Now Reading: Reimagining space stations for the commercial age

-

01

Reimagining space stations for the commercial age

Reimagining space stations for the commercial age

In this episode of Space Minds, host Mike Gruss sits down with Marshall Smith, CEO of Starlab Space for a fireside chat at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center, the next installment of the Center’s Discovery Series.

In the fireside chat, they explored how today’s commercial space pioneers are turning concepts once rooted in science fiction into operational reality.

Smith reflects on his path from NASA engineer to leading the development of a next-generation commercial space station—one designed for science, manufacturing, and a future where private industry drives a sustainable economy in low Earth orbit. From market demand to design philosophy to the race toward a 2029 launch, Smith explains why he believes continuous human presence in space is essential, and how innovations in microgravity research and AI-driven operations could redefine what’s possible both on orbit and on Earth.

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Time Markers

00:00 – Episode introduction

00:27 – Setting the stage

02:31 – First fell in love with space

04:01 – The moment commercial stations started to feel feasible

05:11 – Why commercial space still feels far away

06:36 – What Starlab actually is: scale, purpose & design

09:14 – Designing a space station with Hilton & Journey

11:49 – What must happen between now and the 2029 launch

15:32 – Should there be a continuous human presence in space?

18:15 – Prestige, perception & ending continuous presence

18:51 – The market for commercial space stations

19:09 – How many Starlabs could exist?

20:42 – Government, universities & private investment roles

22:27 – Keeping the LEO ecosystem healthy

22:56 – How NASA can best support commercial LEO destinations

25:04 – Looking ahead to 2030: what success looks like

26:10 – How AI will transform operations in space

Transcript – Marshall Smith Conversation

This transcript has been edited-for-clarity.

Mike Gruss – I’ve been a journalist covering space about 13 years, and one thing I’m always struck by is the role of science fiction in the space industry. Two of the titans in space right now, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, have each been honored with the Arthur C. Clarke Innovation Award, which recognizes achievements in satellite communication, space and technology. Each of them has talked about the role that science fiction and Clarke’s work played in their own lives.

I mention this because I think we’re at a moment now where, when we talk about advances in space, we’re often talking about some of the very same technology that first came into public consciousness via popular culture — whether that’s science fiction books or movies or comic books. And I say that, and it’s not a completely fair assessment, and it plays on a kind of cliché, right?

But tonight we’re going to talk with companies that have long been working on making these technologies that felt decades away into something real. Starlab is developing a large, single-module, three-floor space station that’s expected to launch in 2029. Astrobotic is developing a large lunar lander carrying a commercial rover that is expected to launch no earlier than mid-’26. Stoke is developing its Nova rocket, a medium-lift vehicle whose first and second stages are both designed for reuse. It’s also raised $510 million to fund operations for these first launches. Apex is working to scale satellite production for both national security missions and commercial constellations. And the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab is working on a car-size octocopter to explore the surface of a distant world.

For this fireside chat tonight, I’d like to invite Marshall Smith, the CEO of Starlab Space, to the stage. He guides the company’s vision, strategy, and success. Previously, he worked at NASA for 37 years. Marshall, come on. Hey. Thanks. Appreciate you doing this.

So I want to start — tell me about that time when you first fell in love with space. When you said, “Hey, this is cool, and this is something that I want to be a part of.” Was it something that was science-fiction related, or was it something else?

Marshall Smith – It actually was. You know, I grew up an Air Force brat. My dad would go all over. I lived on air bases, and I was really involved in aviation — just being out on the playground and watching these planes fly right over top of the playground, everybody looking up. And, you know, “Wow, I want to do that one day.”

And of course, I’m old, so I got to watch some of the late Apollo missions live. I remember them, and just really being excited about it, carrying around my Apollo rocket. And then, of course, science fiction on TV, and getting involved in all of that. And it just became something where I thought, “You know, this is something that we could really make happen.”

So I joined NASA. I was an intern. I went through co-op programs, as we called it back then. And I started off in airplanes, because that was my first love. But I eventually moved into Earth satellite missions, Mars missions, and then got involved in Ares 1-X, which was the first rocket NASA had built since shuttle. And I was the chief engineer for that.

And that was when it just sparked. That was when I thought, “Okay, this is what I’m doing for the rest of my career — building big space systems.” And again, the goal was eventually to have people living and working in space. So I did that for quite a while.

Then Voyager called and said, “Hey, we’re building the commercial space station.” And that was the next step. And so I said, “Yeah, I’m in.”

Mike Gruss – Was there a moment where you thought, “Oh, this is feasible. This isn’t just a pipe dream. This is closer than I expected”?

Marshall Smith – Yeah, I think so. You know, right before I left NASA, I spent a good bit of time working on going to the Moon, Mars and beyond. And one of the reasons we were doing that — when I say “we,” NASA — was saying that we were going to step back from LEO and turn that over to commercial space.

Because, you know, the ISS — I’ll just throw a plug in — yesterday was 25 years of permanent crew on ISS. And the ISS wasn’t built by the government. We say it was built by the government, but it was actually built by companies: the companies at Airbus, Lockheed, Boeing, MDA Space, and all the others.

The commercial capability has been out there. It’s been up and running and operating. So the question now is: can companies go build and operate these things on their own and get those private-equity investors? Absolutely. And that’s the first step we’re taking toward actually making an economy in space that is not just funded and propped up by the government.

Mike Gruss – Why do you think it felt so far away, though? Because I think a lot of people will still say commercial space stations feel far away.

Marshall Smith – They do feel that way to some people. I think if you’re involved in the day-to-day, you see the demand and the need.

I’ll just throw out a little plug: for example, we have 55% of our commercial space already reserved, and we’re still years away from launching. And that’s demand right there. So we’re not worried about the market or what’s going to happen.

And of course, as prices come down — for launch, as well as being in space and operating payloads — it’s going to make a big difference. There’s also things like the International Space Station. When you fly a payload on the ISS, many governments are involved, and then there are IP restrictions and things like that.

On a commercial space station, you don’t have to do that. We can make arrangements and deals with companies to release that IP. And that transforms the interest commercial companies have. “Oh, wait a minute, I don’t have to share this cancer drug with so-and-so?” We can come up with other arrangements. And I think you’re going to see a major shift in technology that wants to use microgravity.

Mike Gruss – So let’s back up a minute. You work at Starlab. Tell us about the commercial space station you envision — what it looks like, how it would operate. Go through the basics, the fundamentals.

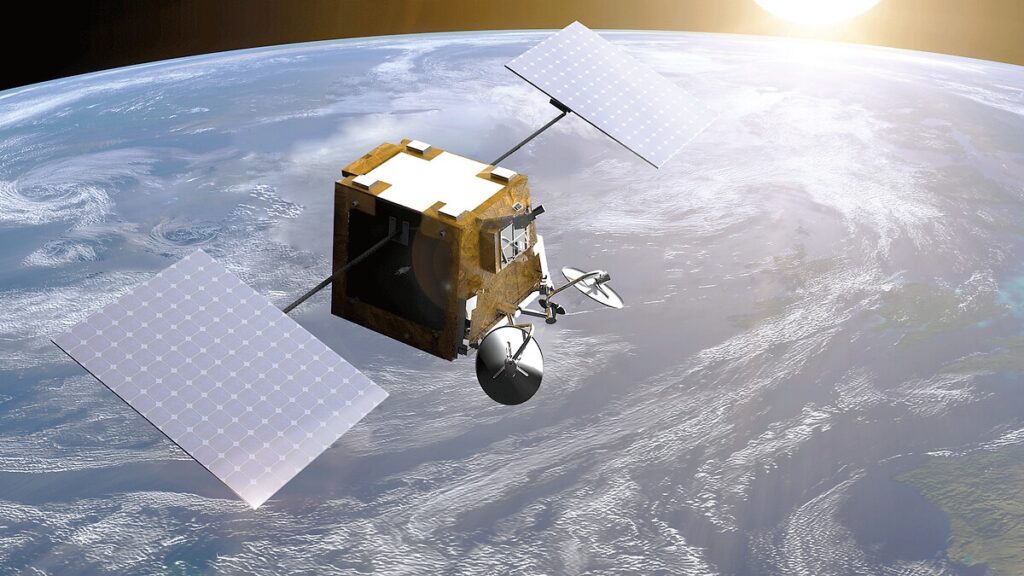

Marshall Smith – Yeah. So there was a picture up there briefly. It’s actually very large — about 40% the pressurized volume of the ISS. You know, the ISS when it was built was sized because that was the biggest module that would fit in the back of the space shuttle. And that’s just the way it was.

We’re not limited to that anymore. We have very large vehicles being developed today. And I have no doubts we’ll be ready when we’re ready to launch. Because we’re just going to orbit — we’re not trying to go to the Moon and land.

So those station volumes are much, much larger. This vehicle is 40% the pressurized volume of the ISS. It has three floors — three levels — very large levels.

We had a full-size mock-up recently, and people walked around saying, “Holy cow, this is huge.” It is a sea change in how we do business.

Payload capability? We have 100% of the research payload capability the ISS has — not counting external payloads, and we have loads of external capability as well. And when I say we’re 55% reserved, we’ve already got 55% of ISS-equivalent research space booked.

Another thing: it’s designed differently. The ISS was designed to get countries to work together, which it has done amazingly. But if you look at the ISS, you see cables and wires everywhere, stuff jammed anywhere. It’s because it wasn’t designed with research in mind.

What we’re doing is designing this first Starlab as a research system, a science system. It’s designed around the payload bays. It’s designed around giving proper video and communication capability, control, and AI systems so payloads can be used, data can be sent down, and hardware can be taken in and out.

And finally, ISS was designed by engineers for engineers — that’s the way I like to say it. It looks like it and feels like it — and actually smells like it.

We’ve partnered with Hilton, for example, and a company called Journey. If you’ve seen the Sphere in Las Vegas, they’re behind that. We’re partnering with people who have experience in hospitality and dealing with people — smells, microgravity, comfort. They’re bringing that expertise to our designs.

Mike Gruss – What does that mean? What does it look like? Because many of us have the experience of seeing astronauts with wires everywhere — clutter. But some of the images you’ve shown with Hilton or Journey look like an office space or a hotel room.

Marshall Smith – Yeah, it’s much cleaner. And one reason we can do that is because, with size, we can put things behind panels. On ISS it’s very difficult to maintain things because you can’t access behind them.

In our case, we can design for that capability. It lets us control the clutter a lot better.

And, for example, the Hilton team — when we talked to them, they said, “Wait a minute, we don’t have to be sleeping on the floor? We can sleep anywhere?” They’re not your traditional space partner. And they are wide open with ideas.

They presented some extremely unique ideas — I can’t go into them because they’re patented or in process — but they help crew sleep. Sleeping in space is really difficult. Some astronauts love it, but many say it’s difficult because your body is used to gravity, blankets, pressure.

Without that pressure, some people struggle. So Hilton came up with ways to make that a much more enjoyable experience. We want it to be pleasurable as well as useful.

Mike Gruss – So it’s now November 2025. You guys are hoping to launch in 2029. What has to happen between now and then?

Marshall Smith – A lot of work. Yeah. So we’ve been designing, developing… When I talk about our team — Starlab is a joint venture. It’s an international joint venture between Voyager, Airbus, Mitsubishi, Palantir, MDA Space, which is Canada — the CanadaArm team.

All of these entities — oh, and we just added SAS, a Belgian company, Space Applications Services, which is doing payloads and other systems.

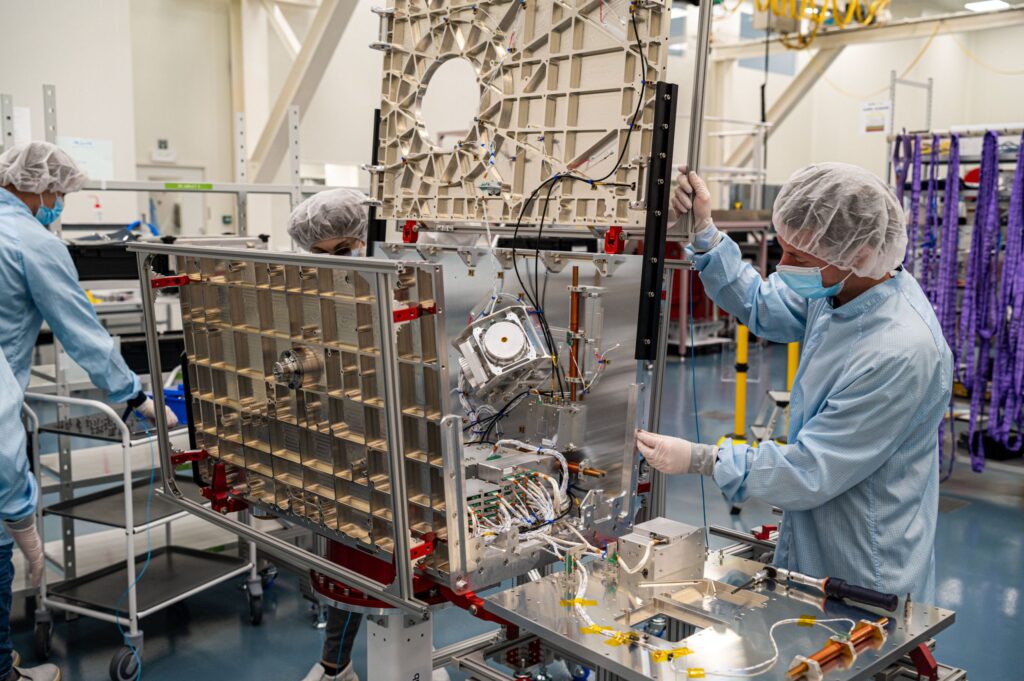

The reason I bring them up is because all of us, including Voyager, have built and operated systems in space. What we need to do now is take those systems, design those systems, and turn them into manufacturing.

We’ve just finished all of our subsystem PDRs. I think we have one more next week — Preliminary Design Reviews. Then we’re going to start our Critical Design Review in December, and then we’ll start that next phase.

But we’re already turning on hardware manufacturing. We’re building structures. We’re doing power systems. All of the hard work — we’ve got to design, integrate, build, test — and then we’ll be ready to go.

So, a lot of work to go. But one of the things we can do is move at the speed of commercial. When I was in the government, it would take me two years to go buy something that cost $50 million because of procurement regulations. I can literally do it in two months in industry. That makes a huge difference.

A lot of people with a traditional mindset think things take a long time because the government is involved. But when they’re not, and when you can move at the speed of commercial, it makes a huge difference. And that has nothing to do with safety. People say going that fast isn’t safe — that’s not true at all. We’re not sacrificing anything in that respect.

Mike Gruss – What do you think the risks are right now to meet that 2029 deadline?

Marshall Smith – The risk to meet that 2029 deadline? Well, always something. Something always comes up. When you’re building something this big — and I’ve done a lot of large space projects — there’s always what I call “controlled chaos.”

You’ve always got to be looking at the unexpected unexpected. You’ve got to spend your time managing the little things.

For example, I was working on a program one time — everything was going great, we had literally thousands of things coming together at once. And we had a problem with the wiring harness used to plug into the flight computers. Somebody didn’t order a part.

Well, what do you do? It could take the entire program down for six months. So you go solve those problems. That’s the process of building flight hardware — constantly managing every single thing. That’s the risk you run.

But from a technology-risk standpoint, I don’t really see big issues. We’ve been building and operating these systems in space. That’s one of the reasons NASA turned over low Earth orbit — so they can go do the harder things: the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

The core technology exists. The harder part is managing people — getting the right teams, keeping them engaged — which is something I really enjoy doing.

Mike Gruss – You mentioned the 25th anniversary of the International Space Station, and there’s debate right now about this idea of a continuous heartbeat in space. What are your thoughts on that? Should there be a continuous heartbeat?

Marshall Smith – Yeah, great question. And that debate has been raging — even today. I have a certain opinion: we’ve spent the last 25 years building an industry and a market around being able to live and work in space.

If we went back to the shuttle days, where we go up for a few weeks and come home, or leave something there and then come home — most experiments still need human interaction. That’s going to continue. I don’t see that changing.

Number two, what would it do to our overall industry? If I’m only going up for 30 days, I don’t need visiting vehicles delivering tons of cargo. People aren’t living there. You just bring it with you.

That would make a huge difference. And then when the time comes to spin back up after a gap — that’s a lot harder. Companies aren’t in business to wait around for years. They need to keep production lines going.

So I think a gap would be very hard on the market.

And then we look at other stations that are out there — they have full-time development capability. Some of it is actually hypersonic missile material. Those are things you can’t do on the ground — and not something I’d want to relinquish because we feel like there might need to be a gap.

I don’t think there needs to be a gap. We let companies decide what they want to build based on commercial markets. Most of the money is privately funded anyway — not like commercial crew or commercial cargo. In CLD it’s more like 70/30, maybe 60/40.

So when private markets are funding this, you need the business model to stay intact.

Mike Gruss – Is there a prestige factor to simply saying, “We’ve discontinued”?

Marshall Smith – I think that’s possibly true. But to me, it’s not really about just that.

I think continuous presence is necessary — a business decision, a national security decision, a global leadership decision.

If we’re not there, then where are people going to go? They’ll go somewhere else. And I don’t think that’s what we want.

Mike Gruss – Can you talk a little bit about the market for commercial space stations? Because that’s something that’s hard to grasp.

Marshall Smith – Well, this first Starlab we’re building is designed around science and research — because that’s the market we have now. Mostly government and private-industry funded.

I think you’ll see it start that way, but there’s going to be quite a bit of private interest. We’re already 55% commercially reserved.

The market is really in the things that have been tested and we know work in space — for example, biopharma, cancer drugs. Space manufacturing — manufacturing in microgravity.

It sounds kind of science fiction, but 10 years from now you might be getting your kidney printed in space. In 15–20 years.

Those are real things being talked about.

So Starlab 1 is science and research. Starlab 2 could be manufacturing. And the cost is going to come down dramatically from Starlab 1 to 2 to 3 to 4.

A country could have its own Starlab.

Mike Gruss – You talked about the investment piece. You’ve been on both sides — NASA and industry. How do federal investment, university research, and private development each play a role? And have your views changed?

Marshall Smith – Interesting point. In government, you’re not trained to understand private markets. You worry about how much money Congress gives you.

Coming into private industry and seeing the market — investors are interested in one thing: making money. That’s what we all do in the stock market.

When investors see commitment from the government, they’re all in. I see this all the time.

When it comes to universities and private institutions — they’re all in as well, because it accelerates what they get paid to do: research. Using a facility like Starlab accelerates that.

We’ve partnered with Ohio State, for example. We have a science park — Vista — taking the Earth model into space to accelerate research.

Between all three — government, academia, private — getting them all engaged is a big part of our model.

Mike Gruss – It’s difficult to keep that ecosystem working the way all three legs of that stool would want it to work.

Marshall Smith – It is a juggling act sometimes. But everybody’s motivated.

The difficulty comes when someone says, “We’re going to do this instead of that.” Then the markets get perturbed.

Mike Gruss – Let’s talk about one other news item here, which is the—you talked about the CLD program, Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations program. There have been some changes there, getting away from fixed-price contracts, using agreements to help develop these space stations. What’s your view on how NASA can best help further development of this area?

Marshall Smith – Yeah, I’ve been very clear with NASA and with people I used to work with about things.

Mike Gruss – What have you said?

Marshall Smith – What I’ve said is: industry needs commitment. The longer you don’t commit to a path, the less investment you’ll get.

I’ve heard this — and I’m going to say it for you guys — I’ve heard people say, “Well, we don’t have enough money.” There’s this mindset in government: the only money they have is what they can give you.

And I’m like, “Wait a minute. You’re not supposed to have enough money. That’s not the point. The point is: you commit to a path. We’ll go raise the money. Don’t worry about that. We’ve got that.”

And I think that’s the key. So any approach — I want to make sure the government gives commitment very quickly. That will help kick this off.

And number two: don’t be prescriptive about how we go do the job. For example, in our case, we’re using very robust, well-known, well-understood, high-TRL technology — Technology Readiness Level — which basically means it’s been flown before. We’re using a system that’s very well known.

Don’t tell me I have to do a particular type of mission, because that might not fit our business model. And the business model has to be built around what public and private partners and investors want to see.

Sure — we’ll go make sure it works before you fly on it. That’s fine. But let us develop that path.

Those are the two things I’ve told the government.

Mike Gruss – We’ve got about two minutes left here. Let’s say it’s 2030 — we’re coming back for another version of the Discovery Series. What do you hope has happened? What changes do you think have happened? What kind of successes do you hope to have had, and what else do you see changing within the space industry between now and then?

Marshall Smith – Yeah… two minutes. I have a lot to say.

So the short story is: we’re going to be in operation. We’re going to be on orbit. We’re going to be fully subscribed. We’re going to be developing cancer drugs. We’re going to be developing, you know, the basis for kidneys and retinal implants and those types of things.

To me, it’s like the iPhone. When iPhones came out, people looked at them and said, “What do I do with this?” And now you can’t live without it.

I see that happening. We are now going to unleash commercial space to go do things that I actually can’t even imagine today. I really can’t. I can think about the things we know about — but there are things none of us have insight into yet.

AI is going to make a big impact as well.

Mike Gruss – Hit me — say something specific about AI, because we were talking about that.

Marshall Smith – Well, for example, we’re going to use AI in operation systems and development. We’re using it today in design and development of our systems. We’ll use it in operations.

We can take what used to require 200 people and get it done in a week. Literally — we’re doing that right now.

And for example, if we’re operating the system — in the past, if you had to make a change to your logistics systems, it would take you weeks to redo everything. We can do it literally in an hour. Those types of things.

And we do it with one person — not 100 or 50. Huge, huge impacts there.

But honestly, in 2030, what I want to see is this market taking off — because we’re going to start seeing the inputs. And we’ll be building Starlab 2 and Starlab 3.

Mike Gruss – Great. Marshall, thanks so much. This was a lot of fun. I appreciate you coming.

Marshall Smith – Thank you.

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly