Now Reading: A double standard about contamination is keeping us from verifying signs of Martian life

-

01

A double standard about contamination is keeping us from verifying signs of Martian life

A double standard about contamination is keeping us from verifying signs of Martian life

NASA has announced that the properties of a rock in Jezero Crater qualify as a potential biosignature. The NASA Astrobiology Roadmap defines a biosignature as “an object, substance, and/or pattern whose origin specifically requires a biological agent.” By that standard, a confirmed biosignature would be as close as we can get to proof of alien life (though of course there is no final “proof” in the scientific method).

Rephrased in plain English: NASA found potential proof of alien life in our solar system. That’s a fact. But to know for sure, we need to start by bringing these samples home. Bringing potential evidence of Martian life back to Earth so it can be fully analyzed is worth the price tag, and worth loosening the overly strict “back contamination” rules. The cost of these biological containment measures are, in part, keeping the samples stuck on Mars.

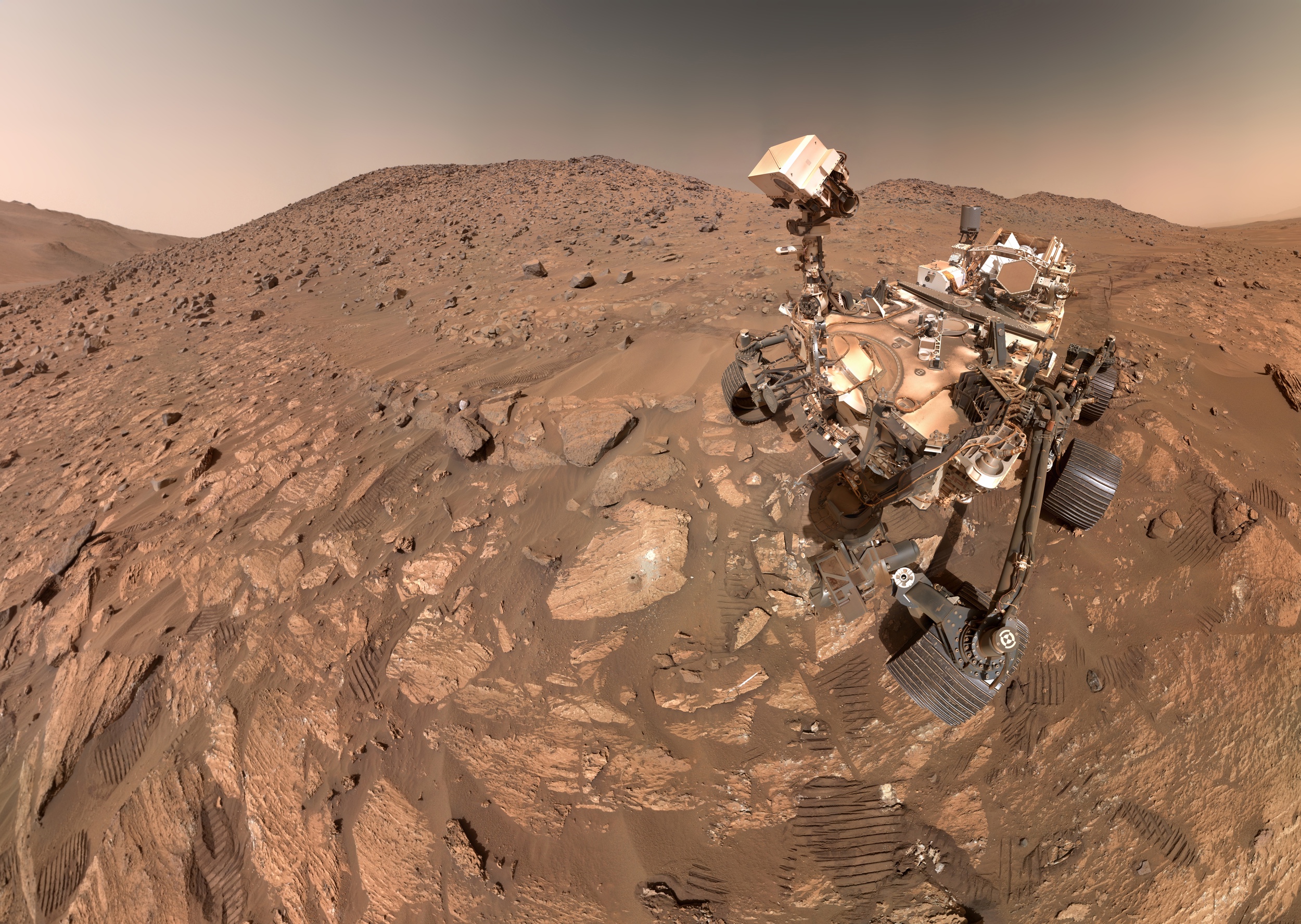

A “potential” biosignature is about as good as you can get without bringing a sample back. Without the ability to probe these rocks with instruments only found in Earth labs, we have been stuck with what tools we can put on a rover the size of a minivan. As capable as Perseverance may be, it is not even a fraction as capable as laboratories on Earth. We haven’t ever had a shot this big at discovering aliens, and now we have to take it.

If these samples really do indicate past life, it would be one of the greatest scientific discoveries of all time — on the level of Galileo showing Earth is not the center of the universe. A Nobel Prize would feel quaint in comparison. This could be a “big bang” moment for understanding the origins of life. And the evidence is already packed into tubes in the belly of Perseverance, giftwrapped and waiting to be returned.

It’s Christmas morning, and the best present under the tree just happens to be on Mars.

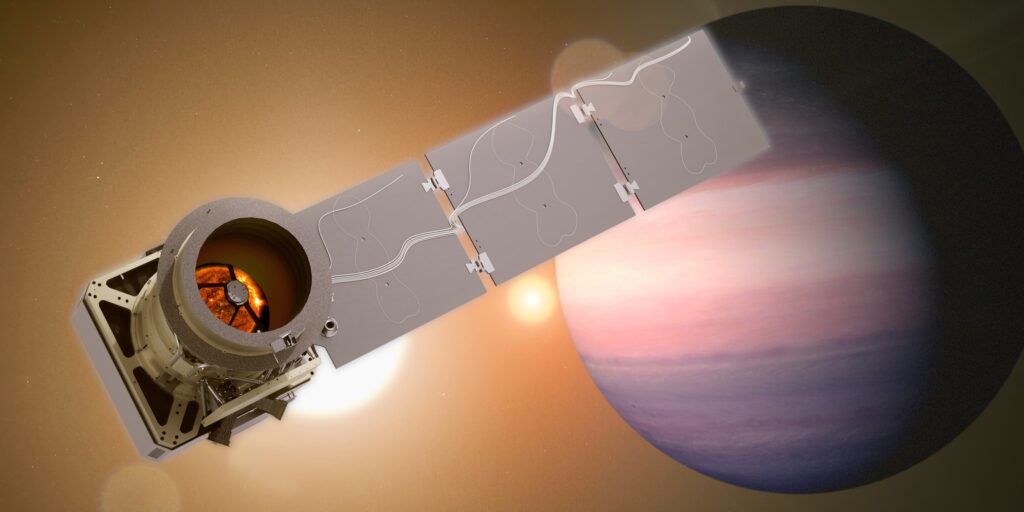

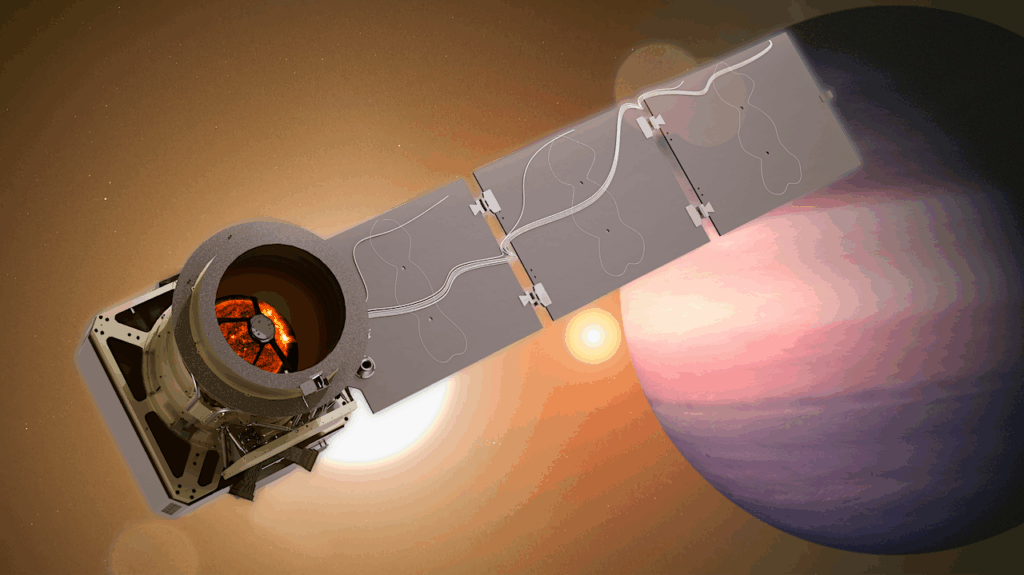

Getting those tubes back will be an incredible adventure that could inspire billions across the world. But Mars Sample Return (MSR), the NASA-ESA collaboration to do exactly that, is being slowly defunded and pushed into indefinite pause. Understandably, the mission is complex and expensive, but no more so than the James Webb Space Telescope. Most of the cost is driven by the difficulties of launching a sample from Mars and catching it in orbit, and by requirements meant to prevent Martian “back contamination” of the Earth-moon system.

Here’s the hypocrisy: Astronauts and SpaceX Starships will eventually land on Mars. Unless we plan to have astronauts die on Mars and never bring a Starship back, we will never abide by anything close to the level of biological containment (known as “planetary protection”) now demanded of MSR. Forward contamination — Earth microbes hitching a ride and colonizing Mars — is the real threat, because it could erase the very biosignatures we’re desperate to find. Yet the robotic MSR mission is held to an impossible standard for back contamination, even

though the Martian surface has been most likely blasted sterile by cosmic radiation for billions of years and meteorites from Mars have been landing on Earth for just as long.

This degree of paranoia around “Andromeda Strain” scenarios, where an extraterrestrial pathogen causes an outbreak, is not scientific. It is political, and NASA knows this. It has bloated this mission by billions. NASA subscribes to the strictest standards of internationally agreed guidance on this matter for MSR, but knows it simply cannot for crewed missions. Thus, MSR carries the burden of back contamination at massive expense, while Artemis and SpaceX account for neither. NASA needs to wake up to the fact that they will lose MSR altogether unless they choose a cheaper plan with fewer strings attached.

To be clear, NASA relies on the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR)’s planetary protection policy as the main way it demonstrates compliance with Outer Space Treaty (OST) planetary protection obligations, though it could meet the OST by other means if COSPAR policies ever diverged from U.S. interests, as they do now.

To contrast costs and benefits (at risk of marginalizing the particle physicists), the tangible significance of the Higgs Boson is still incomprehensible to me (even as a PhD scientist with a bachelor’s degree in astrophysics) and it cost about $13.5 billion to find. Compare that to the possibility of finding fossilized traces of Martian microbes for well under $10 billion if back contamination requirements are relaxed. Those findings would be physically visible, understandable and profoundly human. It is not an outlandish theory at all to suggest that these hypothetical Martian river creatures, if they are determined to have existed, could be our distant ancestral cousins.

What’s more, once returned to Earth, these rocks can someday be put on display for all of humankind to gaze upon behind a (thick, heavily guarded) pane of glass. The alien equivalent of footprints frozen in stone, inspiring us like the eighth wonder of the world, or more accurately the first wonder returned from another planet. “Dear City Council, think of the tourism dollars and the scientific brains that a sample like this would attract to your city if you help fund the Mars Sample Receiving Facility!”

I have been studying potential biosignatures on Mars since 2019, when I worked on Curiosity’s Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) detection system. Even then, we found sudden methane plumes, unexplained isotopic enrichments and long hydrocarbon molecules in surprising abundance. Exciting signals, but impossible to probe further with rover hardware. Many astrobiologists, from the 1970s to today, believe that something was left unresolved in the Viking results which dismissed positive life detection experiment signals due to a lack of detectable surface organics.

That was half a century ago, and now we know organics exist on the Martian surface. It led to a decades-long downturn in funding for Mars missions. As the Mars program recovered, evidence for past and present Martian life has only grown stronger. Yet NASA’s culture of extreme conservatism on the “aliens” question has calcified. It certainly has its reasons, but right now it’s deadweight. As NASA’s science budget gets hacked to pieces, and with more than 20% of their civil servants gone just nine months into the Trump presidency, we may never get another chance. So let’s call this what it is: retrieving what could be the most valuable set of objects in the universe. Lets shout it from the rooftops and cut through the red tape. They need to come home.

One final warning. If we don’t move quickly, someone else will. China’s Tianwen-3 mission aims to launch in 2028 and return samples by 2031. If they succeed first, they will claim the greatest scientific discovery of all time. We will be left explaining why we sat idle while Perseverance’s tubes gathered dust.

Chad Pozarycki worked at NASA Goddard on the Curiosity SAM team and did his PhD at Georgia Tech on detecting organic biosignatures in Martian planetary analogs. He is currently CEO of Deleon Technologies, Inc.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly