Now Reading: ‘Left of launch’ becomes central focus in next-generation missile defense

-

01

‘Left of launch’ becomes central focus in next-generation missile defense

‘Left of launch’ becomes central focus in next-generation missile defense

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. — Even with dozens or hundreds of sensor satellites in orbit to spot incoming weapons, U.S. military leaders say defending against the most advanced missile threats will require capabilities to disrupt these attacks “left of launch.”

This has emerged as a key focus in efforts to defend the U.S. homeland and military forces overseas against new classes of missiles the Pentagon sees adversaries developing. “Left of launch” refers to measures aimed at preventing or delaying missile launches, rather than solely relying on interceptors to destroy them in flight, a more traditional “right of launch” approach.

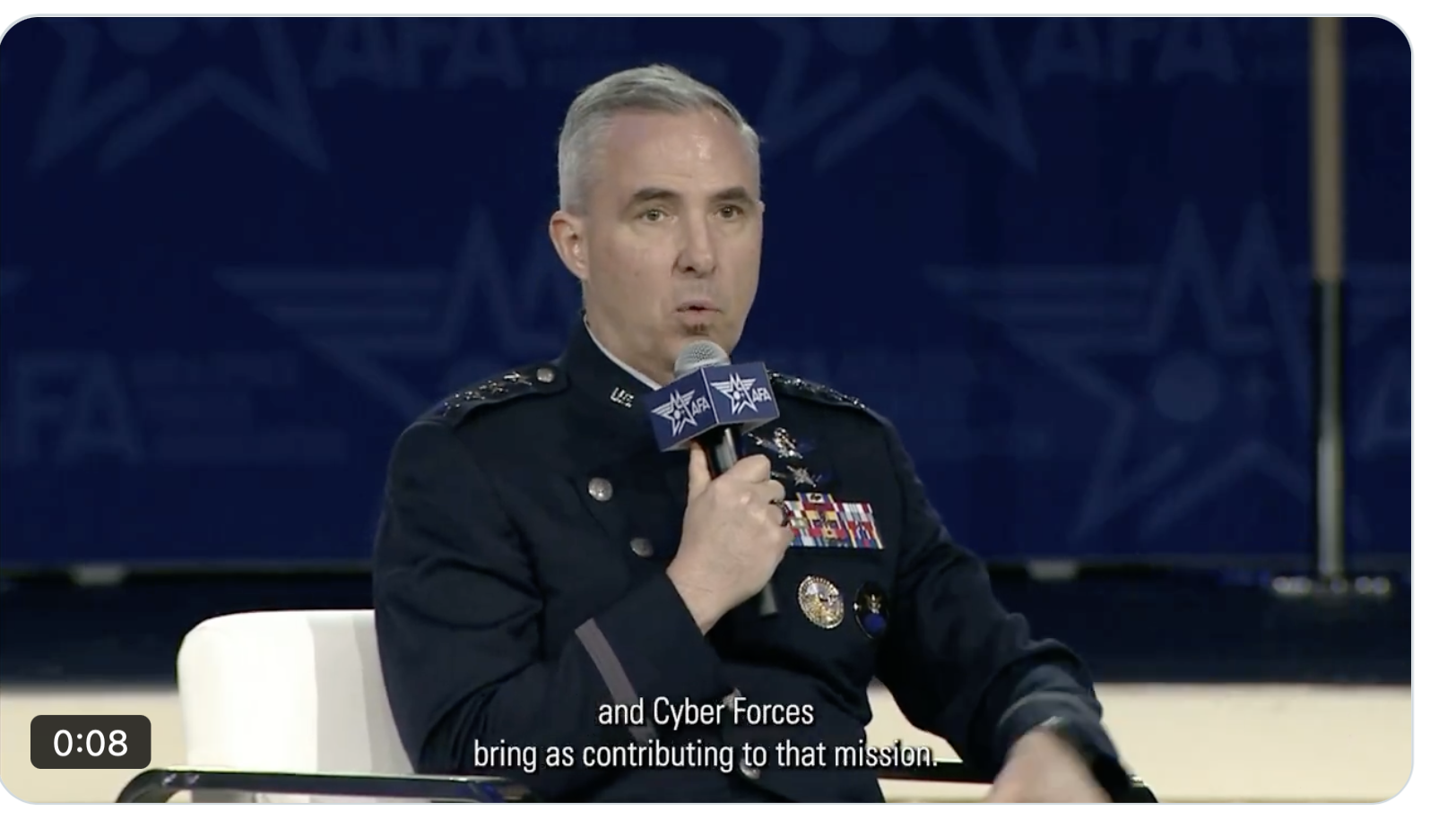

Speaking Sept. 24 at the Air Space & Cyber conference, Gen. Stephen Whiting, commander of U.S. Space Command, said missiles being developed by China, Russia and other nations are becoming more dangerous and more concerning.

“We are seeing both the capacity and the capability of the threat missiles we’re now facing rapidly increase,” he said. “Just look over the last 18 months in the Israel-Iran conflict … multiple salvos of missiles, not single digit missiles, not double digit missiles. We’re talking triple digit missile salvos paired with one-way attack drones.”

Current U.S. military missile warning satellites are “very good at tracking traditional ballistic missiles,” Whiting explained. However, to deal with the more sophisticated threat missiles — including maneuvering vehicles with hypersonic weapons, with fractional orbital bombardment systems that launch into an orbit and then de-orbit right on top of a target — the Space Force and other agencies have been working for years developing better tracking from low and medium altitude orbits “to maintain custody of these threats, because just tracking and boost phase detection is no longer good enough. You’ve got to track all the way through to the terminal phase.”

Cross-domain collaboration

Whiting has been a proponent of closer “space-cyber-SOF” collaboration, highlighting that there are synergies between the space and cyber domains, and the covert work of special operations forces. The idea of “left of launch” missile defense is an example of how this collaboration might work because it integrates unique strengths from each domain to detect, disrupt and potentially stop missile threats before they are ever launched.

Whiting discussed the topic on a panel with Lt. Gen. Sean Farrell, deputy commander of U.S. Special Operations Command; and Lt. Gen. Thomas Hensley, commander of Air Forces Cyber.

In theory, this collaboration means that while Space Command provides persistent surveillance and tracking through space-based sensors, allowing early detection of moving missile launch platforms, Special Operations Command operates covertly on the ground to gather intelligence on missile forces or conduct direct actions to neutralize launchers. Meanwhile, Cyber Command adds the capability to infiltrate or disrupt an adversary’s missile command and control networks via offensive cyber operations, potentially preventing launch orders from being executed.

This type of integration ideally shifts missile defense from reactive interception to proactive deterrence and disruption, Farrell said, highlighting SOCOM’s work trying to counter drone strikes.

“General Whiting spoke about ‘left of launch,’” said Farrell. “We have been working left of launch on behalf of the department, to try to understand how we can get after the threats, before they become a threat.”

“If we’re able to synchronize and plan together at the strategic level,” that approach can be applied to a layered homeland defense, he added.

The shift carries significant economic implications. If threats can be thwarted before launch, Farrell noted, it “shifts the cost calculus” because the United States doesn’t have to deploy expensive interceptor missiles to take down a low-cost drone, for example.

A similar scenario applies to space threats, said Whiting. “China and Russia have demonstrated they can take us on in the space domain with their non-kinetic jammers with direct ascent anti-satellite weapons, with high energy lasers, with co-orbital anti-satellite weapons, but they would much rather take us on using cyber or their special operations forces, because it’s cheaper for them and harder for us to attribute,” he said.

Advanced sensing capabilities

When it comes to cruise missiles or one-way attack drones, said Whiting, “we want to be able to do a better job of helping to track those threats from space, which is why you see a discussion now of moving AMTI potentially to space.”

AMTI, or Air Moving Target Indicator, are sensors designed to detect, track, and characterize airborne moving objects across wide areas. These sensors would provide “target custody,” meaning they can keep continuous track of a threat object throughout its entire flight.

The Air Force and the Space Force are studying options to field a new layer of AMTI satellites that would support “left of launch” interdiction and complicate adversary planning cycles.

“Our missile defenses have broadly done a good job during the most recent conflicts, but most of those are focused on terminal engagement, and we want to be able to push that engagement to the left and eventually left of launch,” said Whiting. “And if we’re going to do that, it’s going to take this integration, this nexus of cyber SOF and space, to drive capabilities that allow us to affect targets before they even begin to launch.”

Next-generation missile defense

These discussions are taking place as the Pentagon embarks on an ambitious defense initiative: the Golden Dome system mandated by President Donald Trump in a January 2025 executive order. The program is intended to protect the continental United States from ballistic, hypersonic, and cruise missile threats through a global network of sensors and interceptors.

None of the officials speaking at the Air Space & Cyber conference specifically mentioned the Golden Dome program, which is run by a separate program office led by Space Force Gen. Michael Guetlein.

Meanwhile, across the defense industry, companies are awaiting details from Guetlein’s office about what capabilities the Pentagon will seek in Golden Dome and what the architecture of the system will be, including how it views the “left of launch” question.

Per Guetlein’s guidance, “we don’t want to speculate on what Golden Dome is” until the architecture report is completed in the coming weeks, Rob Mitrevski, president of Golden Dome strategy and integration at L3Harris Technologies, told SpaceNews.

The company is a major player in missile defense with decades of experience in radar systems and space-based sensors.

“Golden Dome is multi-domain, it’s multi-layer, it’s regional, national, global, it’s left of launch, it’s right of launch,” he said.

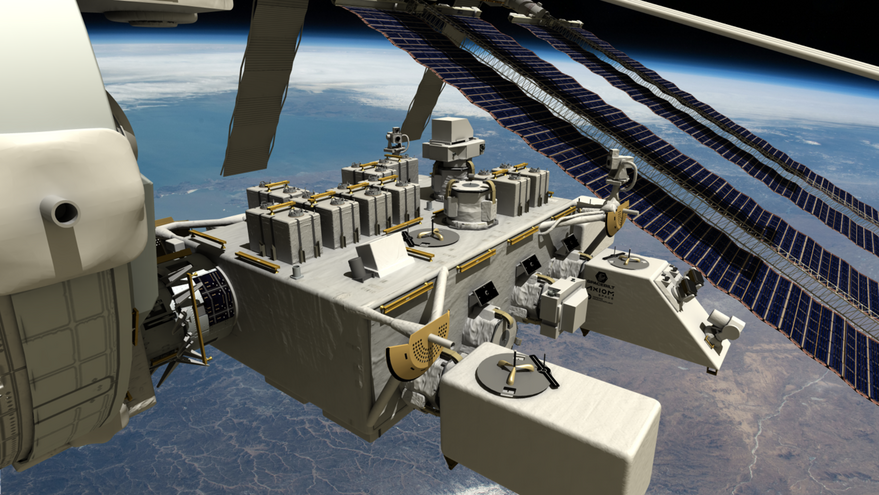

With regard to “left of launch capabilities,” Mitrevski said the Pentagon is well positioned with a number of satellite sensor programs run by the Space Force and the Space Development Agency, which potentially could be accelerated under the Golden Dome umbrella.

Space-based interceptors

The industry is closely watching what the Pentagon decides with regard to the overall system architecture and how quickly it might move forward with plans to develop new layers of sensor satellites and space-based interceptors.

The Space Force’s Space Systems Command on Sept. 16 released a request for prototype proposals for the Space Based Interceptor (SBI) program. An RPP is an official solicitation inviting companies to submit ideas for developing, prototyping and testing interceptor weapons that could be deployed in space to defend against missile attacks on Earth.

Companies will be challenged to design prototype SBI systems capable of intercepting missiles both within the atmosphere and after they enter space, progressing through stages.

“Like everyone in the industry, we’re following this,” Mitrevski said. “We’re ready to provide solutions.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits