Now Reading: Redefining space diplomacy for the 21st century: from orbits to outcomes

-

01

Redefining space diplomacy for the 21st century: from orbits to outcomes

Redefining space diplomacy for the 21st century: from orbits to outcomes

While the world tracks the diplomatic rivalry between the United States-led Artemis Accords (which, with Senegal’s recent signing, is now at 56 member nations) and the China-led International Lunar Research Station partnership, at risk of being overshadowed is the international diplomatic and humanitarian work that’s already happening, enabled by the space community, thanks to state agencies, private firms, and non-profit organizations.

To make sure this humanitarian use of space is protected and expanded, responsibility must be shared. National governments should lead in safeguarding satellites that provide health and emergency services from counter-space threats. A trusted agency such as the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), multilateral coalitions like the International Charter or CEOS or a dedicated industry player should coordinate rapid, non-discriminatory access to commercial satellites during crises. Industry coalitions should help keep Earth observation data open, interoperable and actionable for health purposes. And governments working with NGOs and private firms should co-finance pilot projects that bring space-enabled services to last-mile communities. These four concrete steps form the basis of an “outcomes-first” paradigm in the evolving architecture of space diplomacy — a framework to advance here to shift the focus from abstract agreements toward measurable benefits for people on the ground.

Health and humanitarian imperatives are already furnishing common operational ground. The UNOOSA links bandwidth, Earth observation data and geospatial mapping to pressing public health imperatives. What matters most, now, is not how many agreements are signed, but whether satellites and the data they produce are actually saving lives, whether by connecting clinics, keeping emergency networks running, and enabling early responses to pandemics or outbreaks.

Looking at the success stories of some of these agencies and initiatives offers new blueprints for how space can deliver greater impact, reach more people and expand the range of use cases where orbital assets directly serve humanitarian and public health needs.

Frame connectivity as public infrastructure delivery. In rural Appalachia, Health Wagon mobile clinic incorporated Starlink satellite broadband to establish dependable telehealth capabilities in areas where terrestrial and mobile networks are essentially nonexistent. This implementation now enables the clinic to access electronic medical records, forward retinal imaging for analysis and conduct real-time, multi-disciplinary remote consultations. From a strategic perspective, the deployment illustrates how LEO backhaul can overcome legacy terrestrial limitations and strengthen systemic health resilience in geographically isolated populations. A comparable intervention in Guyana has, to date, 53 operational telemedicine stations and intends to expand to approximately 300 facilities by mid-2025 using satellite broadband — a deliberate strategy designed explicitly to address access and supply-chain constraints presented by rainforest terrain. The diplomatic conclusion is evident: satellite connectivity has transitioned from an aspirational agenda item to a tangible deliverable in the rubric of international space cooperation.

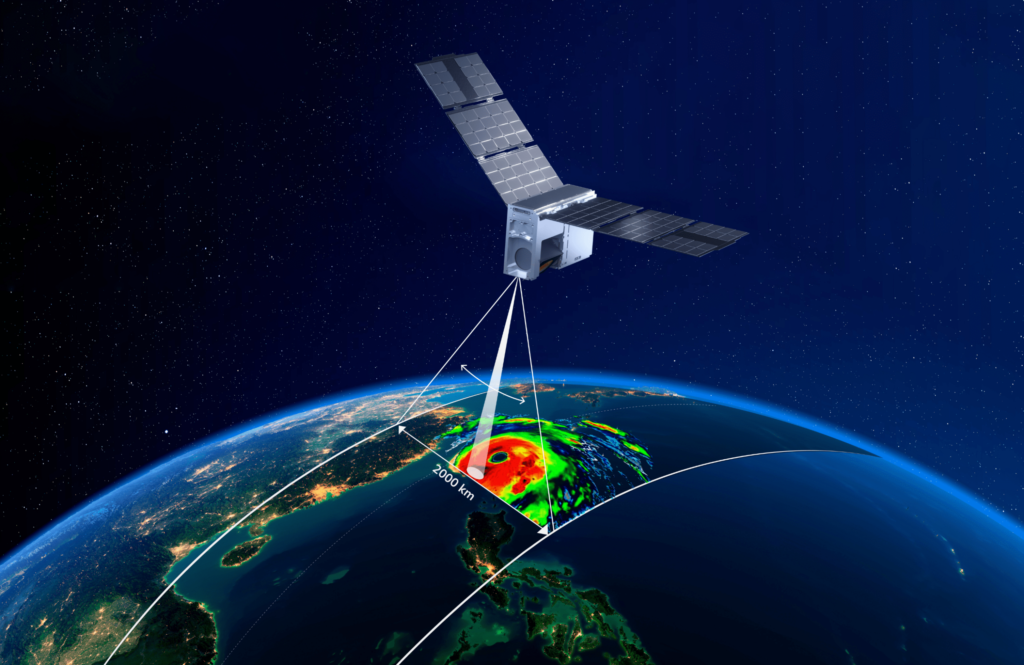

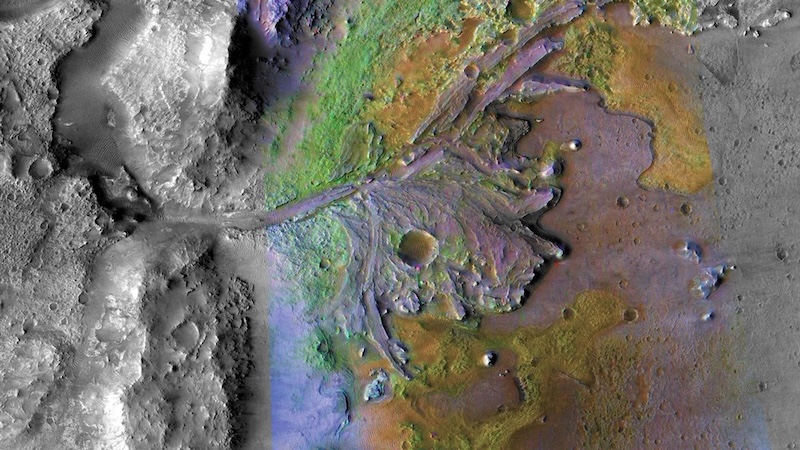

Earth observations are advancing preventive diplomacy. A NASA-supported consortium involving UNICEF and United Kingdom scientists has illustrated the potential of remotely sensed data by producing cholera risk forecasts for Yemen that enabled the forward deployment of humanitarian resources well in advance of the peak in transmission. This form of predictive diplomacy exemplifies the power of open data collaboration. When floods, seismic shocks or fires occur, the International Charter “Space and Major Disasters” immediately delivers high-temporal-resolution satellite data, while the UN-SPIDER program provides guidance on embedding Earth observations within national response structures. Maintaining the open-access Copernicus Sentinel archive and sustaining investment in analytics that convert raster data into epidemiological forecasts extend economic and humanitarian dividends between shocks.

The reasoning behind NGO and private-sector engagement is pragmatic. Multilateral treaties evolve at the pace of negotiations, public procurement cycles are inflexible and numerous ministries still lack the modular capacity to operationalize Earth services. NGOs and commercial operators prototype rapidly, operate seamlessly across borders and combine expertise with local players. NGOs’ neutral identity also helps them garner community trust and stabilize engagement. The corollary policy conclusion is to avoid outsourcing governance; instead, provide targeted operational funding and light-touch liability/data frameworks to quickly channel these actors’ capabilities in crises. The AstroAid Foundation, at which I serve as a volunteer ambassador, exemplifies the function of leveraging space assets to reinforce healthcare delivery. According to AstroAid founder Ahmed Baraka, the mission is to “enable advanced healthcare delivery to every individual on Earth through the catalytic power of outer-space technology.” To achieve that mission, AstroAid is executing near-term projects — launching miniature cubesats to transmit real-time telemedicine and public-health surveillance data — while also organizing virtual forums and global summits that convene space, health and humanitarian actors to co-develop regulatory safeguards, such as robust patient-privacy protocols.

Embedding outcomes-first cooperation into practice comes down to four steps:

- Protect humanitarian space services. Clarify and reaffirm the existing legal status of satellites supporting medical care, emergency communications and disaster relief as strictly civilian under under international humanitarian law. National governments, working through UNOOSA and COPUOS, should lead this effort, while industry associations promote voluntary or, where politically sensitive, de facto restrictions on actions, especially kinetic debris generation or jamming, capable of degrading systems that, while potentially dual-use, predominantly serve life-saving civilian missions.

- Standardize emergency access to commercial capacity. Institutionalize, through the International Charter, UN–SPIDER and regional authorities, standing protocols for swift bandwidth, imagery, and analytics requests. Governments must provide pre-agreed indemnification and compensation clauses to mitigate liability perceptions, while satellite operators commit to accelerating service during crises.

- Keep EO data open — and usable — for public health. Leverage Copernicus and Sentinel data, enforce open-access terms and finance “last-mile” tools that translate spectral and temporal data into actionable epidemiological indicators. Space agencies (e.g., ESA, NASA) should guarantee archives remain open, multilateral health organizations such as WHO and UNICEF should integrate them into epidemiological frameworks, and donor governments or development banks should fund usability tools. Recent cholera-forecasting successes quantify the epidemiological dividend of sustained, policy-driven access to calibrated EO inputs.

- Co-fund NGO/industry pilots to extend care to “dead zones.” Frame satellite-augmented telemedicine and health surveillance as pillars of national resilience, and seed sustainable models through targeted matching grants to operators and local health systems that track unambiguous economic and epidemiological outcomes. Governments and development banks should provide the grants, established humanitarian NGOs such as the Red Cross/Red Crescent (IFRC), PATH, or Doctors Without Borders (MSF) can serve as trusted implementers, while newer space-health organizations like the AstroAid Foundation bring innovation and a dedicated focus on space-enabled healthcare. Private operators should supply platforms, and health ministries should evaluate outcomes. Translating the Appalachia and Guyana experiences offers replicable roadmaps for parallel investment.

Low Earth orbit is now woven into the architecture of global health security. The networks that transmit retinal scans from remote health posts also sustain emergency command links when storms cut terrestrial fibers. The EO constellations mapping lunar poles are the same ones issuing cholera early warnings. The September 2025 Starlink suspension should be read as a geopolitical wake-up call: reliance on orbital systems has outpaced coherent governance. Elevating cooperative, socially beneficial space capabilities to a defined strategic imperative, with sustained investment, standards, and protective protocols, will strengthen resilience and credibility. This defines the core of 21st-century space diplomacy: shifting the focus from satellite deployment to the measurable human impact produced.

Elif Yüksel is a Turkish pioneer in space diplomacy and space policy. She is a Fulbright Scholar, Space Policy Institute Fellow, and an alumna of the International Space University. Currently, she works as a consultant for several private space companies and voluntarily serves as an Ambassador for the AstroAid Foundation.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these op-eds are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits