Now Reading: New moon of October 2025 hides red star Antares for some lucky stargazers tomorrow

-

01

New moon of October 2025 hides red star Antares for some lucky stargazers tomorrow

New moon of October 2025 hides red star Antares for some lucky stargazers tomorrow

The new moon will see dark skies for the peak of the Orionid meteor shower, while three days later the young moon will pass in front of the red star Antares for observers in South America and the Falklands.

A new moon phase happens when the sun and moon are on the same line drawn from one celestial pole to the other. The exact moment of this month’s full moon occurs on Tuesday, Oct. 21, at 8:25 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (1225 UTC), according to the U.S. Naval Observatory.

Usually the moon appears to be above or below the sun as seen from Earth – its shadow “misses” our planet – but about twice a year the two are lined up just right so that we see a solar eclipse, the only time a new moon is visible. (The next solar eclipse is on Feb. 17, 2026, and will be visible from Antarctica). This new moon will not eclipse the sun, but the three-day-old moon will eclipse the red supergiant Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius, the Scorpion.

Occultations, like eclipses, are not rare, but being in the right place to observe them can be tricky because the shadow of the moon cast on the surface of the Earth is relatively small compared to the size of our planet. The moon, being relatively close to Earth, will have a slightly different position against the background stars depending on where one’s observing location; that difference can be as much as two degrees or four lunar diameters.

During the occultation on Oct. 24, Northern Hemisphere sky watchers in New York City, for example, which is north of the zone from which the occultation is visible, the moon will appear to be below Antares (though it will be below the horizon at that point).

This occultation will still be close to the horizon, near sunset. One larger city it is visible from is Ushuaia, Argentina. In that locale the occultation starts at 10:35 p.m. on Oct. 24, according to the International Occultation Timing Association. At that time the moon will appear to be in the low southwestern sky, about 15 degrees high. Antares will appear to disappear behind the moon’s upper right quadrant. Antares will reappear at 11:23 p.m. from the left side of the moon, which will be about 9 degrees above the horizon. Moonset is at 1:02 a.m. on Oct. 25.

In Punta Arenas, Chile, the occultation starts at 10:37 p.m. Oct. 24, and there too Antares will disappear behind the upper right quadrant of the moon and reappear on the left side at 11:28 p.m. Like in Ushuaia the moon will start the occultation about 15 degrees high and end it at about 9 degrees.

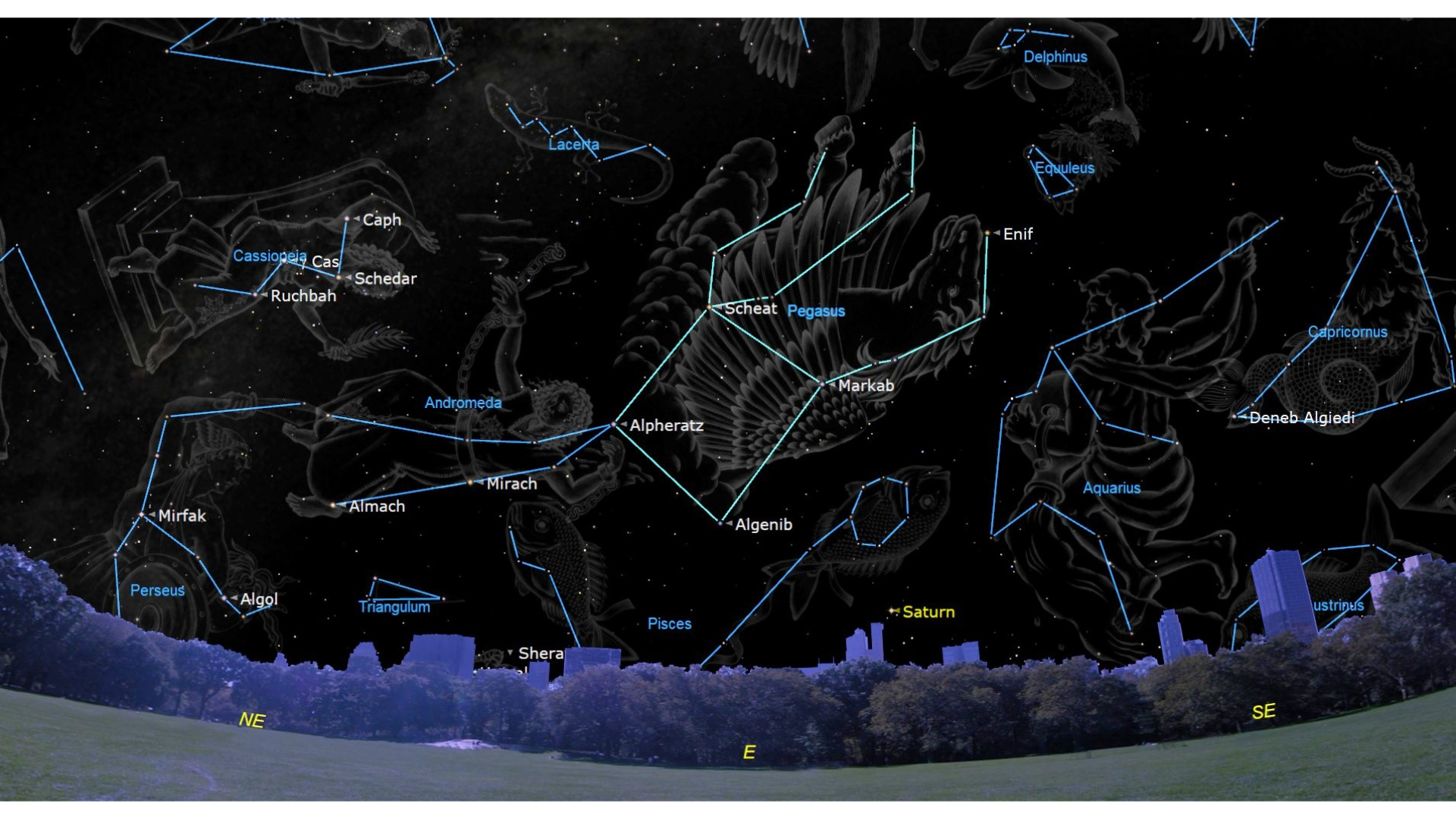

Visible planets

For those unable to see the occultation, there are still the nighttime planets in late October. At the latitude of New York City, Chicago, or Sacramento, Saturn will be the first planet visible; Saturn rises in New York at 5:54 p.m. local time in New York on October 21 and by 7:30 p.m., when the sky will be darker, it is 27 degrees above the southeastern horizon. Saturn crosses the meridian (or transits) at 10:47 p.m., and will reach an altitude of 46 degrees. The planet sets at 4:36 a.m. Oct. 22. Saturn is in Aquarius, which is a fainter constellation and that means Saturn will stand out.

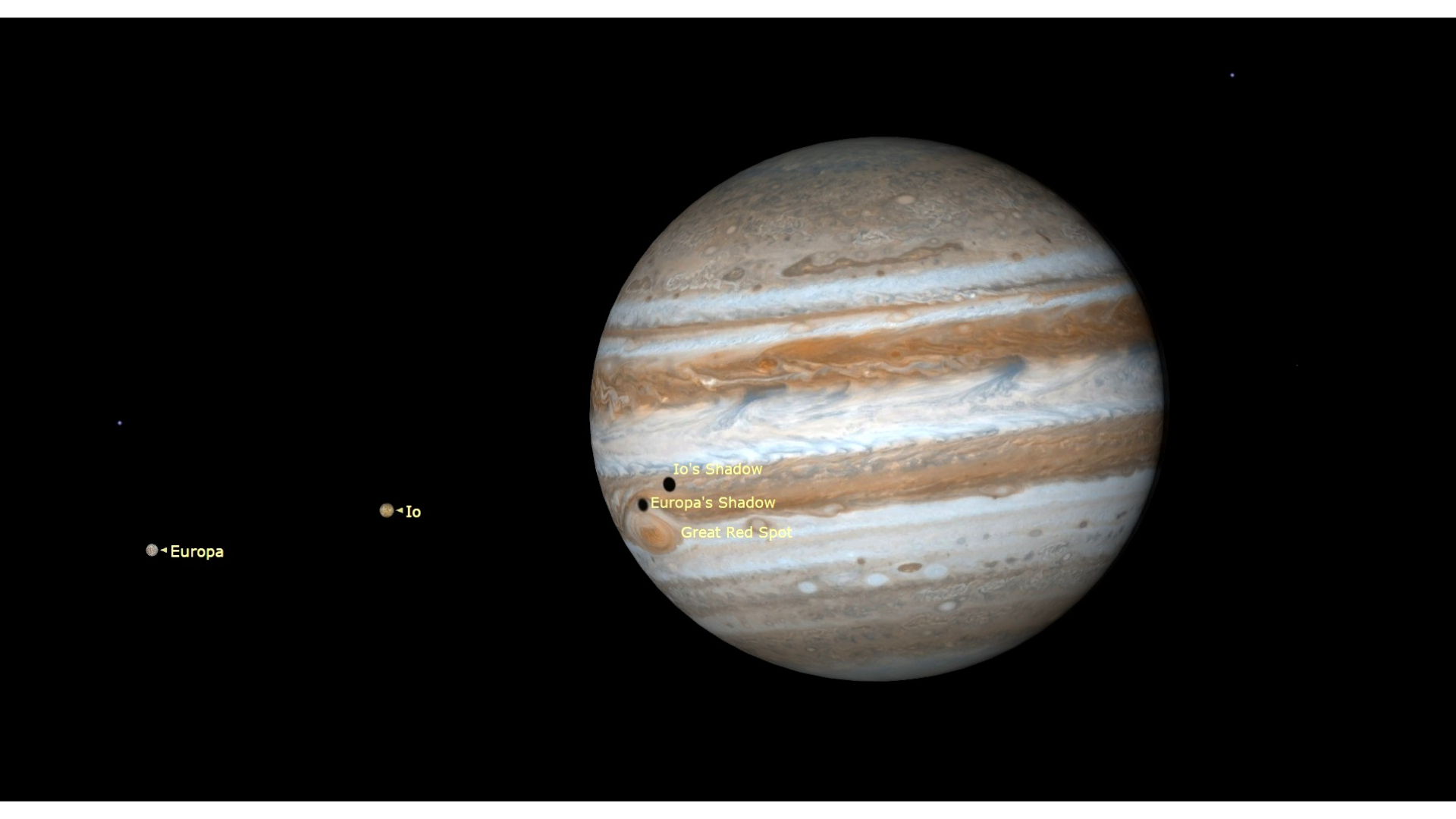

Jupiter rises at 11:16 p.m. EDT on Oct. 21, and transits at 6:37 a.m. Oct. 22., and reaches an altitude of 71 degrees. Jupiter will be in the constellation Gemini, the twins, and will appear just below and to the right of Pollux, Gemini’s second-brightest star. One can tell Jupiter from Pollux because planets tend to shine with steady light, whereas stars will twinkle.

Venus will rise just before dawn, at 5:37 a.m. Oct. 22. Venus is the third brightest object in the sky after the sun and moon, will be visible until just before sunrise at 7:15 a.m., though by 7 a.m. it will lonely be about 14 degrees above the eastern horizon (a good observational exercise is to see how close to sunrise one can still pick out Venus against the sky before it fades against the background).

Further south, Saturn, Jupiter and Venus will all appear higher in the sky. From Miami, Saturn rises at 5:14 p.m. local time. Sunset in Miami is at 6:48 p.m., and by about 7:30 p.m. Saturn is 29 degrees high in the east. Jupiter rises at 12:17 a.m. Oct. 22, and transits at 7:02 a.m. at an altitude of 86 degrees. Venus rises at 6:01 a.m.; by 7 a.m. it is 13 degrees high in the east. (Sunrise is at 7:24 a.m.)

In the Southern Hemisphere, the days are getting longer as summer approaches, and sunsets are later. From Santiago, Chile, Saturn rises at 5:17 p.m., during the day; sunset is at 8:00 p.m. local time. By 8:30 p.m. the sky is getting dark enough that Saturn will be easier to see, and the planet will be about 38 degrees high in the northeast. Saturn transits at 11:30 p.m. and reaches an altitude of 60 degrees above the northern horizon. Jupiter follows at 2:21 a.m. local time on Oct. 22., and transits at 7:25 a.m., though that is after local sunrise which is at 6:52 a.m. But by 6 a.m. Jupiter will be about 31 degrees high in the northern sky. Venus rises in Santiago at 6:09 a.m., but it will be so close to the horizon – only 4 degrees high by 6:30 a.m. – that it won’t be visible against the glare of the sun.

Unlike in the Northern Hemisphere, Mars and Mercury will be more visible in the Southern Hemisphere mid-latitudes, where they are not lost in the light from sunset. From Santiago, on the evening of Oct. 21, local sunset is at 8:00 p.m. and by 8:30 at Mercury will still be 15 degrees above the western horizon, with Mars just below and to the right of Mercury. By 8:45 both planets are about 12 degrees high, and the sky is getting dark enough to see them.

Stars and constellations

From mid-northern latitudes in late October, the summer constellations of the zodiac – Sagittarius, Ophiuchus and Scorpio – are exiting the sky to make way for the fall stars. By 8 p.m. The Summer Triangle, consisting of Vega, Altair and Deneb is near the zenith; Vega is to the right (westward) and Altair towards the horizon, just over halfway to the zenith at 53 degrees.

As one looks eastward, to the left and towards the horizon, one encounters the Great Square, above and to the left of Saturn. The Great Square is an asterism made of the stars of constellations: Pegasus and Andromeda. At 8 p.m. the Square looks as though it is standing on one corner. The rightmost three stars are the wings of Pegasus, while the left corner is Andromeda’s head. If one looks downwards and to the left one encounters a curved line of four stars, which is Andromeda’s body. From there one can turn further left, to the north and east, and see a “W” shape of stars, which is Cassiopeia, the Queen (and according to legend Andromeda’s mother). If one follows the curve of stars describing Andromeda, and continues towards the horizon, one finds Perseus, the hero who saved Andromeda from a sea monster, riding Pegasus to her rescue.

Turning northwards, one will see the Big Dipper close to the horizon, the dipper appearing right side up (the bowl facing upwards). One can use the pointers, stars named Dubhe and Merak on the right side – the “front” of the bowl — to find Polaris, the pole star. Dubhe is the uppermost star; Merak is below it. Polaris is the brightest star in Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, and if the sky is dark and one is away from city lights the curve of the Little Dipper’s handle is easier to see.

As the night progresses and one looks to the northeast, one can see Capella; in mid-northern latitudes the star rises during the late afternoon on Oct. 21 (at 5:49 p.m. in New York) but by 10 p.m. is high enough – about 26 degrees — to see easily. Capella is the brightest star in Auriga, the Charioteer.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the sky gets truly dark by about 9 p.m. Observers from the latitude of Santiago, Chile, Cape Town, or Melbourne, Australia will see the Southern Cross low in the south-southwest, with its brightest star Acrux just 13 degrees above the horizon. If one follows the crossbar of the cross upwards one sees Hadar and Rigil Kentaurus, Hadar being the star closer to the horizon.

Turning left and looking southeast, one will see Achernar, the end of Eridanus the River, about 41 degrees high. In areas with less interference from city lights, one can see some fainter stars to the left of Achernar; this is the constellation called the Phoenix; the “backbone” of the bird shape is a line of five fainter stars running roughly north-south.

If one looks from the Southern Cross, towards the west, one can see Antares, the heart of Scorpio, about 25 degrees high. Scorpio is “upside down” – the claws of the Scorpion point to the horizon, and the tail curves toward the zenith, making a fishhook shape that ends about 45 degrees above the horizon.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Panasonic Leica Summilux DG 15mm f/1.7 ASPH review

02Panasonic Leica Summilux DG 15mm f/1.7 ASPH review -

03Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

03Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

04How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

04How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

05And Thus Begins A New Year For Life On Earth

05And Thus Begins A New Year For Life On Earth -

06Astronomy Activation Ambassadors: A New Era

06Astronomy Activation Ambassadors: A New Era -

07SpaceX launch surge helps set new global launch record in 2024