Now Reading: Why the moon is not the South China Sea: reframing lunar space ahead of the next ‘race’

-

01

Why the moon is not the South China Sea: reframing lunar space ahead of the next ‘race’

Why the moon is not the South China Sea: reframing lunar space ahead of the next ‘race’

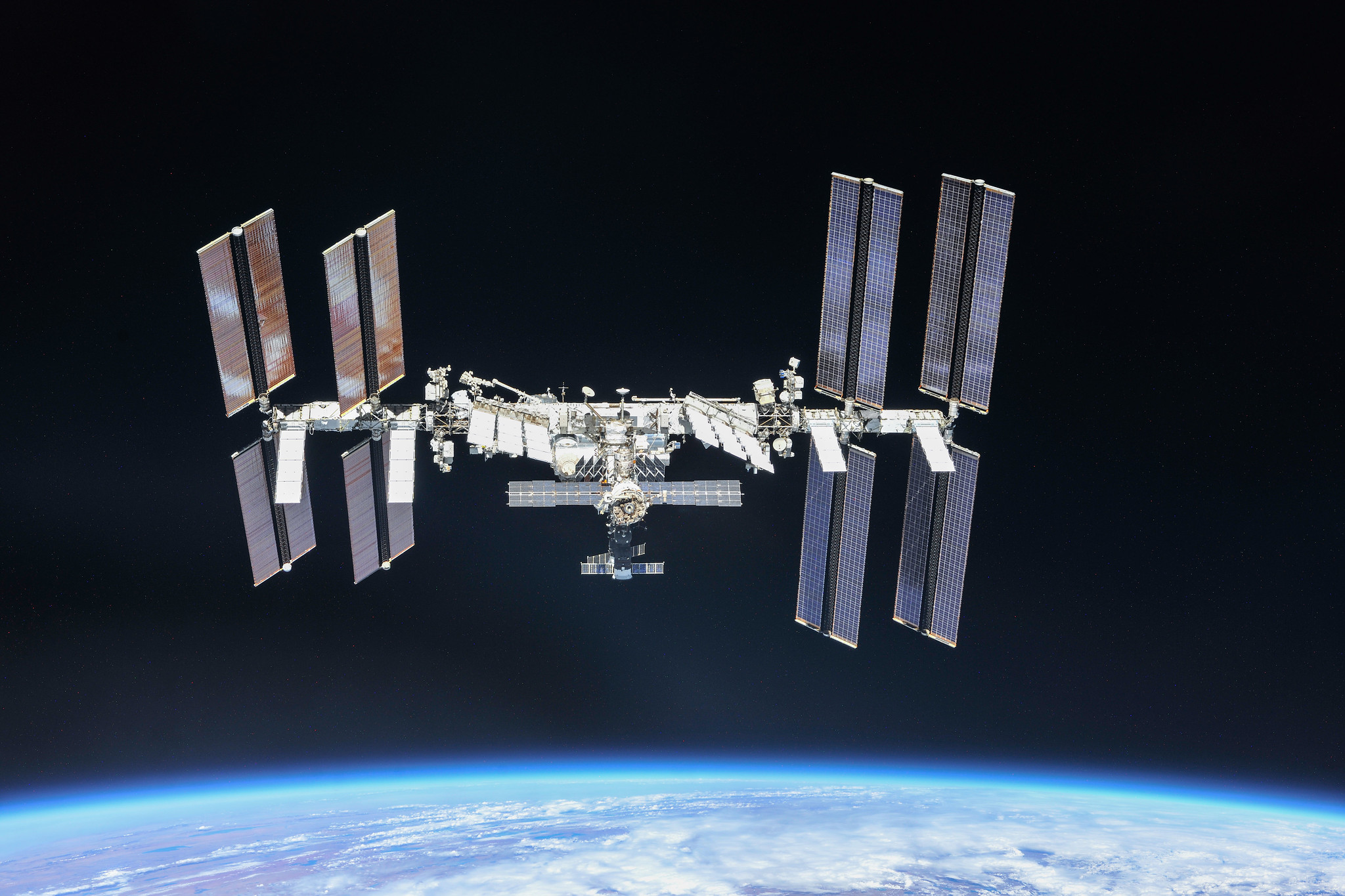

As the world watches the push for crewed lunar missions, it is tempting to frame the unfolding dynamic between the United States and China as a modern-day space race, with the lunar surface as the stage for a sovereignty contest. But equating the moon with contested maritime zones like the South China Sea, as a recent SpaceNews opinion article did, is a flawed analogy — one that risks importing Earth’s territorial rivalries into a domain meant to transcend them.

First, the analogy to the South China Sea misunderstands the legal and normative context of lunar exploration. That marine region involves complex historical claims of sovereignty and maritime rights. The moon, by contrast, is governed by the Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967, whose Article II explicitly prohibits national appropriation of celestial bodies by “claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” Unlike the South China Sea, the moon resides under an established international legal framework that forbids sovereignty claims. A Chinese taikonaut planting a flag, as a symbolic act, would not legally translate into sovereignty any more than the planting of the U.S. flag by the Apollo 11 crew did.

Second, framing a “race” to the moon as purely adversarial ignores how much the context has changed since the Apollo era. Apollo was a bilateral Cold War contest between two isolated blocs. Today’s lunar ambitions — under initiatives such as the Artemis Program, China’s International Lunar Research Station concept, India’s Chandrayaan program and growing private-sector participation — are inherently more global and cooperative in nature. The real challenge lies not in planting flags first, but in managing access, safety zones and resource extraction in a crowded lunar environment. Overemphasizing national competition risks hardening lines and undermining the very norms that drive collaboration in space.

Third, the proposed U.S. strategy of deploying a Congressional resolution, a United Nations resolution, and closed‐door diplomacy with Beijing presumes that reaffirmation of non-sovereignty will materially deter China. In fact, China is already a party to the OST and has publicly affirmed its commitment to the peaceful use of outer space. A move that demands performative proclamations may instead invite nationalist counter-narratives and heighten rivalry — thereby feeding the very competition the strategy claims to prevent.

Finally, to equate China’s “law-fare” behavior in the South China Sea with an inevitable lunar sequel errs on privilege of cynicism. Both China and the U.S. are deeply enmeshed in shared orbital data systems, cross-national rescue obligations (see the Rescue Agreement of 1968) and collaborative satellite networks. Neither benefits from destabilizing the legal order that enables their activities. In other words, international interdependence in space is far stronger than in maritime territorial contests — and this interdependence can act as a stabilising force rather than a flashpoint.

If there is indeed a next “space race,” let it be a race not to dominance but to restraint, transparency and shared stewardship. The lesson of Apollo was not conquest, but perspective: that when seen from the lunar surface, Earth is one. To lose that mindset would be humanity’s greatest misstep.

Rich Costa is a space launch security operations expert with nine years at Vandenberg Space Force Base and a lifelong interest in humanity’s future in space.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly