Now Reading: The overlooked space race: keeping satellites alive

-

01

The overlooked space race: keeping satellites alive

The overlooked space race: keeping satellites alive

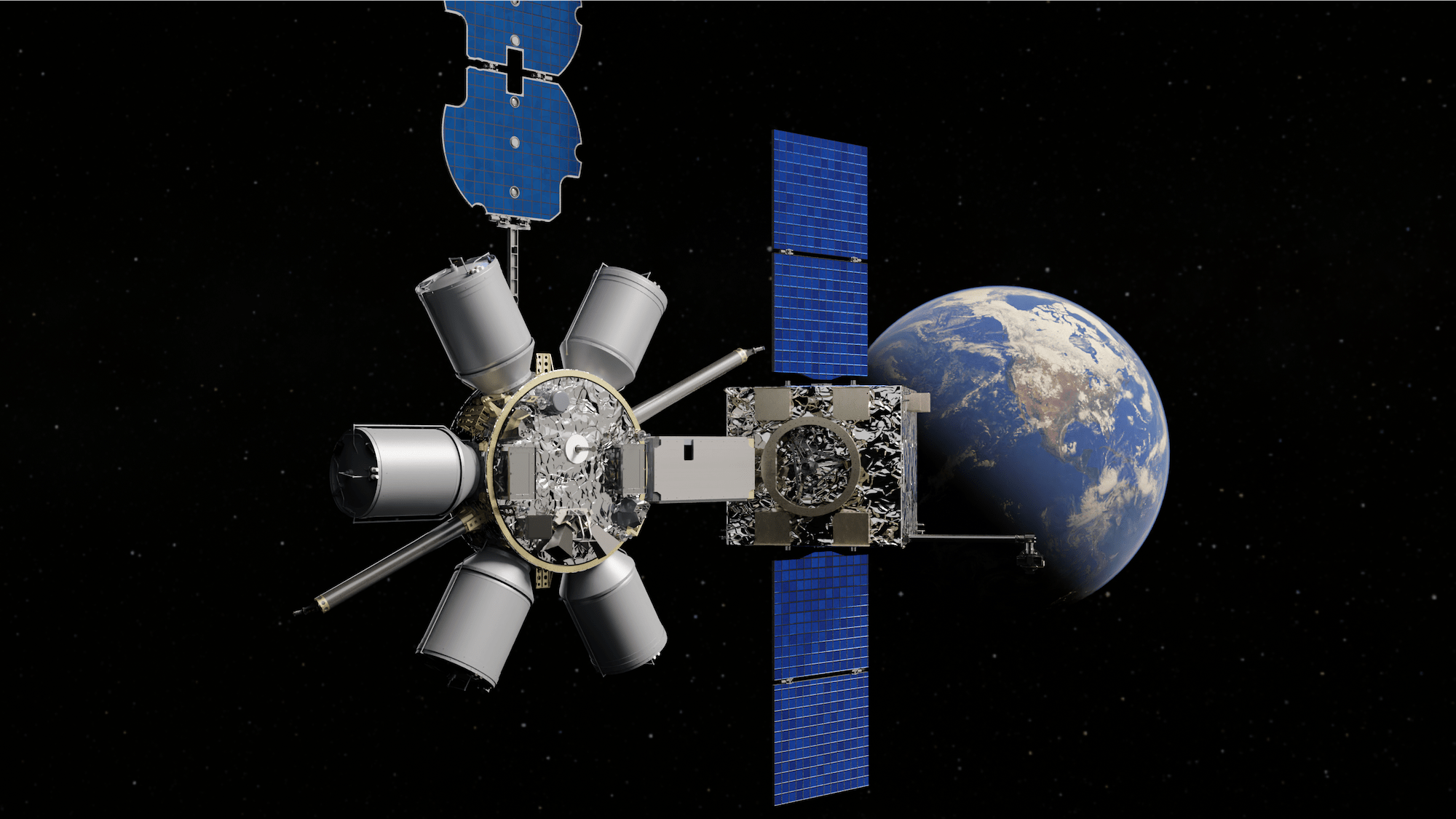

China’s lunar ambitions grab attention, but a quieter milestone that the country achieved earlier this year could have longer-term implications for how nations operate in orbit. In mid-2025, China pulled off what American officials had talked about for almost two decades but never operationalized: a satellite-to-satellite refueling in geostationary orbit.

The Shijian-25 spacecraft docked with its older sibling, Shijian-21, and topped off its tank. On paper, it was a life-extension operation. In practice, it was a signal. China can now keep key spacecraft alive and maneuverable in an orbit where even small shifts are strategically valuable.

The United States has led this field. DARPA’s Orbital Express mission in 2007 proved that satellites could refuel and service one another. But with no pressing threat and satellites primarily designed to sit in place for decades, the military shelved refueling as a science project. Space assets were launched, used and retired without so much as a tune-up.

That status quo is cracking. U.S. Space Command’s push for “dynamic space operations” — the ability to maneuver in orbit without worrying about running dry — demands logistics the military has never had. Satellites used for surveillance and threat tracking, especially in geosynchronous orbit, face adversaries that can shadow, approach or disable them. Mobility is defense, military leaders point out, and mobility requires fuel.

Industry officials see the opening. Northrop Grumman’s SpaceLogistics unit has already adapted pieces of DARPA’s technology into commercial life-extension vehicles. Joe Anderson, a vice president at the company, summed up a frustration widely shared in the sector: Every other warfighting domain invests heavily in maintenance. Space, the most unforgiving domain of all, invests almost nothing.

“Space has been the one domain where all our money is spent on the asset, and there’s been essentially zero money spent on support and maintenance,” he told an industry audience recently.

The Space Force is trying to change that but is moving deliberately — some say too deliberately. Technology demonstrations are on the books for 2026 and 2027. Trade studies are underway. Officials want to know whether the investment is worth it.

Meanwhile, Beijing is proving out capabilities that make satellites not just longer-lived, but more capable in a crisis.

A report published Nov. 6 by the Mitchell Institute argues that logistics will determine whether the U.S. can operate effectively in orbit during a prolonged confrontation.

Refueling is only part of the picture. Servicing, assembly, manufacturing — essentially the ability to repair, reconfigure or upgrade spacecraft — could turn platforms that now perform one job for 15 years into assets that evolve over time.

Charles Galbreath, a retired Space Force colonel and the report’s author, said early signs are promising. The Space Force’s decision to make its next-generation “RG-XX’’ satellites refuelable marks a shift. Those spacecraft will replace today’s GSSAP surveillance satellites, which are critical for monitoring activity in geosynchronous orbit but are limited by the fuel they carry at launch. Once they run low, maneuvering becomes a luxury.

But Galbreath also warned that experiments and design tweaks aren’t enough. “We need to take the next step and actually produce that at scale,” he said. One-off prototypes won’t deter a competitor that builds operational systems.

John Shaw, a retired Space Force lieutenant general who long pushed for maneuverable spacecraft supported by in-orbit logistics, put it even more bluntly. “We demonstrated refueling with Orbital Express well over 15 years ago,” he said. “Now, the Chinese have clearly shown they can do it.”

The technology is here, he said. Commercial firms are ready to build. What’s missing is a commitment to fielding an operational architecture — a recognition that the U.S. can no longer treat satellites as disposable. If spacecraft can be refueled, repaired and upgraded, Shaw contends, the U.S. gains the freedom to maneuver in a part of space where position equals power.

China seems to understand this. The push for deep-space exploration depends on strong logistics, as Shaw pointed out. Sustained lunar operations will require the same support and resupply backbone now being debated in orbit.

Getting to the moon, and staying there, ultimately hinges on the same logistics challenges the military is confronting closer to Earth.

This article first appeared in the December 2025 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

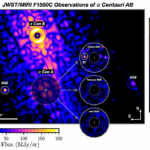

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits