Now Reading: ‘House of Dynamite’ and where U.S. missile defense goes from here

-

01

‘House of Dynamite’ and where U.S. missile defense goes from here

‘House of Dynamite’ and where U.S. missile defense goes from here

A new shock-and-awe movie might sharpen public concern about American vulnerability to nuclear attack and defense against it. The fictional ”House of Dynamite” shows United States leaders trying to respond to a single bolt-from-the-blue strike. Missile defense fails. The movie could spur real-world interest in better protection.

In ”House of Dynamite”, an intercontinental ballistic missile launched from the Pacific streaks toward America. Leaders have only 20 or so minutes to make life-or-death decisions. U.S. ground-based interceptors seek to hit and pulverize the reentry vehicle in space but miss. The impatient head of the U.S. Strategic Command favors a preemptive strike against presumed but unknown adversaries. The President is poorly informed, and the Secretary of Defense erratic.

The film could have political impact, as did two legendary ones from the 1960s. In the satirical classic ”Dr. Strangelove”, a deranged U.S. general orders a nuclear attack on the USSR. In ”Fail Safe”, a technical glitch sends a bomber squadron toward Moscow. In both cases, bombers could not be recalled.

All three movies reveal inadequate aerospace defenses against intercontinental nuclear forces. ”House of Dynamite” and a recent thought-provoking book, ”Nuclear War”, by Annie Jacobson, highlight missile defense limitations.

In 1983, President Reagan called for a futuristic Strategic Defense Initiative that might render nuclear weapons “impotent and obsolete.” His vision required huge advances in technology. Years later, the U.S. took a modest step forward by deploying a ground-based midcourse defense (GMD) program. Its 44 nonnuclear interceptors are designed to hit re-entry vehicles in space flight. Even North Korea might be capable of sending decoys into space that nonnuclear interceptors could have difficulty distinguishing from armed reentry vehicles. Mixed test results of currently deployed GMD technology raise concerns.

If it were effective, a limited missile defense could protect against a small-scale accidental, unauthorized, or purposeful nuclear attack. To address this threat, in the 1980s then-Chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee Sam Nunn proposed an Accidental Launch Protection System. Today’s GMD system is sized for this role. A larger system to defend against major attacks may make sense as technologies improve. But costs could be significant, and adversaries might try to respond by adding offensive missiles.

An upgraded nonnuclear ground-based interceptor system coupled with a new generation of space-based sensors is likely to be more effective than GMD today. This option deserves priority examination.

A second nonnuclear technology — space-based interceptors — holds promise. They would attack ballistic missiles in the boost phase, when they burn hot and are easy to detect and home in on. Technology for this might be in sight but require more development. To destroy a single intercontinental ballistic missile, many hundreds of interceptors based in low earth orbit may be required for one or more to be close enough. The overwhelming portion of the constellation would not be in the field of view.

Space-based interceptors would have to be fired soon after detection of a missile launch. Since the boost phase lasts only several minutes, the short time horizon could stress a decision-making process. Also, an opponent might try to blow a hole in the constellation with anti-satellite weapons.

If nonnuclear technologies are not sufficient, there could be calls to revive an earlier nuclear-based concept. This would involve ground-based interceptors armed with low-yield nuclear weapons. These interceptors would not need to distinguish decoys from armed reentry vehicles; all would be destroyed.

In the 1970s, the U.S. briefly fielded a small, nuclear-armed Safeguard missile defense system. It lacked precision guidance and stirred controversy. It was soon abandoned. Returning now to an approach based on nuclear-armed defenses could spark public opposition.

Upgraded nonnuclear ground-based interceptors coupled with a new generation of space-based sensors are likely to be more effective than today’s GMD system. An even more robust missile defense might be layered, involving space-based, nuclear or other technologies. These options deserve priority examination.

In ”House of Dynamite,” a major American city perishes. The film might perform a public service by helping to reinvigorate interest in assessing possibilities for homeland defense against missile threats.

William Courtney is an adjunct senior fellow at RAND and professor of policy analysis at the RAND School of Public Policy. He was deputy negotiator in the U.S.-Soviet Defense and Space Talks (on missile defense) and ambassador in negotiations to implement the Threshold Test Ban Treaty.

Peter A. Wilson currently teaches a course on the history of military technological innovation for the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. He is an adjunct senior national security researcher at RAND.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Panasonic Leica Summilux DG 15mm f/1.7 ASPH review

02Panasonic Leica Summilux DG 15mm f/1.7 ASPH review -

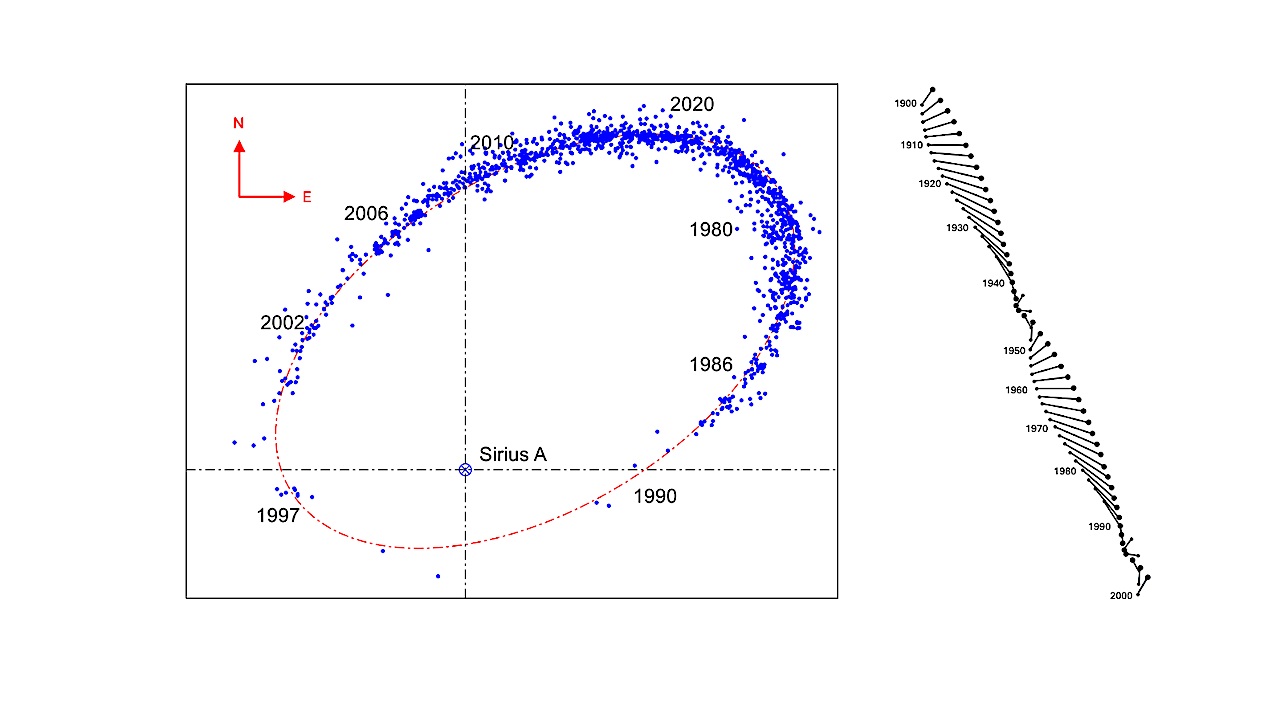

03Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

03Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

04How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

04How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

05And Thus Begins A New Year For Life On Earth

05And Thus Begins A New Year For Life On Earth -

06Astronomy Activation Ambassadors: A New Era

06Astronomy Activation Ambassadors: A New Era -

07SpaceX launch surge helps set new global launch record in 2024