Now Reading: Supernova blast sculpts ghostly hand-shaped nebula in the cosmos (video)

-

01

Supernova blast sculpts ghostly hand-shaped nebula in the cosmos (video)

Supernova blast sculpts ghostly hand-shaped nebula in the cosmos (video)

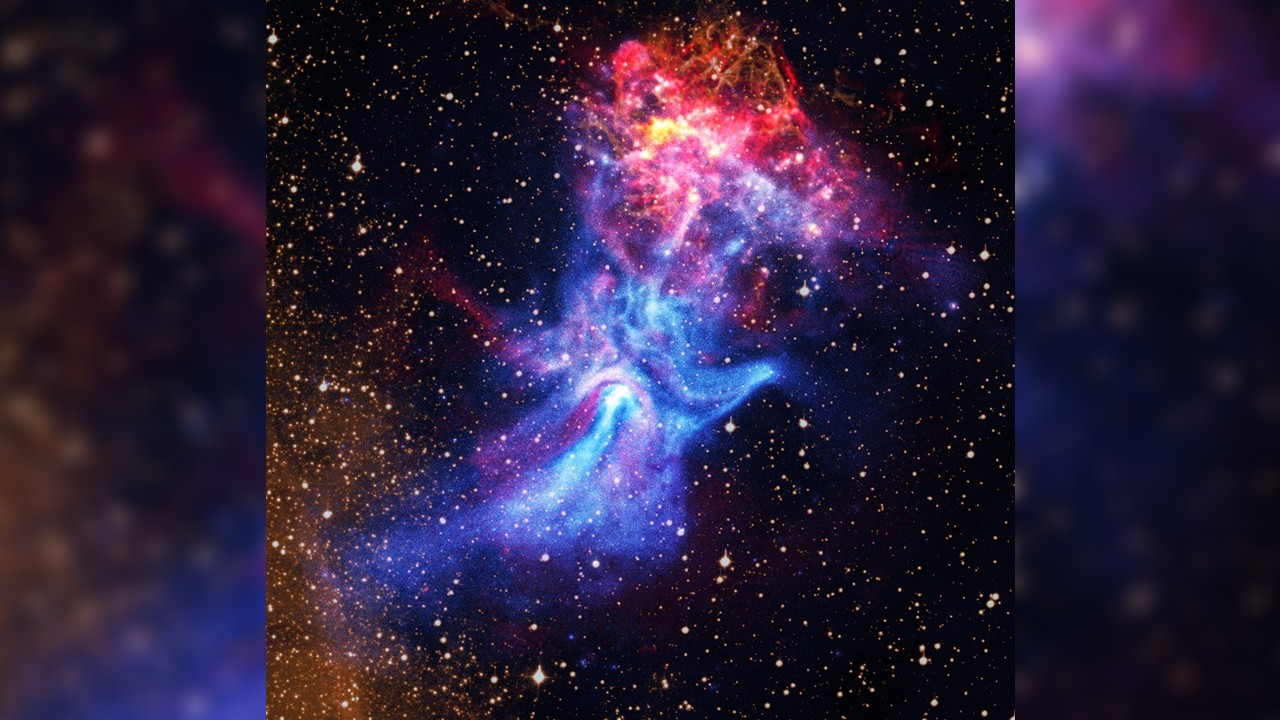

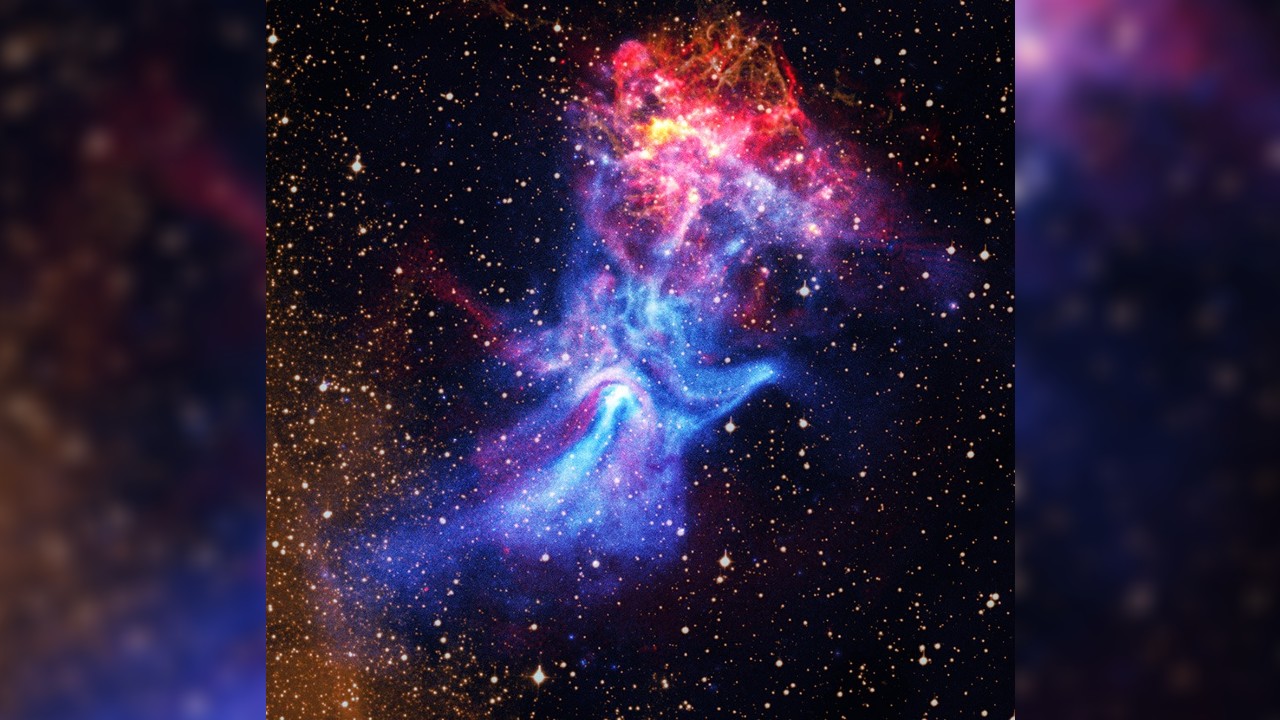

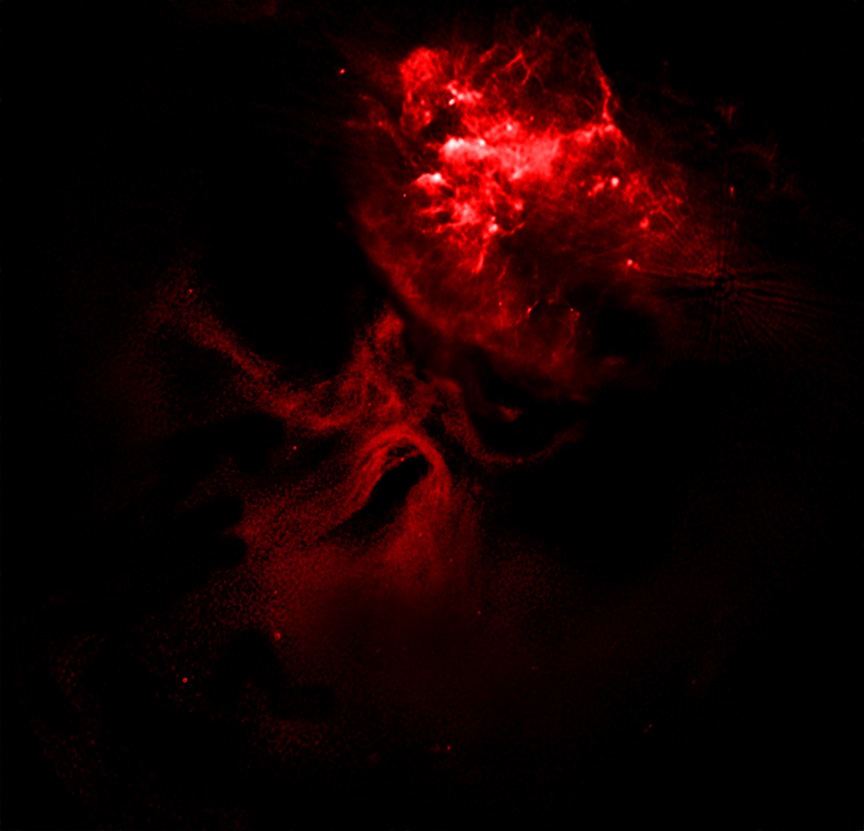

A glowing hand stretches across the cosmos, with its palm and fingers sculpted from the wreckage of a massive stellar explosion.

The eerie structure is part of the nebula MSH 15-52, powered by pulsar B1509-58 — a rapidly spinning neutron star that is only about 12 miles (20 kilometers) in diameter. By combining radio data from the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) with X-rays from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers created a new view of the nebula, which spans over 150 light-years and resembles a human hand reaching toward the remains of the supernova — formally known as RCW 89 — that formed the pulsar at the heart of the image.

“MSH 15–52 and RCW 89 show many unique features not found in other young sources,” according to a statement from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, releasing the new composite image. “There are, however, still many open questions regarding the formation and evolution of these structures.”

The central object, pulsar B1509-58, formed when a massive star ran out of fuel and collapsed before exploding as a supernova. The pulsar spins nearly seven times per second and has a magnetic field some 15 trillion times stronger than Earth’s. Despite its small size, it acts like a cosmic dynamo, accelerating particles to extreme energies and driving winds that carve the nebula into its hand-like form.

The new composite image paints the system in striking color: ATCA radio emission appears in red, Chandra’s X-rays glow in blue, orange and yellow, and optical data shows hydrogen gas in gold. Where the radio and X-ray signals overlap, they blend into purple, highlighting regions where the pulsar’s wind crashes into surrounding stellar debris.

The recent radio data uncovered delicate filaments aligned with magnetic fields, likely created as the pulsar wind smashes into leftover material from the stellar explosion.

Yet some of the most prominent X-ray features — including a jet near the pulsar and the bright “fingers” that extend outward — have no radio counterpart. Astronomers suspect these areas may be streams of energetic particles escaping along magnetic field lines, much like the shockwave from a supersonic aircraft.

Nearby, the supernova remnant RCW 89 contributes further mystery. Its patchy radio glow overlaps with clumps visible in X-rays and optical light, suggesting a collision with a dense cloud of hydrogen gas. Even stranger, a sharp X-ray boundary thought to be the expanding blast wave from the supernova shows no radio signal at all — an unexpected finding for a young remnant.

Together, MSH 15-52 and RCW 89 continue to intrigue astronomers. While the new image reveals new clues about the exploded star and its environment, further research is needed to better understand how pulsars and supernova debris interact to sculpt such stunning cosmic structures.

Their findings using the new high-resolution radio observations of MSH 15-52 and RCW 89 were published Aug. 20 in the Astrophysical Journal.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly