Now Reading: Hidden ocean on Enceladus might be stable enough for life

-

01

Hidden ocean on Enceladus might be stable enough for life

Hidden ocean on Enceladus might be stable enough for life

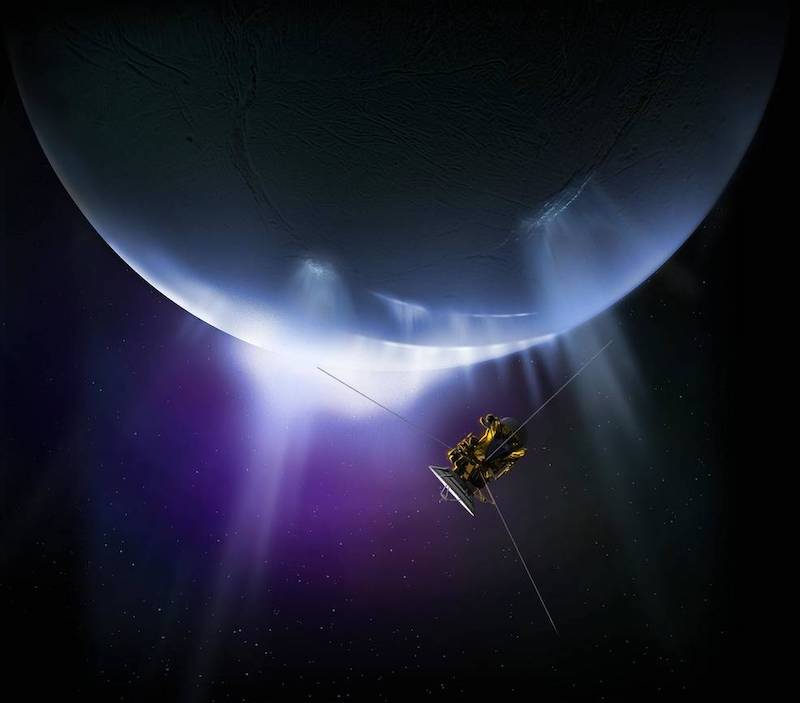

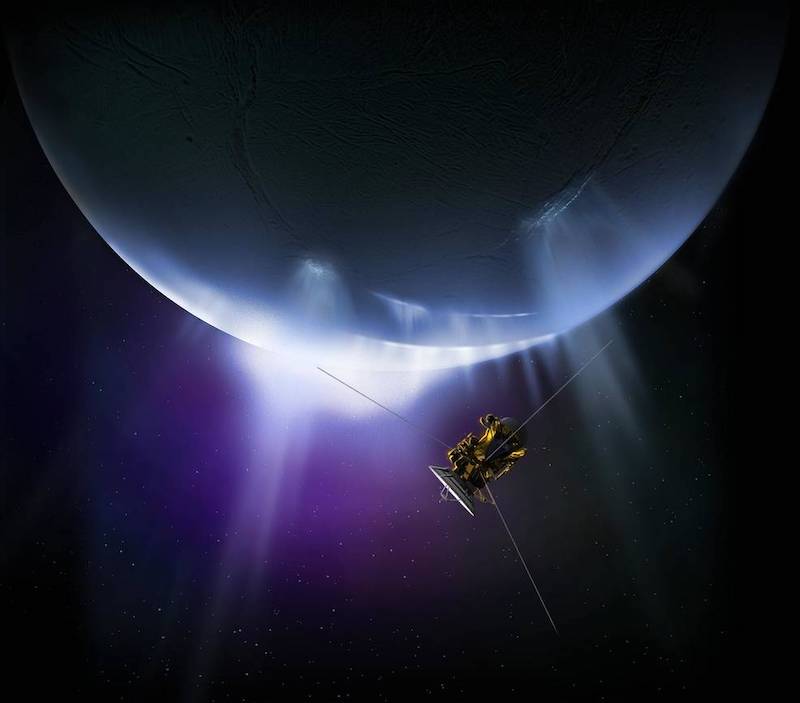

- Saturn’s moon Enceladus has a salty, global subsurface ocean similar to Earth’s oceans. Is it habitable? Could there actually be life there?

- Enceladus’ ocean is likely stable enough to support life, a new analysis of Cassini data showed.

- Scientists measured heat flow at the moon’s north pole for the 1st time. This heat loss at both poles is evidence that the ocean is stable over long geological time periods.

A stable, habitable ocean on Enceladus?

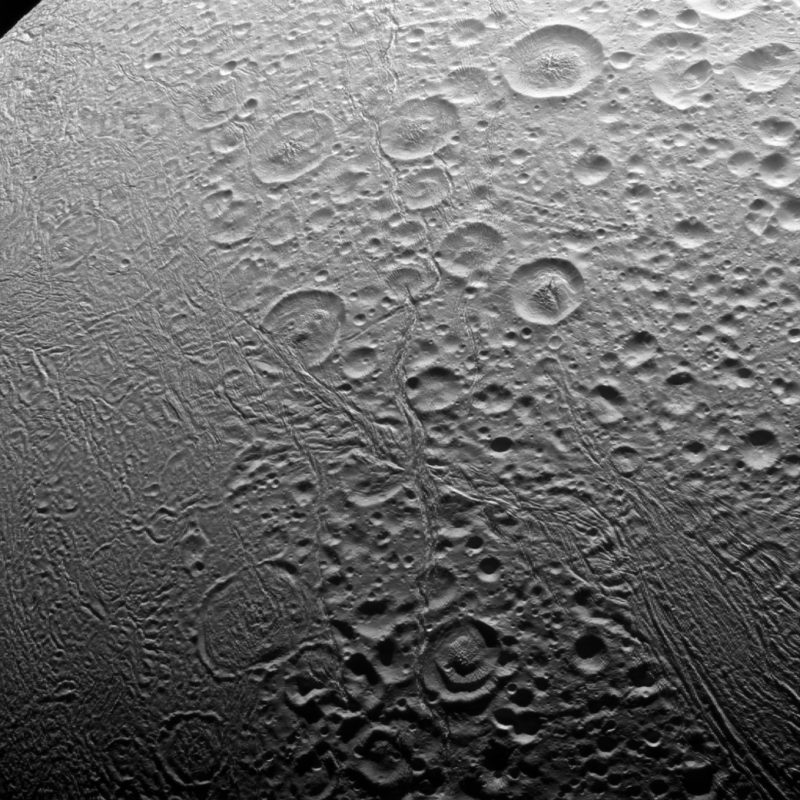

Scientists have found yet more evidence that the subsurface ocean on Saturn’s moon Enceladus might be habitable. Researchers from the University of Oxford, Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Texas and the Planetary Science Institute (PSI) in Arizona said on November 10, 2025, that they have confirmed heat flow at the moon’s north pole, not just the south pole as first thought. This indicates that Enceladus is generating a lot more heat inside than previously known. This suggests the ocean has been stable over the long term geologically. It’s an exciting new finding hinting at how this alien ocean just might be home for some form of life.

The researchers used data from the now-finished Cassini mission for their new study.

Previously, scientists thought heat was escaping into space only from Enceladus’ south pole. That is where the huge water vapor plumes erupt from long cracks in the icy surface called tiger stripes. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft previously flew through the plumes and sampled them to analyze their composition.

The intriguing new peer-reviewed results were published in Science Advances on November 7, 2025.

Heat loss at Enceladus’ north pole

Scientists have thought that the north pole on Enceladus was much less geologically active than its south pole. That made sense, since it’s at the south pole where the tiger stripes and plumes are located. And scientists had only measured heat loss at the south pole.

But now, it seems there might be some geological activity at the north pole after all. The researchers compared Cassini observations of the north polar region in deep winter (in 2005) and summer (in 2015). They then measured how much energy Enceladus loses from its “warm” subsurface ocean (32 degrees Fahrenheit or 0 degrees Celsius) as heat travels through the icy outer shell to the surface (–370 degrees F, or -223 degrees C) and then radiates into space.

Lead author Georgina Miles at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and a visiting scientist at the Department of Physics, University of Oxford, said:

Eking out the subtle surface temperature variations caused by Enceladus’ conductive heat flow from its daily and seasonal temperature changes was a challenge, and was only made possible by Cassini’s extended missions.

North pole warmer than expected

Researchers modeled the expected surface temperatures during the polar night and compared them with infrared observations from the Cassini Composite InfraRed Spectrometer (CIRS). And – surprise – they found the surface at the north pole was about 7 Kelvin warmer than expected. According to the researchers, only heat leaking from the ocean below could explain that.

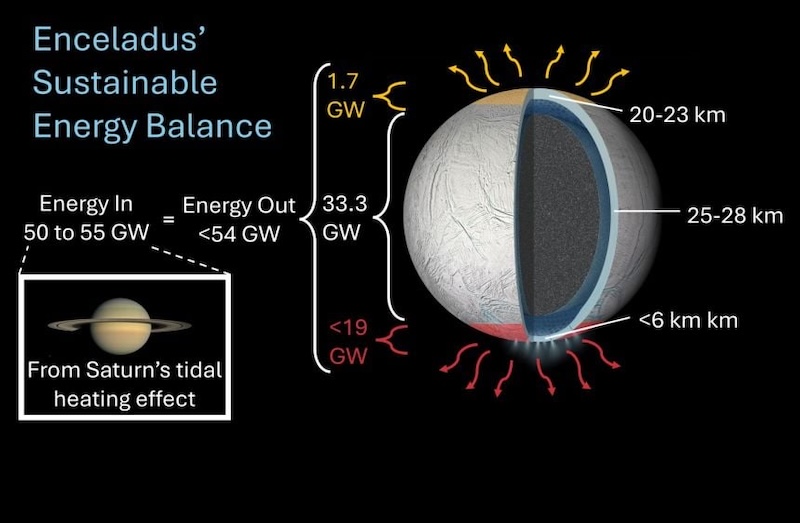

The researchers measured the heat flow at 46 ± 4 milliwatts per square meter. That’s equivalent to 2/3 of the heat loss (per unit area) through Earth’s continental crusts. This is a total heat loss of 35 gigawatts for all of Enceladus. That equals 66 million solar panels (with an output of 530 watts) or 10,500 wind turbines (with an output of 3.4 megawatts).

The results also show the ice shell thickness at the north pole to be about 12-19 miles (20-30 km). This is consistent with previous models.

Interestingly, another team of researchers said in 2020 that they found evidence for plumes at Enceladus’ north pole, as well. They are thought to be smaller and weaker than the ones at the south pole. But if confirmed, they would fit with the new evidence for heat leaking from the ocean at the north pole, through cracks in the ice crust.

NEW: Latest findings from NASA’s Cassini mission show that Enceladus – one of Saturn’s moons and a top contender for extra-terrestrial life – is losing heat from both poles, suggesting it could stay stable enough for life to form.Read more ??

— University of Oxford (@ox.ac.uk) 2025-11-10T16:10:19.457171907Z

Evidence for a stable ocean on Enceladus

The researchers then combined the heat loss at both poles for a total of about 54 gigawatts. Notably, that is close to what models predicted for heat input from tidal forces in the ocean. Why is that significant? It means there is a balance between heat production and heat loss. That would allow the subsurface ocean to remain stable for a long time.

The tidal heating – caused by Saturn’s gravity tugging on Enceladus – would maintain this balance. This is important. If the ocean doesn’t gain enough energy, it would eventually freeze solid. If there’s too much energy, however, then that could alter the chemistry of the ocean, perhaps making it less habitable.

Enceladus: An abode of life?

The evidence has mounted in recent years that Enceladus’ ocean is potentially habitable. Cassini found all of the necessary ingredients in the water vapor plumes, including complex organics and phosphorous. The ocean is also salty, but not too salty. There is also evidence for hydrothermal activity – hydrothermal vents – on the ocean floor, much like in Earth’s oceans.

But more study is needed, including from future missions going back to Enceladus. And as with Cassini, it can take many years to go through all of the data. As Miles noted:

Our study highlights the need for long-term missions to ocean worlds that may harbor life, and the fact the data might not reveal all its secrets until decades after it has been obtained.

Bottom line: The subsurface ocean on Enceladus is stable enough for life, a new study of data from the Cassini mission suggests. Heat flow at both poles provides the clues.

Source: Endogenic heat at Enceladus’ north pole

Read more: Do the organics in Enceladus’ ocean point to habitability?

Read more: Enceladus’ ocean even more habitable than thought

The post Hidden ocean on Enceladus might be stable enough for life first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

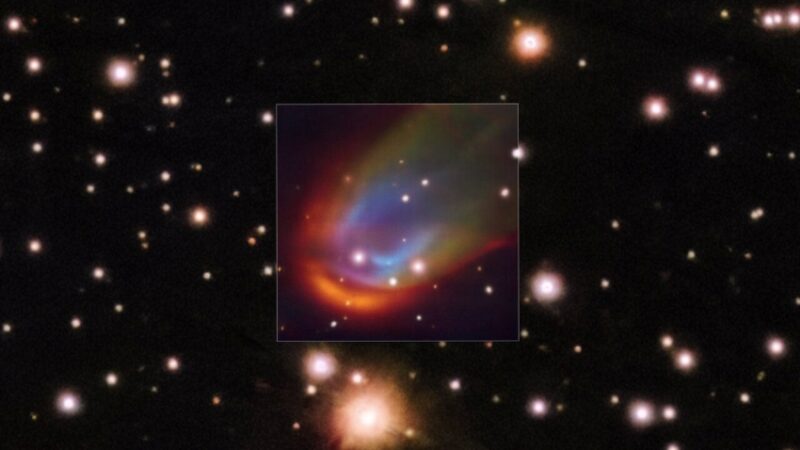

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly