Now Reading: Voyager Technologies acquires Estes Energetics

-

01

Voyager Technologies acquires Estes Energetics

Voyager Technologies acquires Estes Energetics

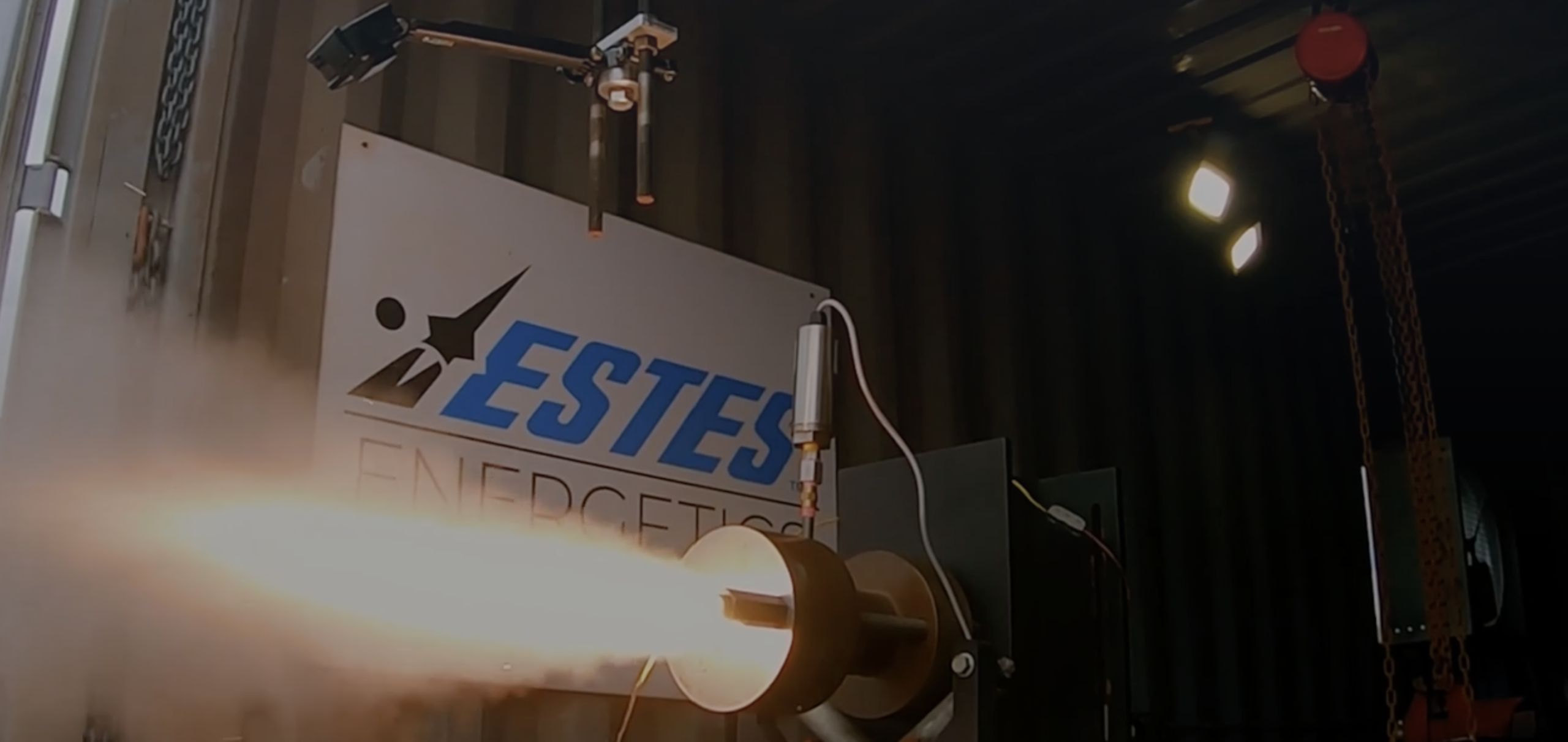

WASHINGTON — Voyager Technologies announced Nov. 20 it acquired Estes Energetics, a supplier of solid rocket motors and energetic materials. The move underscores Washington’s push to rebuild domestic production lines for critical defense components.

The Denver company, which recently went public, is a space and defense technology firm whose growth strategy now leans heavily toward national security programs. For Voyager, this latest acquisition secures long term access to U.S. sourced energetics. Estes is the country’s only producer of military grade black powder, a key ingredient used as an igniter in solid propellant systems.

Voyager did not disclose terms of the deal.

“This significantly strengthens the position of our propulsion capabilities,” said Dylan Taylor, chairman and CEO of Voyager. “As global supply chains become increasingly fragile, these capabilities must be built, qualified and safeguarded here at home.”

The acquisition continues Voyager’s buying streak across propulsion, sensors and space infrastructure. The company snapped up ElectroMagnetic Systems in August, adding artificial intelligence and machine learning tools for space based radar, and acquired electric propulsion supplier ExoTerra Resources in October. Voyager says the combined portfolio is meant to support bids for major programs, including the Pentagon’s Golden Dome missile defense effort.

Small company with outsized strategic value

Founded in 2021 as a spin out from model rocket maker Estes Industries, Estes Energetics operates in a niche but strategic corner of the defense market. Through its Goex Industries subsidiary, it manufactures black powder and related compounds that are essential for rockets, missile defense systems and tactical munitions. Estes runs facilities in Colorado and Louisiana.

Matt Magaña, Voyager’s president of space, defense and national security, said Estes will support the company’s ability to “scale munitions production quickly and predictably for growing market demand.”

The Pentagon has been urging industry to expand energetic materials manufacturing capacity and reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. Key inputs such as nitrates, perchlorates and other energetic chemicals have long been tied to overseas production, creating bottlenecks across missile and interceptor programs.

Karl Kulling, CEO of Estes Energetics, said joining a larger parent will position the company to “expand production, invest in new capabilities and support customers across defense, space and national security.”

Control of black powder production gives the company leverage in an area where the U.S. has few domestic options and where demand is rising as the Pentagon accelerates missile and munitions orders.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

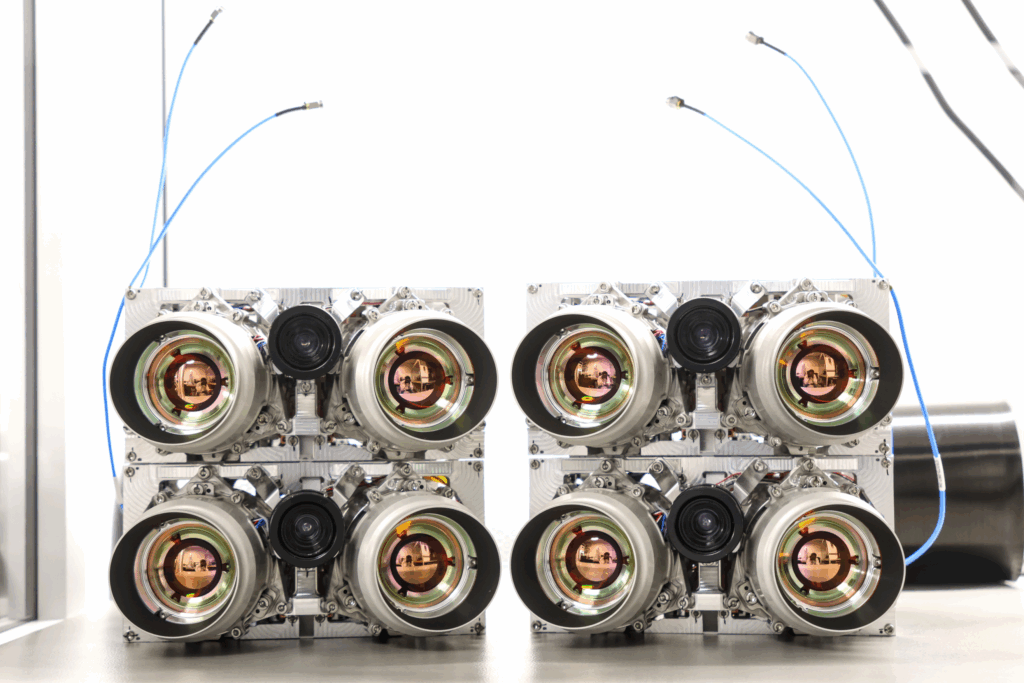

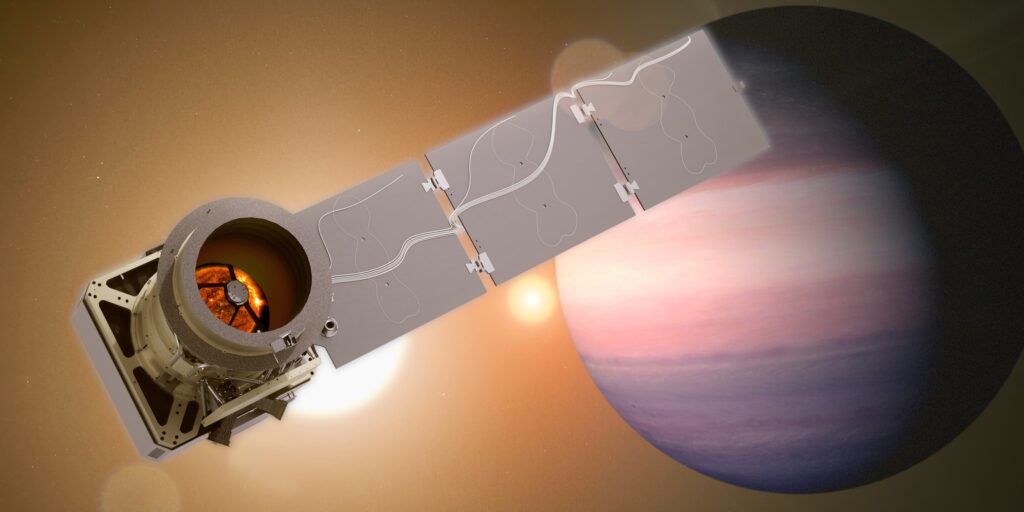

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly