Now Reading: ESA pinpoints 3I/ATLAS’s path with data from Mars

-

01

ESA pinpoints 3I/ATLAS’s path with data from Mars

ESA pinpoints 3I/ATLAS’s path with data from Mars

14/11/2025

1186 views

6 likes

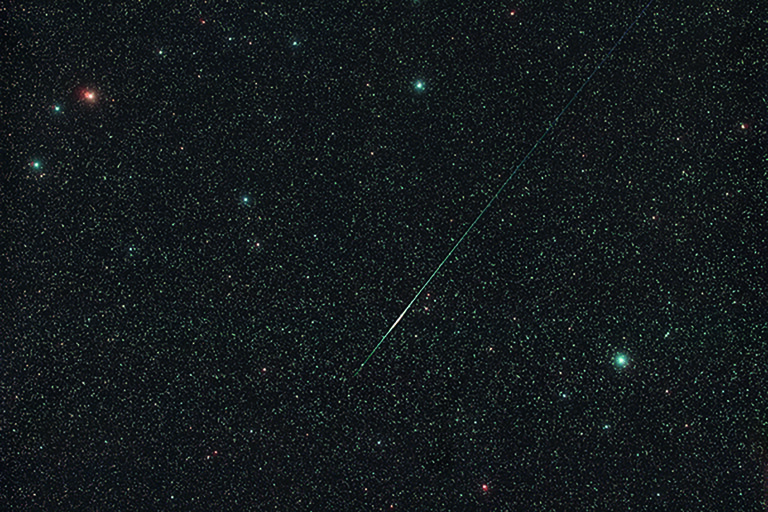

Since comet 3I/ATLAS, the third known interstellar object, was discovered on 1 July 2025, astronomers worldwide have worked to predict its trajectory. ESA has now improved the comet’s predicted location by a factor of 10, thanks to the innovative use of observation data from our ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) spacecraft orbiting Mars.

By being able to use Mars-based data for an unusual observation, we learned more about the interstellar comet’s path through our Solar System in a valuable test case for planetary defence, even though 3I/ATLAS does not pose any danger.

New angle from Mars unlocks precision

Until September, figuring out the location and trajectory of 3I/ATLAS relied on Earth-based telescopes. Then between 1 and 7 October, ESA’s ExoMars TGO turned its eyes towards the interstellar comet from its orbit around Mars. The comet passed relatively close to Mars, approaching to about 29 million km during its closest phase on 3 October (more on the observations).

The Mars probe got about ten times closer to 3I/ATLAS than telescopes on Earth and it observed the comet from a new viewing angle. The triangulation of its data with data from Earth helped to make the comet’s predicted path much more accurate.

While the scientists initially anticipated a modest improvement, the result was an impressive ten-fold leap in accuracy, reducing the uncertainty of the object’s location.

Because 3I/ATLAS is passing through our Solar System fast, travelling with speeds up to 250 000 km/h, it will soon vanish into interstellar space, never to return. The improved trajectory allows astronomers to aim their instruments with confidence, enabling more detailed science of the third interstellar object ever detected.

From Mars data to accurate predictions

It was a challenge to use the Mars orbiter’s data to refine an interstellar comet’s path through space. The CaSSIS instrument was designed to point towards the nearby Martian surface and look at it in high resolution. This time, the camera was aimed at the skies above Mars to catch the tiny, distant 3I/ATLAS sweeping by across a starry backdrop.

The astronomers in the planetary defence team at ESA’s Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre, used to determining the trajectories of asteroids and comets, had to account for the spacecraft’s special location.

Usually, trajectory observations are made from fixed observatories on Earth, and occasionally from a spacecraft in near-Earth orbit, like the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope or NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. The astronomers are well-practiced in considering their location as they determine the future locations of objects, called ephemeris.

This time, the ephemeris of 3I/ATLAS, and in particular the prediction’s precision, depended on accounting for the exact location of ExoMars TGO: at Mars and in a fast orbit around it. It required working together in a combined effort by several ESA teams and partners, from flight dynamics to science and instrument teams. Challenges and subtleties that are usually negligible, had to be tackled to reduce the margins as much as possible, in order to achieve the highest accuracy possible.

The resulting data on comet 3I/ATLAS is the first time that astrometric measurements from a spacecraft orbiting another planet have been officially submitted and accepted into the Minor Planet Center (MPC) database. The database acts as a central clearing house for asteroid and comet observations, streamlining data collected by different telescopes, radar stations and spacecraft.

A test case for planetary defence

Even though 3I/ATLAS poses no threat, it was a valuable exercise for planetary defence. ESA routinely monitors near-Earth asteroids and comets, calculating orbits to provide warnings if required. As this ‘rehearsal’ with 3I/ATLAS shows, it can be useful to triangulate data from Earth with observations from a second location in space. A spacecraft may also happen to be closer to an object, adding even more value.

Practicing with spacecraft data beyond Earth orbit hones important skills and demonstrates the value of leveraging resources not designed for asteroid detection, boosting readiness in case of a threat.

What’s next?

The comet is currently being observed with our Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice). Though Juice is farther from 3I/ATLAS than the Mars orbiters were last month, it is seeing the comet just after its closest approach to the Sun, when it is in a more active state. We don’t expect to receive data from Juice’s observations until February 2026 – find out why in our FAQs.

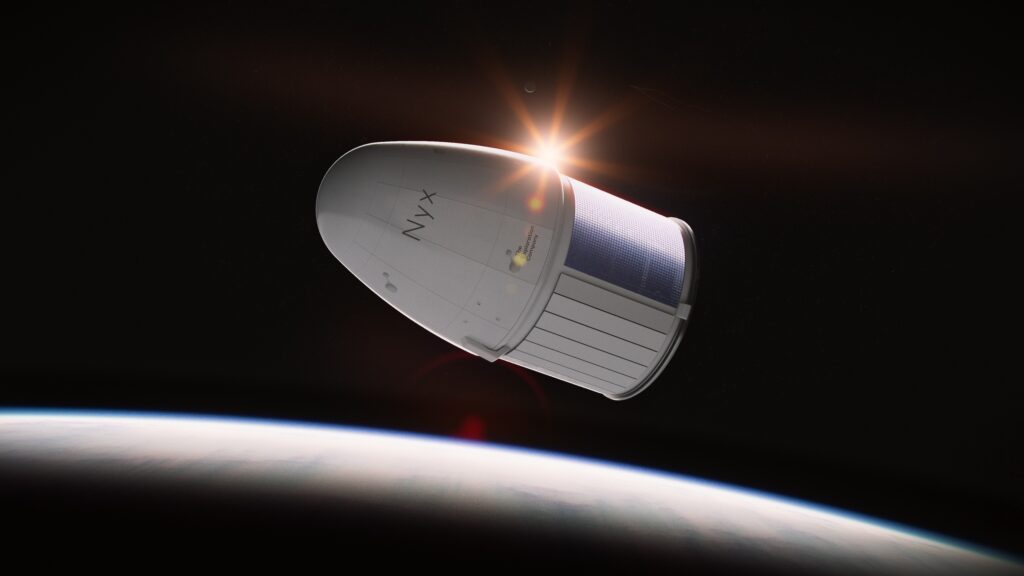

We should not only count on spacecraft hopefully being in the vicinity of hard-to-observe objects that might pose a threat. Therefore, ESA is preparing the Neomir mission, to cover the known blind spot that the Sun causes for asteroid observations, its bright glow outshining the faint glimmer of an asteroid or comet. Neomir will be located between the Sun and Earth to detect near-Earth objects coming from the Sun’s direction at least three weeks in advance of potential Earth impact.

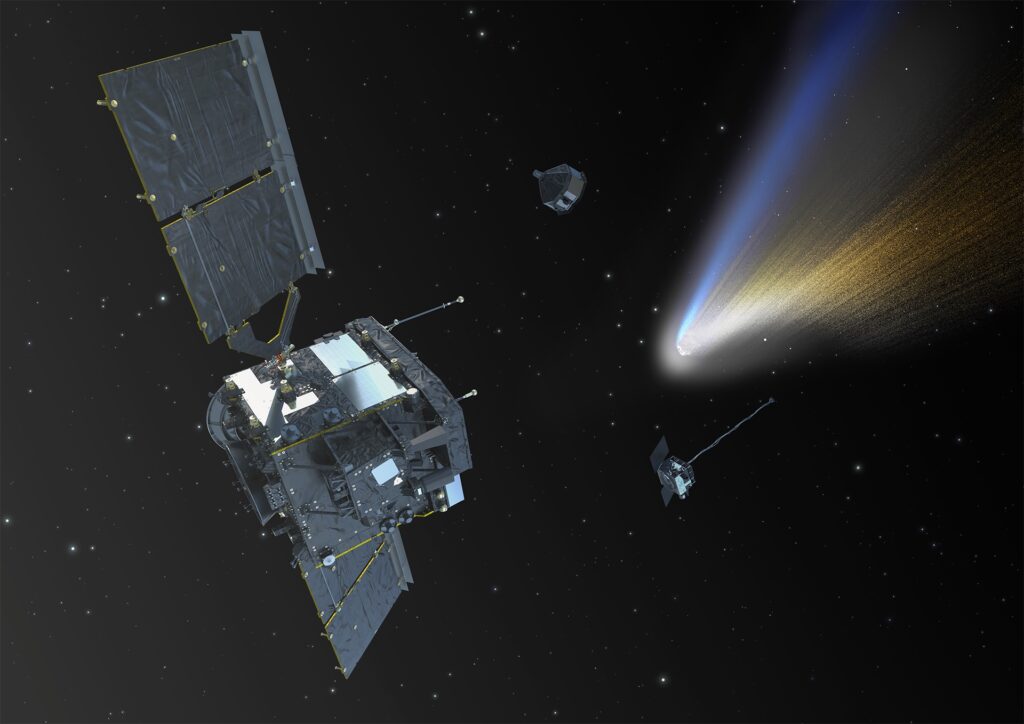

Icy wanderers such as 3I/ATLAS offer a rare, tangible connection to the broader galaxy. To actually visit one would connect humankind with the Universe on a far greater scale. ESA is preparing the Comet Interceptor mission that will learn more about a comet – with luck, it just might be an interstellar one.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly