Now Reading: Living in space isn’t just a challenge for astronauts. Their families feel it, too

-

01

Living in space isn’t just a challenge for astronauts. Their families feel it, too

Living in space isn’t just a challenge for astronauts. Their families feel it, too

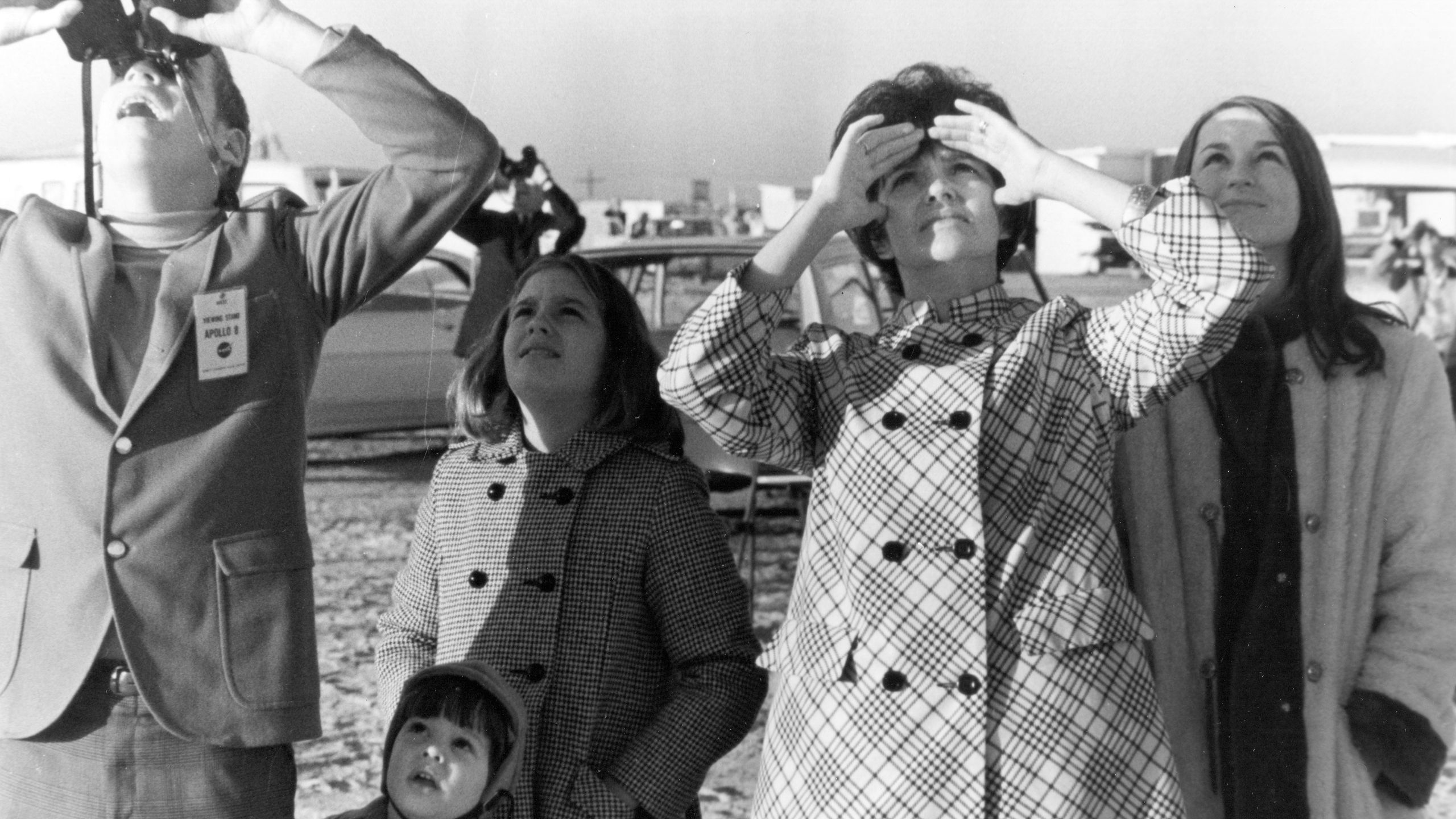

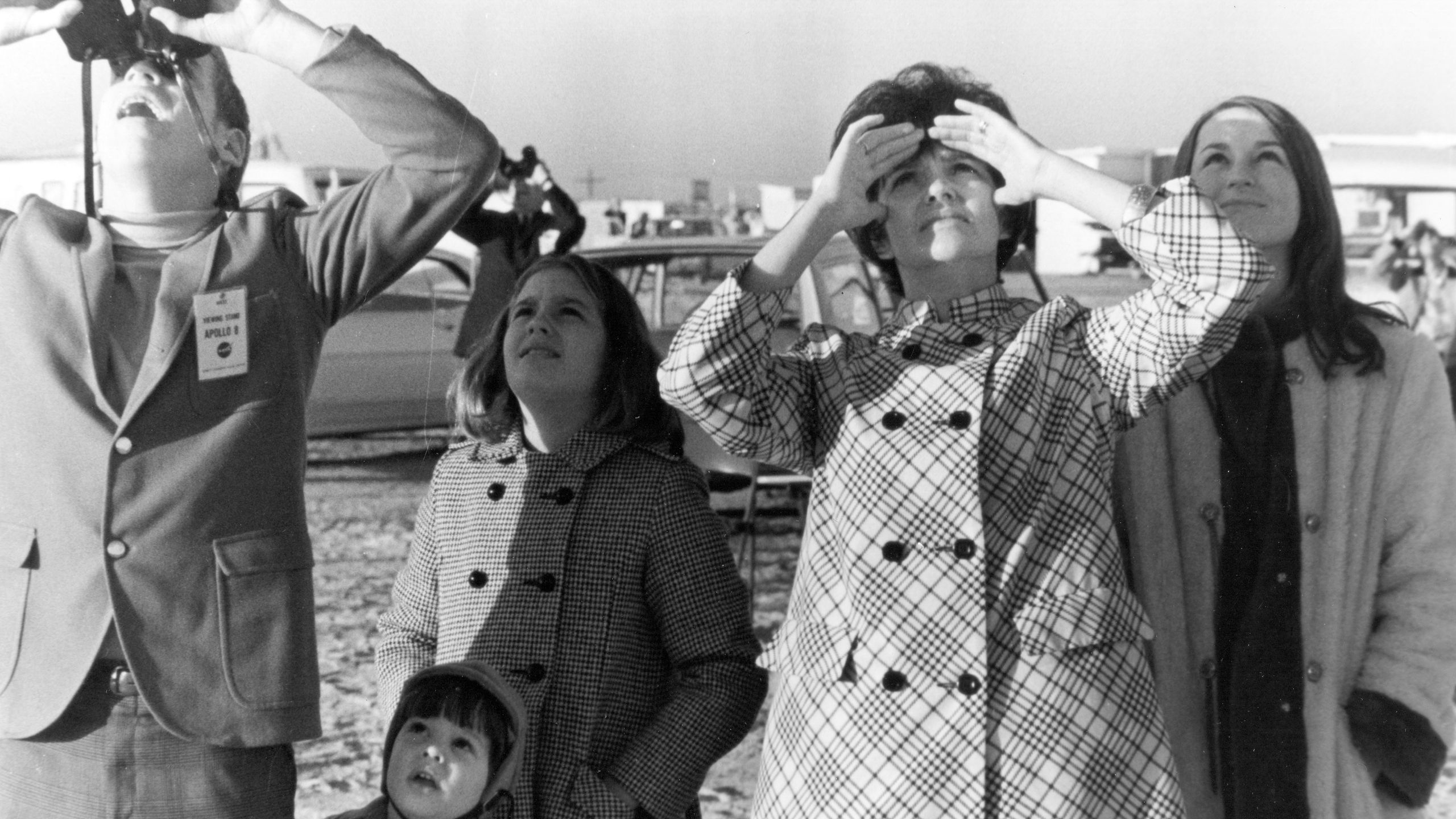

If you’re a space buff but haven’t already seen the 1995 film “Apollo 13,” it’s worth the watch. It recreates the near-disaster mission marked by an oxygen tank explosion and emergency ocean-landing back to Earth starring Tom Hanks as Jim Lovell, Kevin Bacon as Jack Swigert and Bill Paxton as Fred Haise: the heroic crew at the center of the story. But in addition to telling the tale that involved the infamous (and often misquoted) line “Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” it also weaves in the intimate family lives and relationships of the three people on that fateful mission.

I remember first watching the movie as a kid; it was those family details that stuck with me (and Kevin Bacon’s screentime, to be fair — I was a huge fan of “Tremors”). Specifically, I vividly recall scenes in the Lovell family living room where Jim’s wife, Marilyn Lovell, and all the other astronaut family members gathered around a TV, watching the destiny of their husbands and fathers dangling perilously in outer space.

The public’s interest in astronaut family lives, and specifically the Lovell family’s experience, isn’t a novel one — there’s even a book and TV series called “The Astronaut Wives Club” documenting, you guessed it, the lives of astronauts’ wives. But Hollywood spins and fictionalized glamour aside, how are the families of astronauts really impacted by their space travel day-to-day? Are there metrics to show the consequences, such as divorce rates or child well-being statistics? How do the space travelers themselves feel about leaving everyone they’ve ever loved or known down below?

Similarities with the military

While astronauts do not leave home to go to war or face combat, families of space travelers may share a few commonalities with military families in which one member is an active service member. In both cases, a parent or partner leaves for extended periods of time due to work and there is heavy risk associated with that work.

“Just like the military spouse feels every time they’re deployed, you don’t really know if something’s going to happen. You just kind of live in vigilance the whole time, Air Force Col. Catie Hague told Military.com. Hague’s husband, Nick Hague, was on the rocket that experienced a booster failure a couple of minutes into launch.

According to a 2018 systemic review published in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, which compared kids from military and non-military families, having a deployed parent led to a greater risk of some adjustment issues in kids, such as substance use. The authors concluded that on the whole, the well-being of military and civilian children wasn’t that different.

The same journal also pointed out that children of military families see benefits that positively affect the family structure, such as a parent having steady income and a stable job. Lower socioeconomic status has been linked to a likelihood of poor health outcomes for children.

While there are similarities between military life and space life for people who love someone who participates in either, there are also big differences, according to Stacey Morgan, wife of astronaut U.S. Army Col. Andrew Morgan. In an article originally written for Houston Moms Blog and then republished by the U.S. army, Morgan writes that the “public nature of the astronaut persona” makes for a different experience.

For example, an astronaut’s family member at home watching footage of them traveling to space is watching it at the same time as everyone else.

“The idea that we as a family are sharing these phenomenal yet perilous moments with the world, literally at the same time as we experience them for ourselves, can be unsettling,” Morgan wrote.

“Just like the military lifestyle, the astronaut lifestyle is hard on the family.” – Catie HagueOne of the most important team players who contributes to the success of my mission on @Space_Station and at home is my wife. Thanks for being our rock. https://t.co/ZzCk4TMwy8 pic.twitter.com/x9Hfino8csAugust 30, 2019

In a 2023 Viewpoint article published in Space Policy, the authors make the case that families of space travelers may be better prepared to handle their family member’s flight by utilizing the Families Overcoming Under Stress (FOCUS) model — a behavioral health model and program made for the families of active military members to help them better-manage the stress and potential mental health problems that may arise. The same article points out that all space travel may not be created equal: Loved ones of people who pay to go to space (SpaceX and Blue Origin space tourists, for example) may feel that they “did not sign up for the stress and dangers” associated with space travel, the authors write, while the family of a trained astronaut or space scientist may be better accustomed to whatever occupational hazards the job entails.

All types of space strains

At least at the time of this writing, there appears to be a lack of official research on how space travel and astronaut life affects the family unit, how it impacts an astronaut’s ability to parent, and how it affects personal relationships — friendships, romantic relationships and beyond. Much of the information about astronaut family strain is anecdotal and can be based on reports and observations from loved ones of astronauts. The 2016 documentary “A Year in Space,” for example, follows astronaut Scott Kelly — who spent a year on the International Space Station — and includes insight into his relationships with his daughter, twin brother Mark Kelly and people he knows and loves here on Earth.

In an article for Today, astronauts Anne McClain and Nick Hague provided parenting guidance, which include things like being honest with kids about the work, creating meaningful traditions with family and being present.

“A lot of the parenting — there is no way around it — it is going to fall on the shoulders of the spouse at home,” Hague told Today. “Constant dialogue helps involve me.”

In addition to more granular information on how having an astronaut parent affects a child’s well-being, how or if tourist space travel impacts relationships and maybe even some nitty-gritty on how astronauts’ romantic relationships fare compared to non-astronaut romantic partnerships, it’ll also be important to take into perspective the whole spectrum of family. And that includes its creation.

Kellie Gerardi, a commercial astronaut and influencer who gained more mainstream attention for sharing her experience with secondary infertility, has been sharing her journey with in vitro fertilization and the road to having a second child. Her stories highlight the specific family demands required of astronauts who are pregnant, or plan to be during their work years in space — scheduling IVF and trying to plan a pregnancy, for example.

Gerardi told NPR earlier this year that her daughter, Delta, is named after a space science term Delta V, or change in velocity. According to NPR, Gerardi has a second space mission scheduled for 2026. As she’s documented on Instagram in recent posts, she’s currently pregnant.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly