Now Reading: Did we just see dark matter? Scientists express skepticism

-

01

Did we just see dark matter? Scientists express skepticism

Did we just see dark matter? Scientists express skepticism

Directly detecting dark matter is one of modern science’s holy grails. Despite making up 85% of all matter in the universe, this elusive substance – first theorized to exist in the early 1930s – doesn’t interact with light, rendering it invisible. But now, a bold new study claims to have recorded direct evidence of dark matter for the first time.

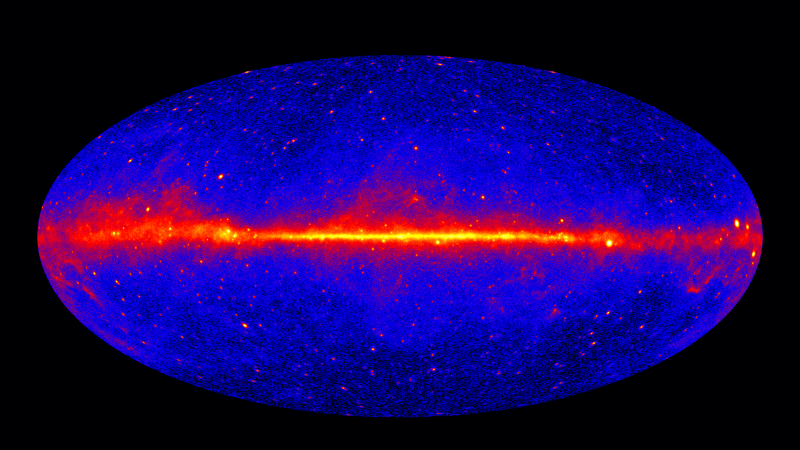

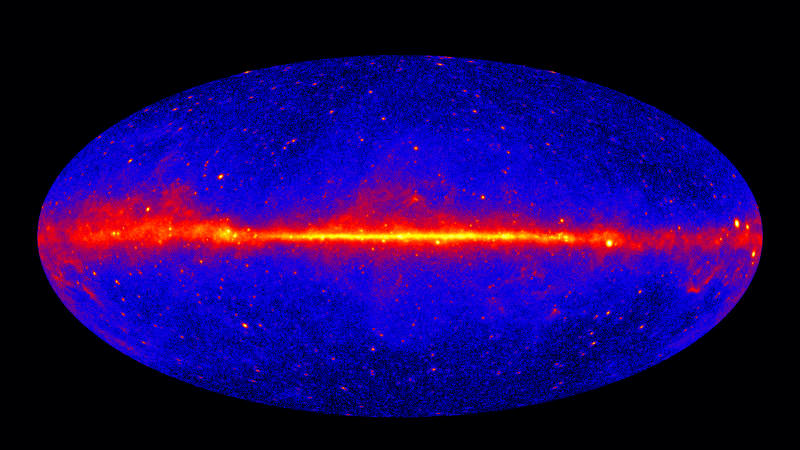

The single-author paper, which the University of Tokyo announced on November 26, 2025, is a new analysis of data captured over 15 years by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which detects high-energy gamma radiation.

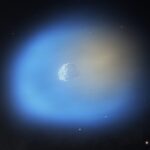

The research identifies a ‘halo’ of gamma ray emissions spreading out from the center of our galaxy. And it claims this matches the emissions we would expect from collisions between dark matter particles.

If accurate, it’s a momentous discovery. As study author Tomonori Totani said:

If this is correct, to the extent of my knowledge, it would mark the first time humanity has ‘seen’ dark matter.

But amid excitement across the media, scientists on social media and elsewhere are expressing skepticism. This is far from a new claim, many have pointed out. And numerous studies of the same data have failed to find evidence for this highly desirable conclusion.

Totani published the peer-reviewed paper on November 25, 2025 in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

The big claim

The study centers on a dark matter candidate – just one possible answer to what dark matter might actually be – known as the WIMP, or weakly interacting massive particle. The important thing about WIMPs is that, when they collide, they should annihilate each other and release a burst of gamma radiation.

So for decades, scientists have been looking toward the center of our Milky Way galaxy – where dark matter should be concentrated – to find an unexplained excess of gamma rays.

And that’s exactly what this new study claims to have found. Using data from the Fermi Space Telescope, Totani performed a new analysis of the regions around our galaxy’s core, and found what appears to be a new gamma ray signal. He said:

We detected gamma rays with a photon energy of 20 gigaelectronvolts (or 20 billion electronvolts, an extremely large amount of energy) extending in a halo-like structure toward the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The gamma ray emission component closely matches the shape expected from the dark matter halo.

In other words, Totani reports a peak in gamma rays at about the energy level predicted for dark matter collisions. And this signal seems to get weaker as it gets farther from the center of the galaxy, matching the expected distribution of dark matter into an enormous halo structure around the Milky Way’s core.

Importantly, he argued that this signature isn’t easily explained by any of the many astrophysical phenomena that release gamma rays, such as pulsars or supernova remnants.

And, while noting that further independent analysis would be needed to confirm the finding, the University of Tokyo press release stated that Totani is:

… confident that his gamma-ray measurements are detecting dark matter particles.

Dark matter, or light on evidence?

But for the astronomers we spoke to, or whose words we read via social media, this confidence appears misplaced. We spoke to Case Western Reserve University astrophysicist Stacy McGaugh, an expert in galaxy dynamics and dark matter, who noted that we’ve been here before.

That is, the Fermi data used in the study has already been extensively studied, and a similar excess of gamma rays was identified as early as 2009. Over the past 16 years, numerous studies have failed to find strong evidence that this signal connects to dark matter. As McGaugh succinctly put it:

It turned out to be wrong then, [and] I expect it is wrong now.

He went on to explain that any confidence in this sort of detection is limited by just how chaotic our galaxy is, particularly toward its core. The signal could have come from a handful of other known gamma ray sources, and potentially some unknown ones. McGaugh said:

The galactic center is a messy place with lots of astrophysics. Sorting out a legitimate dark matter signal means correctly accounting for all that is not dark matter, which is most of it.

It would be more persuasive if they saw the same signal in dwarf galaxies, which are less messy. They should, but they don’t. That says to me that the signal is likely astrophysical in origin [coming from objects made of normal matter], not dark matter.

Study skepticism

With so many gamma ray sources to account for in our galaxy, conclusions drawn from the Fermi data can be vastly different depending on the method of analysis. As Stockholm University astrophysicist Jan Conrad told BBC Science Focus:

It is notoriously difficult to make these claims with Fermi data.

And for McGaugh, the methodology in this case doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. One issue surrounds a key parameter in the analysis: the density of dark matter in our galaxy. McGaugh explained that the study used data from a simulation to account for dark matter distribution, despite the fact that real measurements exist.

The author appears to assume a dark matter distribution from a simulation rather than a measurement. This is something many people (including myself) have constrained in various ways. The real-universe density of dark matter is much less than the simulations say it should be. That predicts a much weaker signal.

With such noisy data, decisions like these can be the difference between detecting dark matter and ruling it out. And this case, McGaugh said:

A favorable assumption has been made in the analysis that makes a detection plausible.

Of course, there’s a chance we’ll look back on Totani’s study as a genuine dark matter detection. And, in that case, it would be a remarkable discovery. But currently, though gamma ray emissions remain a promising path toward detecting dark matter, the verdict on this study isn’t in. For now, other scientists have stepped up to say that more work needs to be done before we can claim to have detected dark matter.

Bottom line: A bold new study claims to have made the 1st ever direct detection of dark matter. But at least some scientists – perhaps many scientists – remain unconvinced.

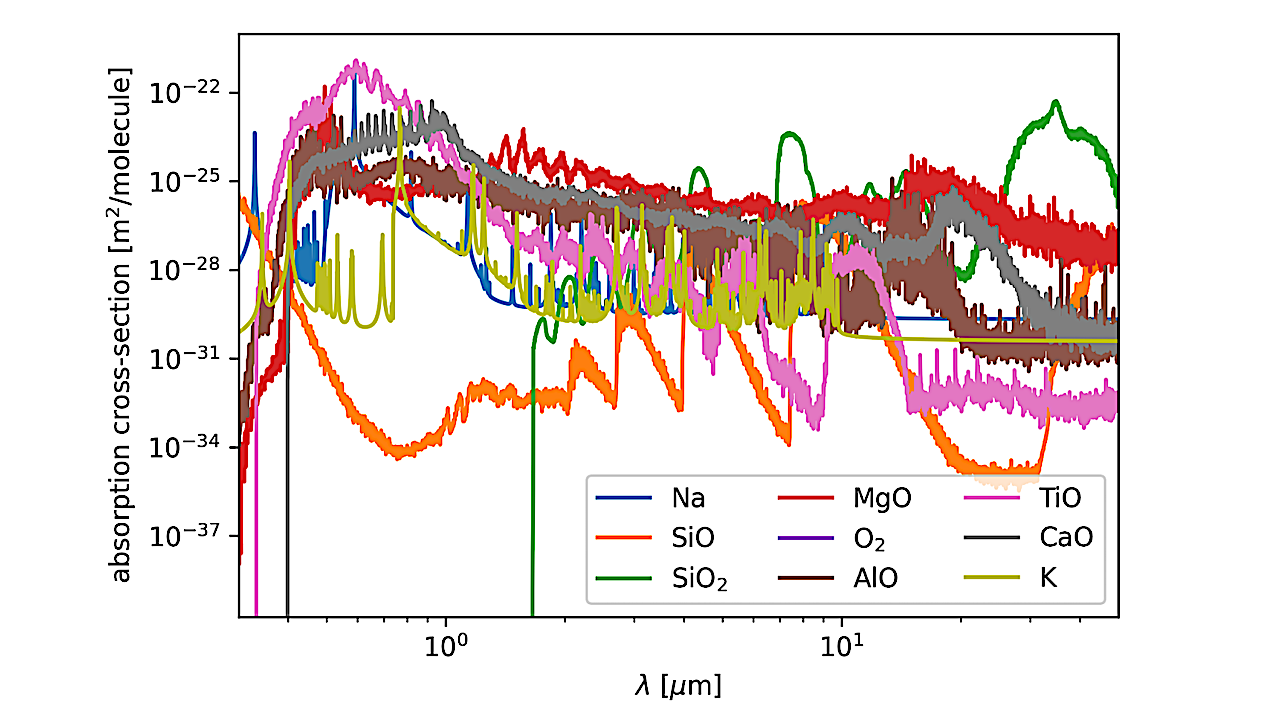

Read more: Dark matter might leave a colorful ‘fingerprint’ on light

The post Did we just see dark matter? Scientists express skepticism first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly