integration of capabilities that provide infrastructure, the subsystems, the platforms, the manufacturing capability, the scaling for, you know, multiple missions, and not just one specific weather or comms or missile warning or and so forth. So that’s what Redwire was really formed. And it’s a great introduction that you gave. One of the roles that I had in the pleasure of is, is the, you know, supporting the M and A that Redwire used. So it isn’t just the technologies or just the capabilities that we put together, but it is through an M and A that we that we are growing that capability and scaling it. And that’s one of the pleasures of my new role at Redwire. That was in addition to what I had done before in my prior roles.

David Ariosto – Yeah. So, you know, I think, taking a step back, and kind of, when you look at, sort of the broader industry, space has always been sort of the purview of government, nation states. And, you know, when you look at the space race, this was, this was NASA versus, you know, the the old Soviet program that later sort of developed into Roscosmos and other factors. And you still have that to some extent, with sort of the Chinese aspect of this. And that seems to be part of the geopolitical factors driving a lot of this. But at the same time, you know, what I find most interesting about Redwire, and accompanies like Redwire, is you’re looking for things that aren’t necessarily taxpayer funded, in terms of the pharmaceutical developments and orbital services and just the nature of this, I’ve heard almost described as this, like new factory floor in lower orbit. And I wonder if you can kind of unpack that a little bit for me.

Al Tadros – Yeah. Well, like I said, it’s some of the most exciting times for good reason. First of all, access to space. I mean, as you said, it used space used to be the purview of governments, and that was largely because just access to space was so rare and so expensive. And you know, the launch vehicles were not nation owned launch vehicles, more recently, the cost of launch, the frequency of launch, the access, you know, it became almost like a consumer acquireable capability, right? A high net worth individual and a beast and a startup could go off and buy, you know, a slot on a launch vehicle…

David Ariosto – …nonprofit or university, or, you know, anything…

Al Tadros – So all of a sudden it opens up to what, what’s the realm of the possible here, from the economics perspective, and VC didn’t have to guess whether they, you know, they can fund somebody to go to space. You know, they knew that there was going to be a transporter mission or electron, you know, going up, and they can buy it, and they knew the price, you know, commercially set prices and the frequency and so forth. So that really opened up the economy for for, you know, private investors and you know, companies to consider going into markets like that.

In fact, I was just talking to our team about a researcher in Economics Department at Oxford University who is studying just generally, early stage markets. And he started looking at space, you know, in the early stage markets, of space, free markets, not government funded. So there’s even, you know, a broader research kind of community looking at these markets and how they’re evolving, and how they can be spurred on by government co investment, but by private investment as well. So it’s, it’s a exciting time from that perspective, for sure.

David Ariosto – I wonder though that in that context, yes, you see like this explosion of commercial technologies and explosion of new companies that. Entering the space and, you know, individuals and nonprofits and universities, but at the same time, there seems to be this sort of, sort of like space 2.0 commercial sector that’s kind of developing here in terms of the consolidation effect, right? Like you have some of these major players who have gotten the real estate that they want already, which is kind of a wild kind of concept in the sense that this is no longer really new. And so that consolidating factor, I wonder how that plays into sort of broader strategy for Redwire, but also sort of the nature of competitiveness when it comes to low Earth orbit. And some of these, you know, some of these new exploratory realms, like cislunar space and even the lunar services market.

Al Tadros – So as you’ve mentioned earlier, part of my background was many years at Space Systems Loral or Maxar, and the focus there was actually what I consider some of the original commercial space, which is geo communication satellites. And by commercial, I literally mean these are, you know, private companies, you know, publicly traded companies that generate revenue off of communications services, subscriptions to enterprise users, individual users, that fed into buying new satellites, new launch vehicles, ground systems, you know, and and services. So that whole economy is where I kind of grew into…

David Ariosto – …and those are your roots, in a way.

Al Tadros – Yeah, no, you understand very clearly the pragmatic nature of it, the regulatory, the insurance, the operations cost, the, you know, the color of money that that is very different from the how the government does things with taxpayer funded activity. So I bring that into my thinking and our thinking at Redwire, with regards to the pragmatism of someone wanting to, you know, the popular term here in Silicon Valley where I live is disrupt this and disrupt that.

Well, you know, there’s a lot of details in history and people trying to do that, and understanding those nuances is really important if you want to be a successful and a sustainable business, not just the cool technologies, which there are plenty of, and the cool pictures of rockets lighting up, which is the plenty of it’s a real pragmatic business aspects that that matter. And so yes, there is more access to space now and there are more opportunities for investors. But then there’s the real detailed business, you know, aspects of running a company regardless that we have to understand and consider and and work in, in parallel with all the other cool space stuff that we do. And I think that’s one of the things that Redwire really does well, is is is think about things from a business perspective, like, like you mentioned, and be thoughtful about, how do we sustain our business, not just, you know, how do we push technologies or push the envelope on on different capabilities?

David Ariosto – Well, you mentioned Silicon Valley and I think this is like a natural segue in terms of this conversation, because when you look at the space industry, you see a lot of the heads of major space companies, Elon Musk, SpaceX, Jeff Bezos, you know, and with, with Blue Origin, Eric Schmidt, you know, now at relativity, these are all individuals who had a software background in some of some capacities, right? And so there’s, it’s almost like there’s, there’s this nexus and this convergence that we actually did see during the Apollo era. And it’s kind of coming around again. And I guess I wonder, in that context, this iteration of the the industry, in terms of developing that factory floor, that infrastructure that we’re talking about, where is that balance between the software and the hardware?

Now, because, you know, we’re talking about, we’re talking about orbital data on orbit, just taking advantage of sort of that, those natural cooling sinks and, you know, constant power of the sun. We’re talking about sort of orbital services, talking about storage, you know, all these things that that might have been sort of terrestrial concerns, or start migrating a bit into space. And I just, I wonder, for a company like Redwire. How you kind of think about that in terms of traditional hardware, which has been associated with infrastructure in space in the past, and this, this evolution with software?

Al Tadros – Yeah. So first of all, I think it’s always been. I mean, I’ve been in the industry 35 years, and going back to the original kind of cell phone industry, the Craig macaws of the industry and so forth. It’s always been a desire to, you know, expand the markets, the terrestrial markets, by using space capabilities. I mentioned space satellite communications. I mean, that was one of the earliest commercialization of space capabilities and GEO satellites, but also things like ICO (Global), Teledesic, Globalstar and Iridium, those were the original throws of of, how can we expand it?

And it’s been some of the, you know, the high net worth individuals and and large successes. So it continues to be a real interest and focus for. Of Redwire to partner with terrestrial industries, whether it’s pharmaceuticals or biotech, telecom, you know, even war fighters, to not have space as a unique, exquisite domain, but as part of that ecosystem. So thinking of biomed as you know, space is one aspect of it, not the focal point. And what do in microgravity to augment your research, you know, on for, for, you know, bioprinting or crystal growth, for pharmaceuticals.

David Ariosto – The bioprinting aspect I find is just wild. I really do. I think, I think that is such a, such a neat kind of aspect of all this in terms of what you space and how these things, these lattices, kind of develop in ways that sort of mimic, you know, processes within the human body that you just can’t do terrestrially. It just that that that, to me, strikes me as a as an opportunity where there’s a market that already exists. You’re not like creating new markets.

Al Tadros – But yeah, exactly, and that’s the case in all of these. There’s already billions of dollars being invested in pharmaceuticals for crystal growth and and for medication, you know, research, so And yes, what we want to do is be part of that, not create, you know, some unique, you know, space unique kind of thing. What Redwire does is facilitated. It is different to operate in space. First of all, you have to survive launch. People think about, you know, space as being this light touch, free floating, Zero-G…

David Ariosto – …modeling effect of getting up there.

Al Tadros – Yeah, it’s pretty jarring, acoustics, vibration, vacuum, something, you know, if you’re going into the vacuum of space. So there’s a lot of engineering technology to survive launch and then to operate in space, and then if you’re going to recover, the re entry and landing, and then recovery. So there’s a lot of elements there that we work with terrestrial industries like I mentioned, to expand their research envelope and be able to consider, then microgravity as part of the envelope of research. And yes, just thinking scientists, I mean, of course, naturally have lived in 1g their research has been in 1g buoyancy has been affected by 1g thermal. And, you know, everything has been 1g so this adds a whole new dimension to not look possible. And like you said, bioprinting in microgravity, all of a sudden, you don’t need scaffolding. You don’t need stiffeners. You don’t need to think about, okay, how do I make a 3d structure like that, all of a sudden, you know, the lack of gravity helps you at least solve that problem. And then we Redwire are are working to, you know, address all the other challenges that that take get you to space.

David Ariosto – Producing it seems like the low hanging fruit. It’s getting its market at, at a level that that is still sort of a bottom line positive type of approach that, to me, is, is the tricky aspect of this. Because, I mean, there’s all this talk about helium three on the moon, there’s all this talk about all these resources that are in space. But, you know, until you have a sort of a true space for space economy, getting that to market and the US, I mean, it’s, it’s cheaper. Now, no question, but it’s, it’s not that cheap.

Al Tadros – No, no, it isn’t. And, yeah, I mean, I’m, you know, it’s just a matter of time horizons. Sure, cheaper, but if you’re looking at investing in the next two to three years for a return, you might not want to. You know, depend on resource return from the lunar surface. LEO, you do start to see some potential to have regular up, mass and down mass launch and recovery materials. And some of the markets, like crystal growth, which we’ve done and talked quite a bit about, you don’t need to bring a whole lot back.

The seed crystals for pharmaceuticals are sufficient to actually start a whole line of of new medications, and we’ve already demonstrated that so, so those are some of the, probably the, some of the earliest, you know, successes that we’ll see is things like, you know, bioprinting and pharmaceuticals one time, up and back kind of activities. But yes, look, I lived most of my career where launches of, you know, maybe 10 a year was just outstanding. And we’re launching, you know, 100, 200 times a year. So up mass and down mass already is unbelievably, you know, increased tempo. And hence, I think that the economic viability is near term for a lot of what we’re looking at.

David Ariosto – You know, I think it to that point. I think it’s telling so I’ve had some some colleagues who are photographers that that work, you know, as freelancers for NASA. And they used to be at every. Launch covering every single one multiple angles, and the majority of them they don’t even cover now. They don’t even just shoot, because it’s just so, so frequent. I won’t say it’s, you know, it’s a level of commercial, commercial air travel yet, but I mean, that seems to be far away. I know that Mr. Musk has talked about that in some capacities, but you mentioned something earlier that I’d be remiss if I didn’t dig on, dig in on. And it was the nature of war fighters. And it I kind of wonder, in the context of Redwire, how you balance the two? Because clearly that is that is a steady and growing market. Golden Dome is still what everyone seems to be talking about in terms of growth.

It’s somewhat ill defined in terms of the scope of it, but clearly has to do with hypersonic surveillance, tracking, detection, all of these, these things. But you know, for a company like Redwire, how you marry the focus on building infrastructure that serves civil, commercial and national security needs all at once, that sort of dual, dual use structures, and how that presents both opportunities and maybe even challenges. When you’re you’re going overseas, and you’re looking at other markets in terms of developing these things, because it’s, you know, there’s a there’s an I just would imagine there’s a natural symbiosis with a lot of this technology, and there’s a natural growth strategy that’s associated with it. But how you how you scale beyond that, when those concerns of national security sometimes may or may not jive with the international competitors that you’re dealing with?

Al Tadros – So yeah. You know, the space industry, by its nature, has been, you know, grew out of a lot of the Cold War activities has been a government, you know, focus for national kind of dominance, prestige, human space flight, very much the same. You know, the ability to take humans and sustain them in spaces is a symbol of national prestige and capabilities. And so…

David Ariosto – The exercise in some terms of some of this stuff, in terms of, like, whether or not you’re a true space power, you have to, you have to do a certain amount of things, and the Chinese planting, flag on the moon and that sort of thing.

Al Tadros – Yeah, so it is. It isn’t all about national security. Isn’t all about just weapons and and, you know, the defense, it is literally how you behave in space, how you invest in space. It’s an indication of your, you know, your prowess and and, and capability. And, quite frankly, it’s a deterrence at that point, right to to others, you know, being aggressive. So, so that has been a priority for the nation. And like I mentioned earlier, a lot of spaces, just getting to space. So building capabilities, and that’s something that Redwire has a forte in is, you know, understanding the requirements, the environments, the ability to survive launch and survive space environments. So whether it’s a, you know, an optical system for a missile warning, missile tracking system, or, you know, biological experiment. We’re taking up those kind of same engineering skills and can be applied.

But yes, we do have a legacy through through acquisitions and working with the National Defense. And we do have a a history in working with the government on national security missions, and that is one of our by the way, golden dome is, is the name that’s, you know, applied now, most recently, to a lot of capabilities that have been worked on. So for, just for people’s awareness, this isn’t like something new that all of a sudden, you know, is looked at. There are a lot of pieces that the nation has been looking at, including, you know, space based interceptors and missile warning, missile tracking. One of the things that we’re very passionate about is joint domain operations. Space, again, is not isolated and exquisite. It is part of a war fighting capability, combined with air and ground and marine. So we think of it in that way. And we were operating, you know, in that way.

David Ariosto – I wonder though in the context of that right, because we have, we have so many different companies that are starting to operate on orbit. You have, you know, competitors, geopolitical competitors, namely Beijing, to a lesser extent, Russia, and to some extent, North Korea and Iran, even that are sort of exploring space based capabilities. You know, clearly, hypersonics is a big priority for all of those nations. But, but the real teeth of the governing structure was, it was a treaty that was signed two years before the Apollo moon landing in (19)67 right? And so it seems that, you know, there, there have been other other trees over the course of the years, but, but that’s the big one, the Outer Space Treaty of (19)67 right?

And I, I’ve heard it described by by those that the commercial sector is actually maybe an arena that can start to sort of pave. The way, in terms of some of these new norms, and yet, at the same time, there is not sort of a universally agreed upon structure or a series of regulations that everyone sort of adheres to when it when it comes comes to space, namely when it comes to, you know, interactions with Beijing. And I wonder, from your perspective, whether companies like Redwire can kind of establish almost a fait accompli when it when it comes to some of this, by operating in there and doing the kind of business that you’re doing so much so that becomes sort of an accepted norm in practice that maybe at some point, later on, becomes institutionalized.

Al Tadros – Yeah. Well, you know, I hadn’t thought about this before, but from (19)67 till the first launch of the shuttle, was only 13 years. And the vision of of shuttle, of of the shuttle program, which was started, you know, a few years after, you know, the Apollo program ended in (19)71 or (19)72 the vision was it was going to be shuttling things up. Is going to be shuttling humans up. It was going to be assembling things and fixing things and and so forth. So that treaty was really important, because we were about to do all this, you know, in the 80s, and quite frankly, that if you look at the some of the early shuttle missions, there was a lot going on, including Satellite Servicing, repairs, recovery.

We were bringing satellites back that were internationally owned, commercial satellites going on there that the treaty was very relevant to, and the fact that it’s now whatever, 40 years later. And we were thinking, wow, they were way ahead of their time. Well, it was expected that a lot of this was going to happen, you know, 30 years ago or more. So, yes, the like I started out with, it is some of the most exciting times ever, because we are going to the moon, and we’re going to stay and do things on the moon, and that matters to the treaty. And what, you know, what was envisioned there. We do have private habitats that are being developed for LEO. And that’s something that you know, before the ISS, you know, that was that’s unique and capable. We have a lot of satellites being put up. And that’s a whole world on its own, commercial and private satellites that are being launched into cislunar and beyond, which is a whole world and all these things, you know, have economies around them, government interests, international interests, and yes, the treaties matter now, okay, how are they being followed or implemented? Who is providing continuing supervision on these and how do we spur the economy?

Because the U.S. does want to retain it and continue growing in this regard. So Redwire is, as we were talking about earlier, has a lot of interest and and chops in this regard, with regards to commercializing and making it a sustainable business ecosystem. And we’re proud of that, of that history, over 30 year history of looking at that, including working on shuttle even before station and now on station, and then looking at lunar surface and private habitats as examples going forward. And we want to be part of the policy and regulatory aspects of that as we go forward.

David Ariosto – It strikes me. I mean, even if you’re outside the industry, it’d be hard not to kind of look at what’s going on, even just by reading the headlines casually and thinking, this is the beginning of something, this is the beginning of something that’s that’s markedly different and perhaps unprecedented in terms like the history of our species, even in terms of the fanning out beyond the, you know, the terrestrial confines that that is that has been Earth, I wonder, and this maybe just be our last question here, because we’re sort of wrapping up with time, but I wonder how you got into this, like, how, where did space factor into your own personal journey was this is like something that you’re always about as a kid, like looking up At the stars or watching the Apollo program, or what? Where’s this derived?

Al Tadros – Yeah, good question. Well, I grew up. My dad was an engineer. I grew up around the engineering thinking, and that was one element of it, but quite frankly, you know, I was right at the end of Apollo and before shuttle. But as a freshman in high school. Space Shuttle launched for the first time, and it was a big influence for me. It was spectacular. It was like out of sci-fi type of stuff, to see something go up and then land on wheels at a runway, yeah, with nuts coming out. I mean, it was in, you know, 1980 it was a bit surreal. So that was a huge influence and and then NASA had a lot of programs for high school students to get involved and so forth, and I entered some of those competitions and that that influenced me.

So I kind of it’s maybe a little bit of a choice, but straight out of, you know, freshman, sophomore year of high school, this is back when I had to go to the library to get. You know space, you know space news or Aviation Week at the time, type of magazines to read about and, you know, look at, but those kind of things influenced me quite a bit, and I stuck to it. And I ended up going to college in aerospace engineering. And, you know, a lot of what the research was I did in grad school and engineering was thinking about what we were going to do in the shuttle bays and building things in space and so forth. So that did influence me. And I’m fortunate to have worked in the space industry now for, you know, 35 years on a whole lot of things. But like I said, it’s some of the most exciting times I’m doing things now, like V LEO missions, which I hadn’t touched, you know, in the last 35 years. So it’s in the business aspects of it, acquiring companies and integrating companies new technologies. So it’s been an amazing career arc that, you know, I think a lot of people even joining right now would be thrilled to be part of so I’m excited by it, and I’m excited to work with new entrants. And, you know, you know, like I said, terrestrial industries to make use of space now,

David Ariosto – Yeah, it’s amazing. There’s always really the ripple effects, what happens in our childhood and what we see, kind of like, you know, carries out. And you know, the nature of the space industry now almost seems like it’s it’s perhaps even more exciting than than the 1960s and early 70s in terms of that golden era of what’s possible.

Al Tadros – Absolutely I believe it is.

David Ariosto – Al Tadros is the Chief Technology Officer at Redwire, and it has been just an absolute pleasure chatting with you. Thanks so much for joining us.

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly