Now Reading: JWST delivers 1st weather report of nearby world with no sun — stormy and covered with auroras

-

01

JWST delivers 1st weather report of nearby world with no sun — stormy and covered with auroras

JWST delivers 1st weather report of nearby world with no sun — stormy and covered with auroras

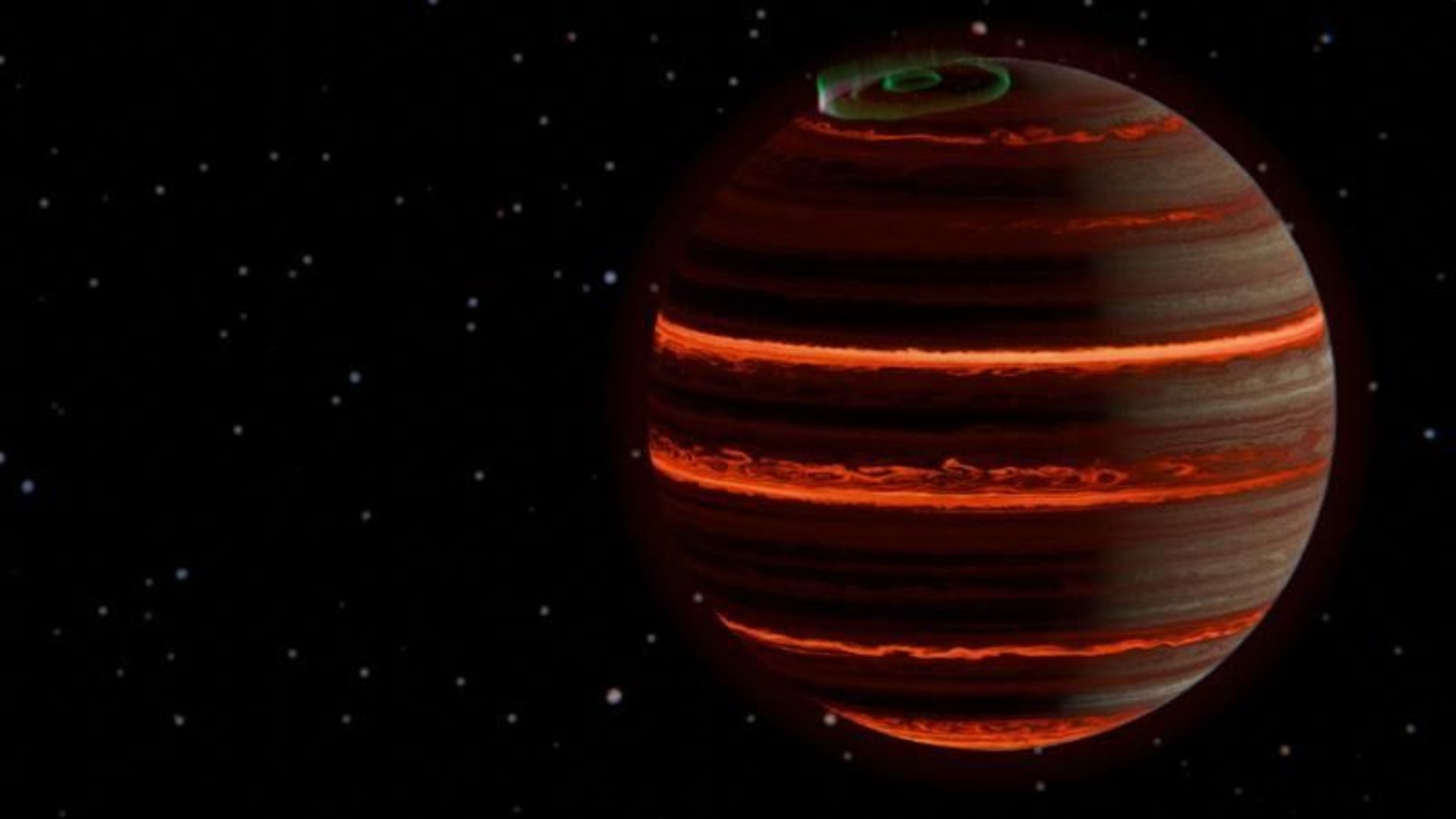

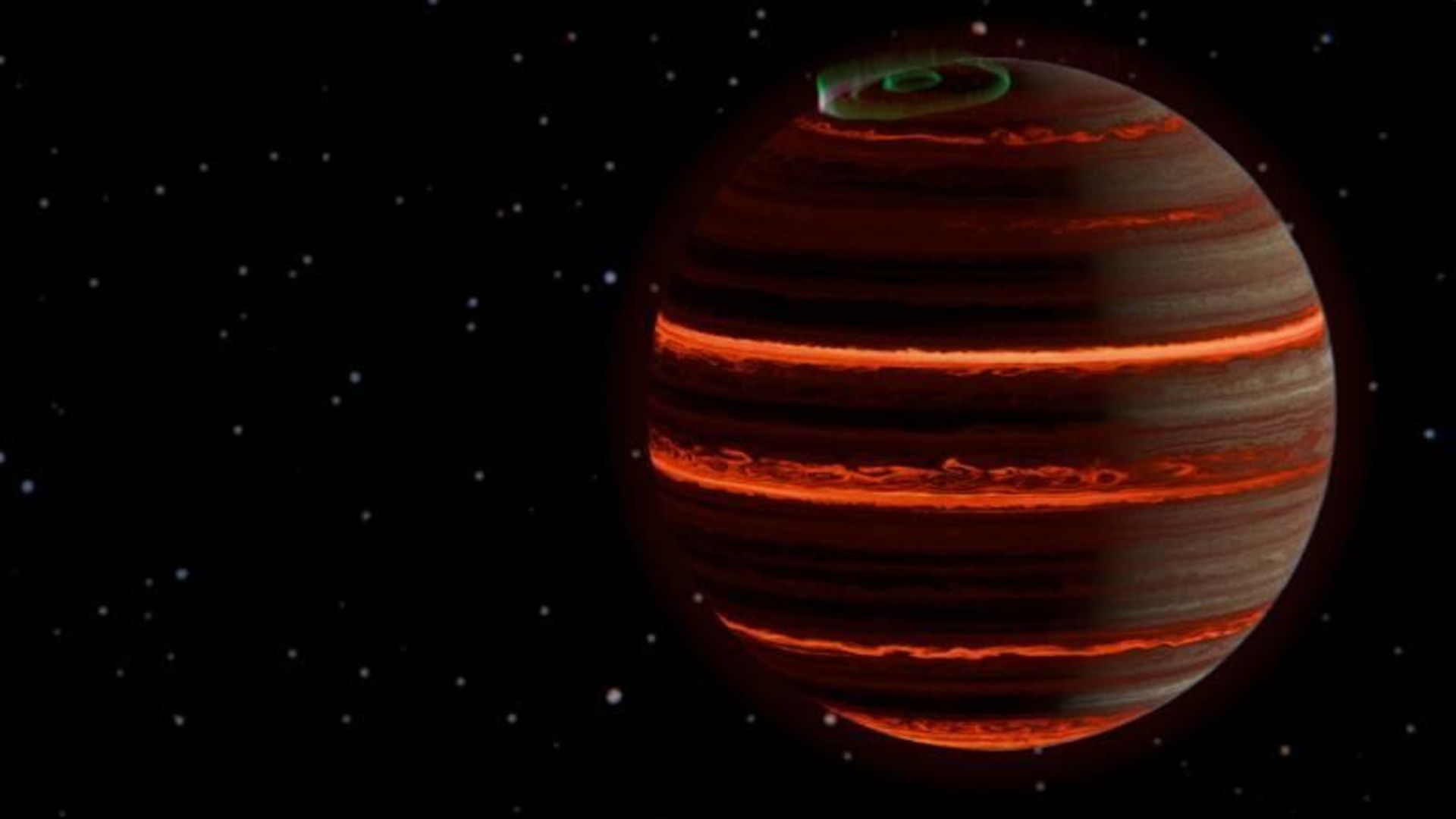

The latest weather forecast doesn’t come from Dublin, London or New York — it comes from deep space, where a lonely world drifts without a sun and glows with auroras more dazzling than Earth’s northern lights.

The world, called SIMP-0136, is about 200 million years old and lies about 20 light-years away in the constellation Pisces. It isn’t quite a world nor a star. Astronomers classify it as a brown dwarf, sometimes dubbed “failed stars.” Like stars, this world forms from collapsing clouds of gas, but it never grows massive enough to sustain hydrogen fusion in its core — the defining trait of a star.

And unlike Earth, SIMP-0136 doesn’t orbit its own sun. It’s a rogue world that spins once every two and a half hours as it floats freely through space. Now, thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have delivered the most detailed “weather report” yet for this strange world, tracking subtle changes in its atmosphere over a full rotation.

The study, published Sept. 26 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, is the first to track how a brown dwarf’s atmosphere changes as it spins, revealing shifts in temperature, chemistry and clouds. Astronomers say the findings open a new window onto the weather of worlds beyond our solar system.

“These are some of the most precise measurements of the atmosphere of any extra-solar object to date, and the first time that changes in the atmospheric properties have been directly measured,” study lead author Evert Nasedkin of the Trinity College Dublin in Ireland said in a statement.

“Understanding these weather processes will be crucial as we continue to discover and characterise exoworlds in the future,” study co-author Johanna Vos of Trinity College Dublin said in the same statement.

The JWST’s sensitive instruments captured minute changes in brightness as SIMP-0136 spun, letting scientists map its atmospheric layers. Astronomers had long suspected the flickering light came from patchy clouds. Instead, the study found that SIMP-0136’s clouds, made of sand-like grains of hot silicates, are remarkably stable.

The real drama was instead unfolding higher up in the atmosphere, where the team discovered a layer of air nearly 570 degrees Fahrenheit (300 degrees Celsius) warmer than models predicted. According to the study, the extra warmth is most likely caused by auroras.

On Earth, auroras appear as shimmering curtains of light when charged particles from the solar wind interact with our world’s magnetic field. On SIMP-0136, however, a much stronger magnetic field supercharges this effect, with charged particles slamming into the atmosphere so forcefully that they not only glow but also pump energy into the air itself, heating the world’s upper layers.

JWST also detected tiny temperature swings of less than 40 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) in deeper layers, the study notes. Those tiny temperature changes might be caused by huge storm systems, possibly like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, moving across the surface as the world spins, scientists say.

Because brown dwarfs like SIMP-0136 aren’t swamped by the glare of a parent star, they serve as ideal stand-ins for giant exoworlds that orbit distant suns. By studying their weather in such detail, astronomers are beginning to piece together how atmospheres behave on distant worlds.

With JWST and future observatories such as the Extremely Large Telescope and NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory, astronomers hope to use the same techniques on worlds orbiting distant stars and uncover how their weather shifts and evolves over time.

A study about these results was published on Sept. 26 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

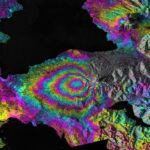

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly