Now Reading: Special economic zones for restoring American space dominance

-

01

Special economic zones for restoring American space dominance

Special economic zones for restoring American space dominance

Will China beat America in returning astronauts to the moon? We hear this question time and again. It is a perennial concern, both from a prestige and national security standpoint. But it is the wrong question. What we really need to assess is whether or not China is on track to dominate America in space.

Today, the United States has framed the next moonwalk as a “race,” with rhetoric from officials proclaiming American intent to beat China as if it were a track meet. But we are very far from making a credible attempt to even get on the field of play. The Artemis program, the NASA initiative to return Americans back to the moon for the first time since 1972, is not equipped to even offer a challenge against China’s lunar program timelines. Government officials are intent on using the Space Launch System, a program designed by “old space” primes like Boeing and Northrop Grumman, but the program is full of pork for congressional districts and has blown past its original objective of being prepared for launch by 2024.

SpaceX’s Starship program is being underutilized by the Artemis program, and is behind schedule, due to flight test failures, extended FAA investigations every time there is a test failure, and the lengthy process of undergoing environmental impact statements for increasing launch cadence across different locations. If the U.S. wants to correct the course, it needs to set up special economic zones for the space industry to sidestep regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles, and incubate in these zones the space technology companies that will build out an American presence on the moon, surpassing the simple “footstep and leave” approach that the nation adopted over half a century ago.

Beyond the moon, China is on track to beat the U.S. in dominating space entirely. In July, China performed the first ever orbital refueling between two satellites — a feat essential to SpaceX’s Starship program, but one that any American company has yet to actually achieve. And in August, headlines were made by the successful completion of an integrated landing and take off test of the nation’s Lanyue lunar lander. By all accounts, China will likely be a year or two early to their original projected moon landing date of the end of the decade.

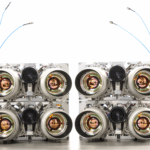

For China, there is no “race”. China does not see a race because its industrial capacity has already completely overshadowed that of the U.S.. While the U.S. currently outpaces China in launch cadence, this is almost entirely due to one single company, SpaceX. China, while not owning a space industry behemoth like SpaceX, has fostered a system of overcapacity, with 51 rocket production sites across its seven major launch companies (their space industrial ecosystem is much higher; this number only represents the seven largest space launch companies). China sees itself easily dominating space because it has the industrial capacity to rapidly build out space launch companies; an industrial capacity that the U.S. has failed to cultivate over the past half century. Not only will Chinese taikonauts beat American astronauts back to the moon, but the speed of the Chinese space program indicates that they will almost certainly lead to China building a lunar base before America, claiming the desirable locations near the lunar south pole before America and, eventually, setting foot on Mars before America.

China’s advantage in space exploration is downstream of the nation’s economic and industrial rise. To that end, we cannot understand the current state of play in space outside the context of the economic course correction the country underwent in the late 1970s. Most notable for the space industry was the implementation of Chinese special economic zones (SEZs), which created regions free from bureaucratic interference and regulatory burden. These zones rapidly increased economic development and attracted foreign investment. In 1978, China was a very poor nation near the bottom of the world as ranked by GDP; now, China is the largest manufacturing industrial economy, the largest trading nation and the largest exporter of advanced technology in part due to the influence of these SEZs.

Perhaps there is no better example than Shenzhen. In 1979, the year before Shenzhen became China’s first SEZ, the population of the small city numbered at about 30,000 inhabitants; today that number is in the tens of millions. Shenzhen is often framed as China’s “Silicon Valley” due to the massive technology hub that attracts talent from around the world, with notable companies such as Huawei Technologies, Tencent, BYD and ZTE having a large presence. The rapid pace of industrial production in Shenzhen rivals that of the hacker mindset of Silicon Valley, with “Shenzhen speed” being an official description of the area’s ability to rapidly construct giant skyscrapers in record time, completely unlike the years-long process that has crippled the West’s ability to build.

As America attempts to maintain its position as the global leader in space, there is much to learn from these examples. The current U.S. regulatory system has played a major role in holding back our nation’s space industry. In one particularly egregious example, Varda Space Industries, a company working to commercialize in-space manufacturing through the mass production of microgravity-enchanced pharmaceuticals, was heavily delayed during its first mission, with its capsule stuck in space for over eight months while Varda waited for the FAA to issue a reentry permit.

Moreover, regulations do not act in a protective or productive way when the environmental review process involved includes things like “kidnapping seals from the ocean, putting earphones on them and playing sonic boom sounds to see if they seemed upset,” which SpaceX CEO Elon Musk said his company was required to do, or “writing historical reports about the events and activities of the Mexican-American War.”

The cumulative effect of this regulatory thicket is a reduced launch cadence. This has enormous implications for the ability of the U.S. to get into space and beat China to the moon. Fewer launches means less data for testing, refining and troubleshooting the critical systems that will need to work with precision and reliability to bring American astronauts to space.

Adopting special economic zones for the companies needing to scale up their operations and increase launch cadence quickly would instantly change U.S. fortunes. SEZs would free space enterprises from the regulatory burden they are currently under to focus on the core goal of beating China to the moon.

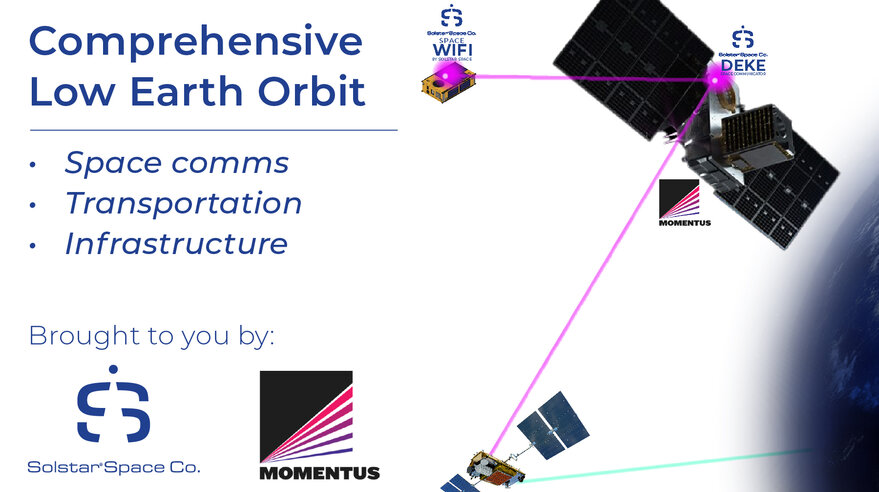

What would an SEZ to accelerate the American space industry look like? Our recent report explores the possibility of a Space Coast Compact, a pact between Texas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama to form a special economic zone built under the principles of an interstate compact. Such a partnership would provide a massive boost to getting America’s space destiny back on track. The Compact would entail massive infrastructure projects in each state, building out more spaceports as well as production sites for rockets and propellant farms. It would also mean industrial sites for companies working on the non-rocketry business cases of the space industry such as in-space manufacturing, space stations, and lunar applications.

The good news is that we have all the resources and innovation we need in America to beat China to the moon. We need only get out of our own way. By leveraging SEZs, the U.S. can reclaim the legacy of the moment that Apollo 11 touched down on the lunar surface, if only it can experiment with new regulatory structures to get there.

Tim Hwang is general counsel and a senior fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation focused on emerging technologies and national security. He is also a Senior Technology Fellow at the Institute for Progress, where he runs Macroscience. Previously, Hwang served as the general counsel and Vice President of Operations at Substack, as well as the global public policy lead for Google on artificial intelligence and machine learning. He is the author of Subprime Attention Crisis, a book about the structural vulnerabilities in the market for programmatic advertising.

Quade MacDonald is a nonresident fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation and a fellow at the Roots of Progress Institute, where he researches bottlenecks in space industrial policy and emerging space technologies.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly