Now Reading: Space Force awards first prototype deals for space-based interceptors under Golden Dome

-

01

Space Force awards first prototype deals for space-based interceptors under Golden Dome

Space Force awards first prototype deals for space-based interceptors under Golden Dome

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Space Force has begun awarding prototype contracts for space-based interceptors, an early step in the Pentagon’s push to field its planned Golden Dome missile defense architecture.

A spokesperson confirmed Nov. 25 that the Space Systems Command issued multiple awards for space-based interceptor (SBI) prototype demonstrations through competitive Other Transaction Agreements, a contracting mechanism designed to speed work on emerging technologies.

“The selection process was robust and thorough. The Space Force will lead a fast-paced effort in partnership with industry to develop, demonstrate and deliver prototype interceptors,” a Space Force spokesperson said in a statement to SpaceNews.

The names of the contractors are being withheld “as they are protected by enhanced security measures.” Contract values were also not released. Because the awards are OTAs, they fall outside the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation and do not require public disclosure.

OTAs allow prototyping

Other Transaction Agreements give the Defense Department more flexibility on requirements, cost, data rights and schedules. They are commonly used for rapid prototyping programs and help draw in companies that may not normally work with the Pentagon because of the regulatory overhead of traditional procurement.

The SBI awards follow a September solicitation seeking prototypes for boost-phase interceptors, which are meant to target missiles in the first minutes after launch.

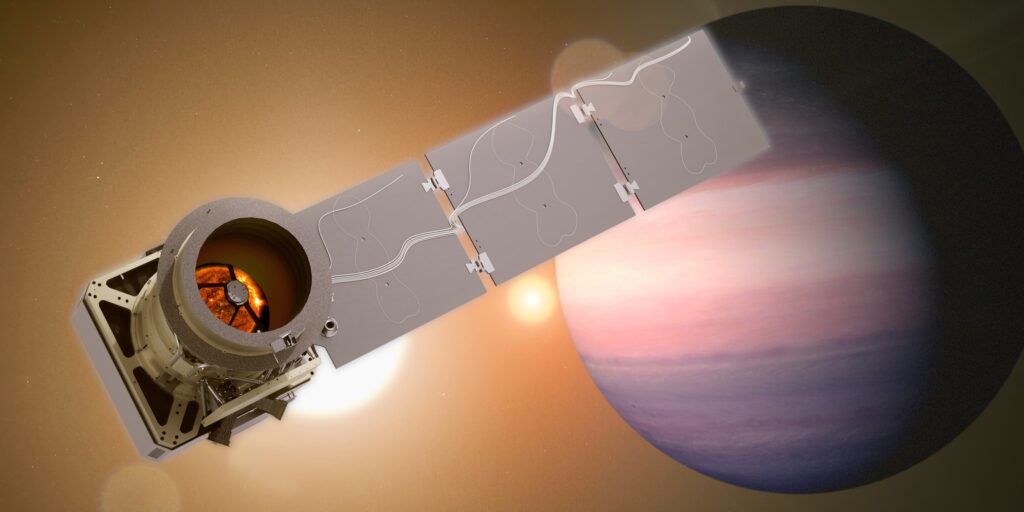

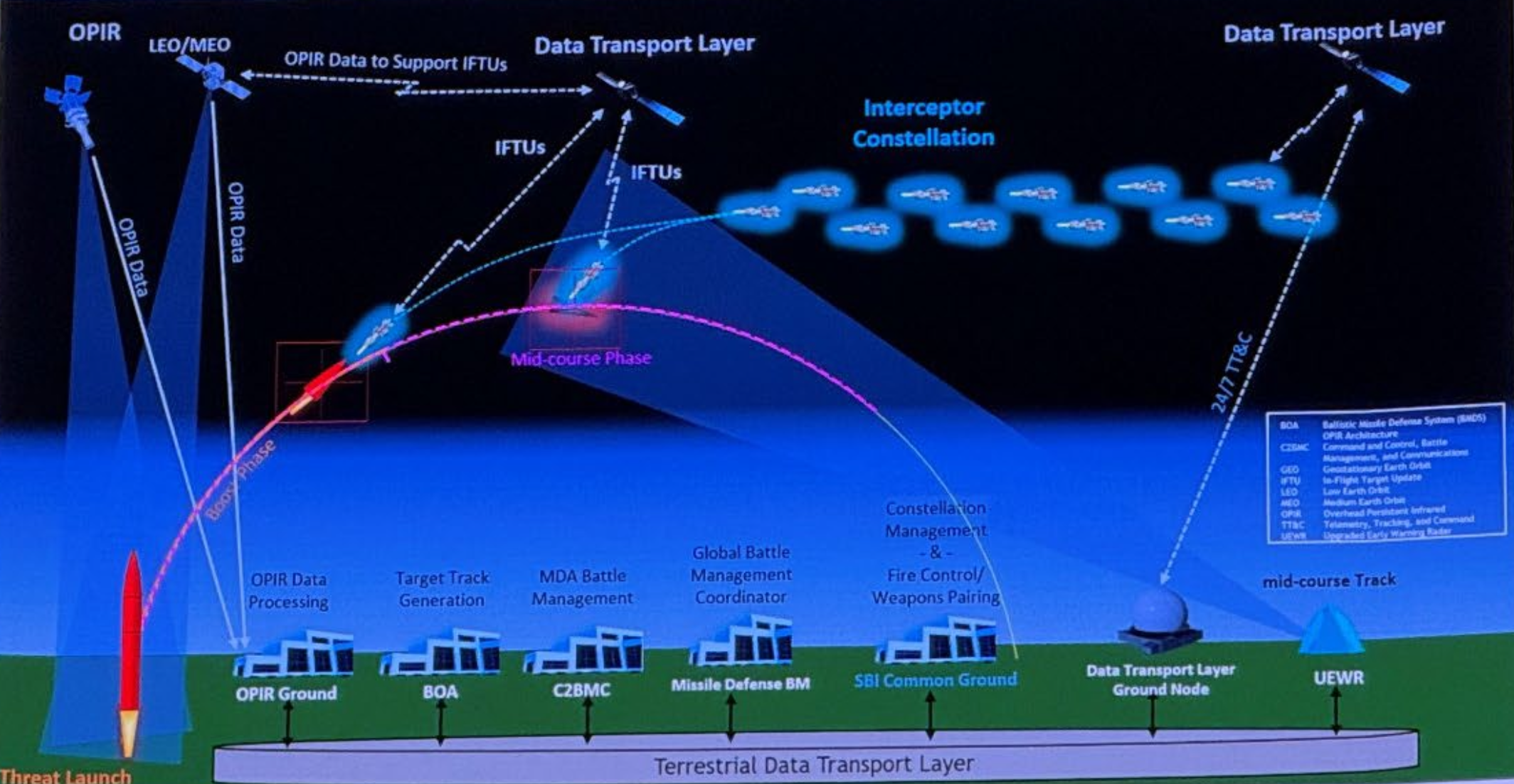

Golden Dome is run by Space Force Gen. Michael Guetlein, who reports directly to Deputy Defense Secretary Steve Feinberg. It is envisioned as a multi-layer homeland defense system combining new sensor networks, command and control tools, and a mix of ground and space-based kinetic interceptors. Space-based interceptors would maneuver in orbit and strike hostile missiles during flight.

How the interceptors are used depends on the final architecture the Pentagon selects.

Boost-phase defense aims to hit a rocket while it is still burning, bright, and comparatively easy to track. But reacting within seconds requires a large number of satellites spread across low-Earth orbit.

Midcourse defense engages the warhead later in space, giving operators more time, and reducing the number of required satellites. It also demands far more advanced sensors to distinguish real warheads from decoys.

In a separate announcement last week, SSC issued a pre-solicitation notice for kinetic midcourse interceptor concepts. The command expects to release a Request for Prototype Proposals around Dec. 7, with awards planned for February 2026. These awards will also be fixed-price OTAs and may include prize competitions.

Feasibility questions

The boost-phase SBI approach has drawn scrutiny from analysts who argue that the physics and constellation size requirements make the concept difficult to field at scale.

Todd Harrison, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said during a recent SpaceNews event that the intercept window for a boost-phase shot could be as short as 30 seconds. He pointed to what he calls the “absenteeism problem” as satellites in low-Earth orbit spend most of their time out of position relative to any given launch site.

According to his calculations, intercepting even one missile reliably might require about 950 orbiting interceptors. If an adversary fires 10 missiles, the constellation might need to grow to 9,500 interceptors. The scaling cost, he said, could make the architecture impractical.

Experts have said that the size, cost and technical demands of space-based interceptors mean the Pentagon will need to narrow its architectural choices before committing to a full constellation.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly