Now Reading: International Observe the Moon Night 2025: 4 things to see on the lunar surface on Oct. 4

-

01

International Observe the Moon Night 2025: 4 things to see on the lunar surface on Oct. 4

International Observe the Moon Night 2025: 4 things to see on the lunar surface on Oct. 4

International Observe the Moon Night 2025 is upon us! Here’s what to look for when the lunar disk rises above the eastern horizon on Oct. 4.

Each year NASA teams up with a host of international partners to hold events to engage the public in observing the moon and learn about humanity’s efforts to explore Earth’s natural satellite. Be sure to check out the Observe the Moon Night website to explore over 950 virtual and in-person events that are being held to mark the occasion!

To celebrate, we’ve put together a list of stunning targets to observe through a telescope, binoculars, or with the naked eye that showcase the diverse nature of the lunar surface.

5 lunar targets to celebrate Observe the Moon Night 2025

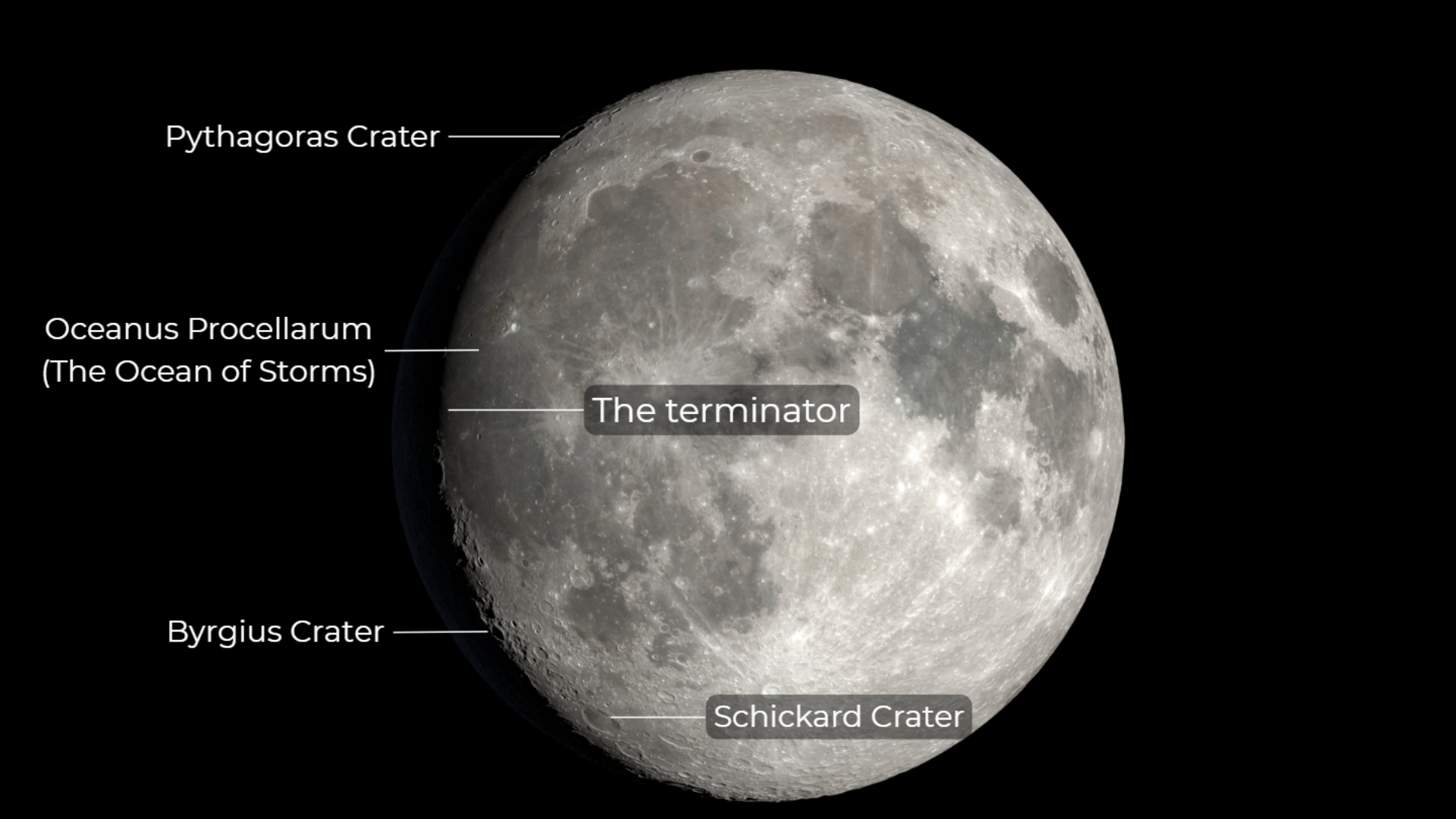

1 – The terminator

The line separating night from day on the lunar surface is known as the terminator. On Oct. 4, this shadowy divide will fall over the extreme left side of the 95%-lit moon, just two days before it reaches its full moon phase on Oct. 6 and gives rise to a spectacular full “Harvest Supermoon”.

Look to the top of the terminator to see the shadow-drenched form of the 75 mile-wide (120 kilometer) Pythagoras Crater scarring the lunar surface, while to the south the western rim of the sprawling Schickard Crater is thrown into relief below the striking oval form of the impact crater Byrgius.

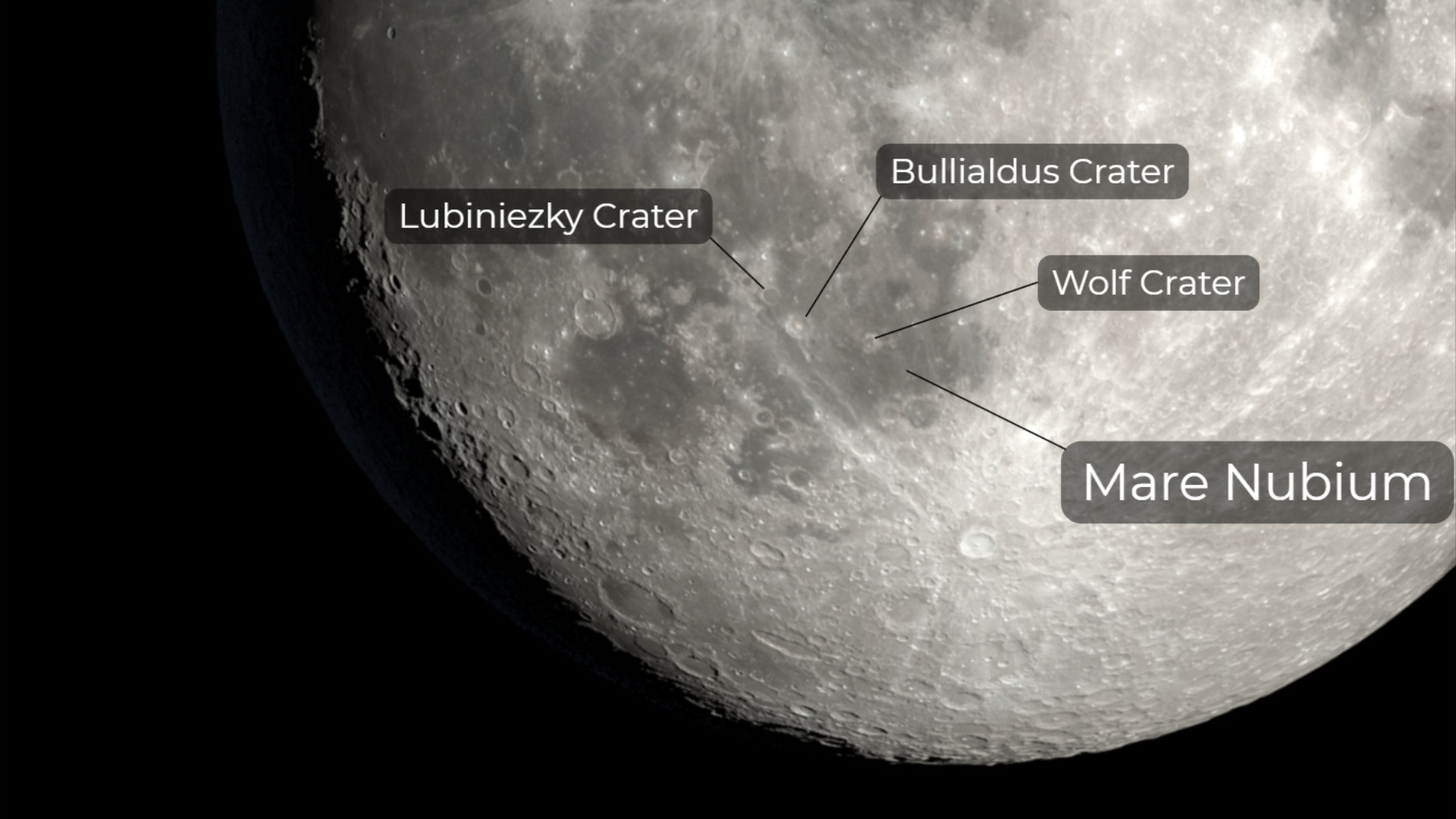

2 – Mare Nubium

Look south of the moon’s equator on Oct. 4 to find Mare Nubium (Latin for “the Sea of Clouds”) darkening a vast swathe of the lunar surface, with the prominent Lubiniezky, Bullialdus and Wolf craters pockmarking this basalt plain.

The lunar seas were formed billions of years ago when lakes of lava flooded networks of impact basins excavated by brutal asteroid strikes. The lava subsequently cooled and solidified to repave the lunar surface, leaving vast regions that appear relatively unscathed by the bombardment that ravaged the more ancient parts of the lunar surface.

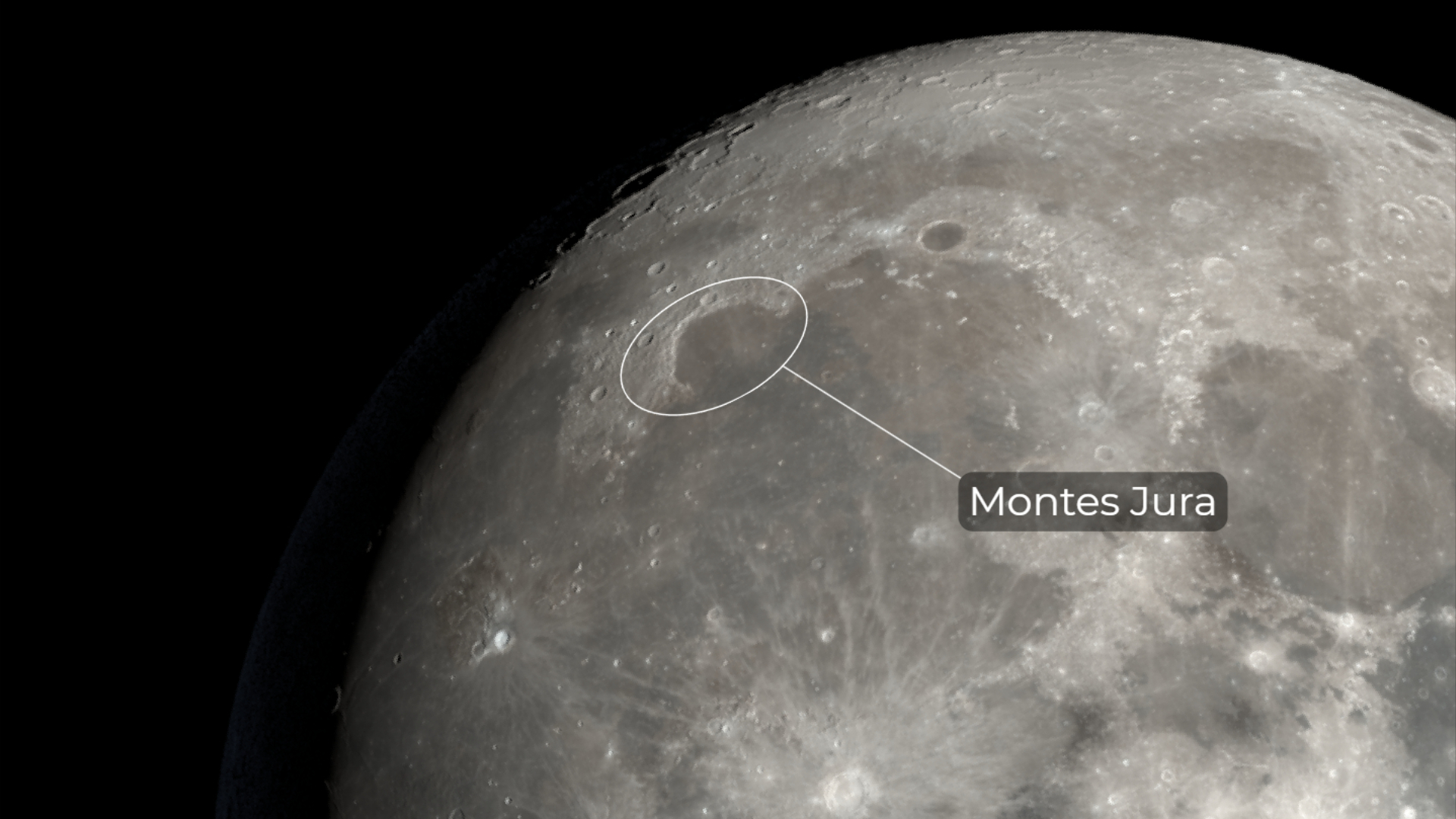

3 – Mountains surrounding the “Bay of Rainbows”

Montes Jura is a vast mountainous range of terrain bordering the northern edge of the Sinus Iridum (Latin for “Bay of Rainbows”) impact site. The upper peaks are perfectly positioned to catch the sun’s light around 11 days after the monthly new moon phase, making it appear as if a vast “Golden Handle” resides upon the lunar surface.

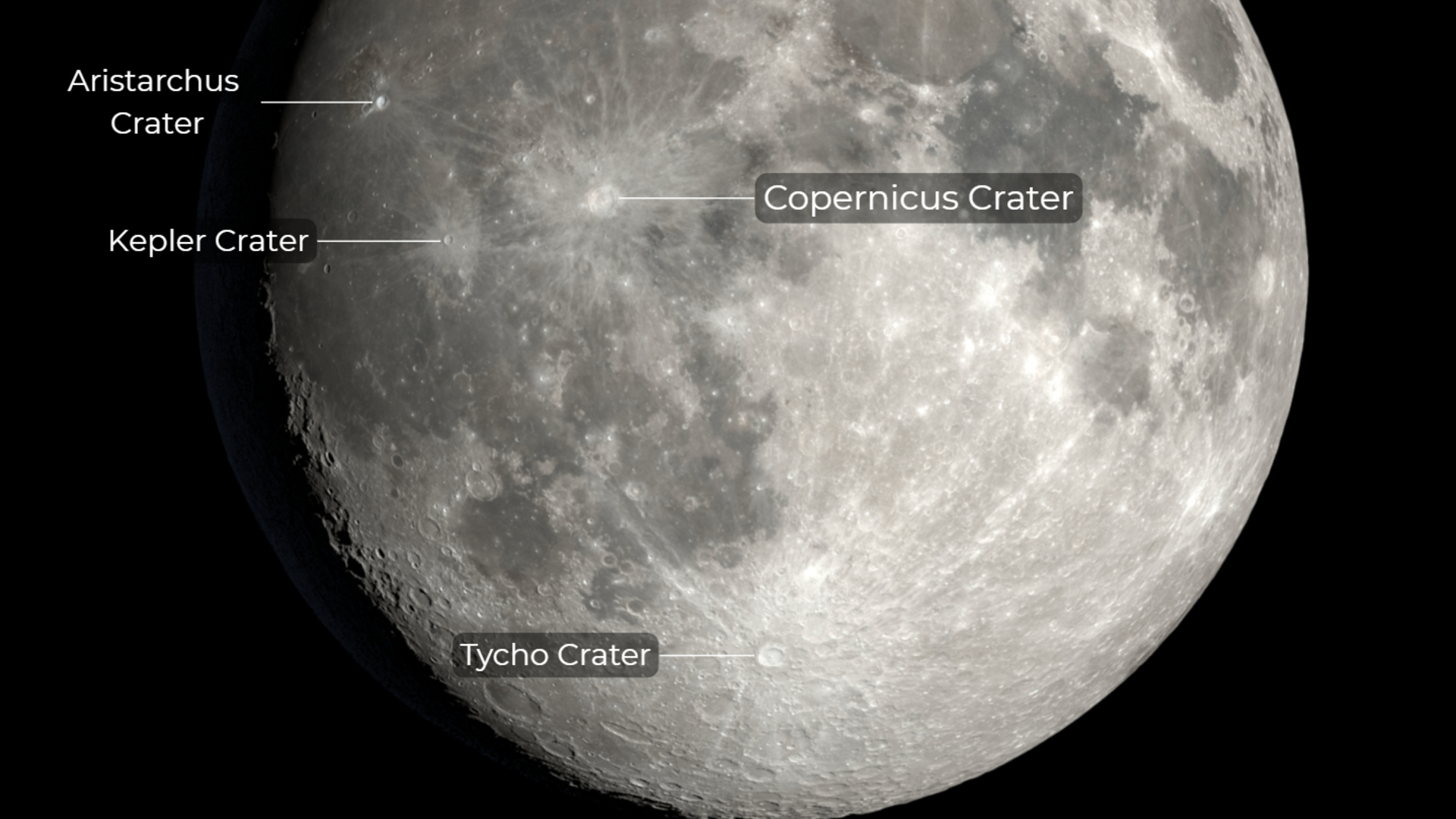

4 – Ejecta rays

The nights surrounding a full moon phase are the perfect time to spot ejecta rays brightening the lunar surface. These bright streaks emanating from craters are formed when asteroid strikes cast out reflective material from the moon’s interior and can extend for hundreds of kilometers. Tonight, look for them streaking away from large impact sites such as Kepler, Copernicus and the 53-mile-wide (85 km) Tycho Crater that dominates the south lunar surface.

All impact craters once boasted ejecta rays of their own, which become dulled with prolonged exposure to the space environment. The ones we see today are relatively young, with Tycho for example being just 108 million years old.

Editor’s Note: If you capture an image of the lunar surface and want to share it with Space.com’s readers, then please send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly