Now Reading: Mercury is hard to spot, but you can catch it in the morning sky this month

-

01

Mercury is hard to spot, but you can catch it in the morning sky this month

Mercury is hard to spot, but you can catch it in the morning sky this month

If there ever was a planet that has gotten a bad rap for its inability to be readily observed it would have to be Mercury, known in some circles as the “elusive planet.”

Mercury is called an “inferior planet” because its orbit is nearer to the sun than the Earth’s. Therefore, it always appears from our vantage point to be in the same general direction as the sun. So near to the sun that it is often difficult to see with the unaided eye. In fact, Copernicus complained that he had never been able to enjoy a view of it, and this was doubtless because he lived at Frombork in northern Poland, near the Vistula River, where the sky near the horizon is often hazy owing to local mists and fog.

Rise to prominence

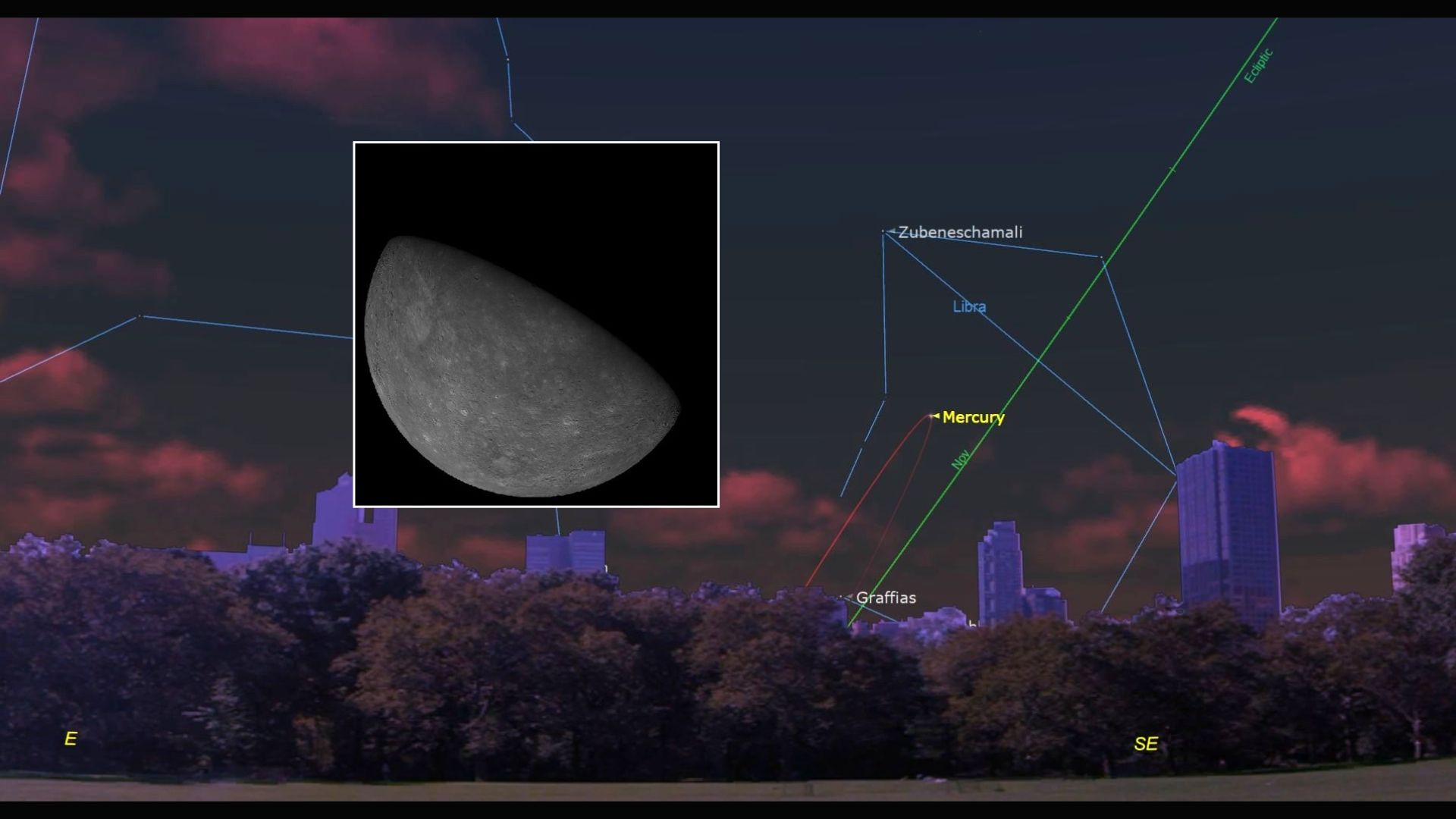

On Nov. 20, Mercury was at inferior conjunction with the sun, passing roughly between the sun and our Earth. Four days later on Nov. 24, Mercury passed just one degree north of brilliant Venus, but the pair were only 10 degrees from the sun and rising about 50 minutes before sunrise, shining at a magnitude of +2.4. Mercury was still impossible to see through the brightness of dawn.

But only three days later on Thanksgiving Day (Nov. 27), Mercury was rising 75 minutes before the sun and increased by a factor of 3.6 times in brightness to magnitude +1.0. It was then fairly easy to locate, close to the east-southeast horizon about an hour before sunrise.

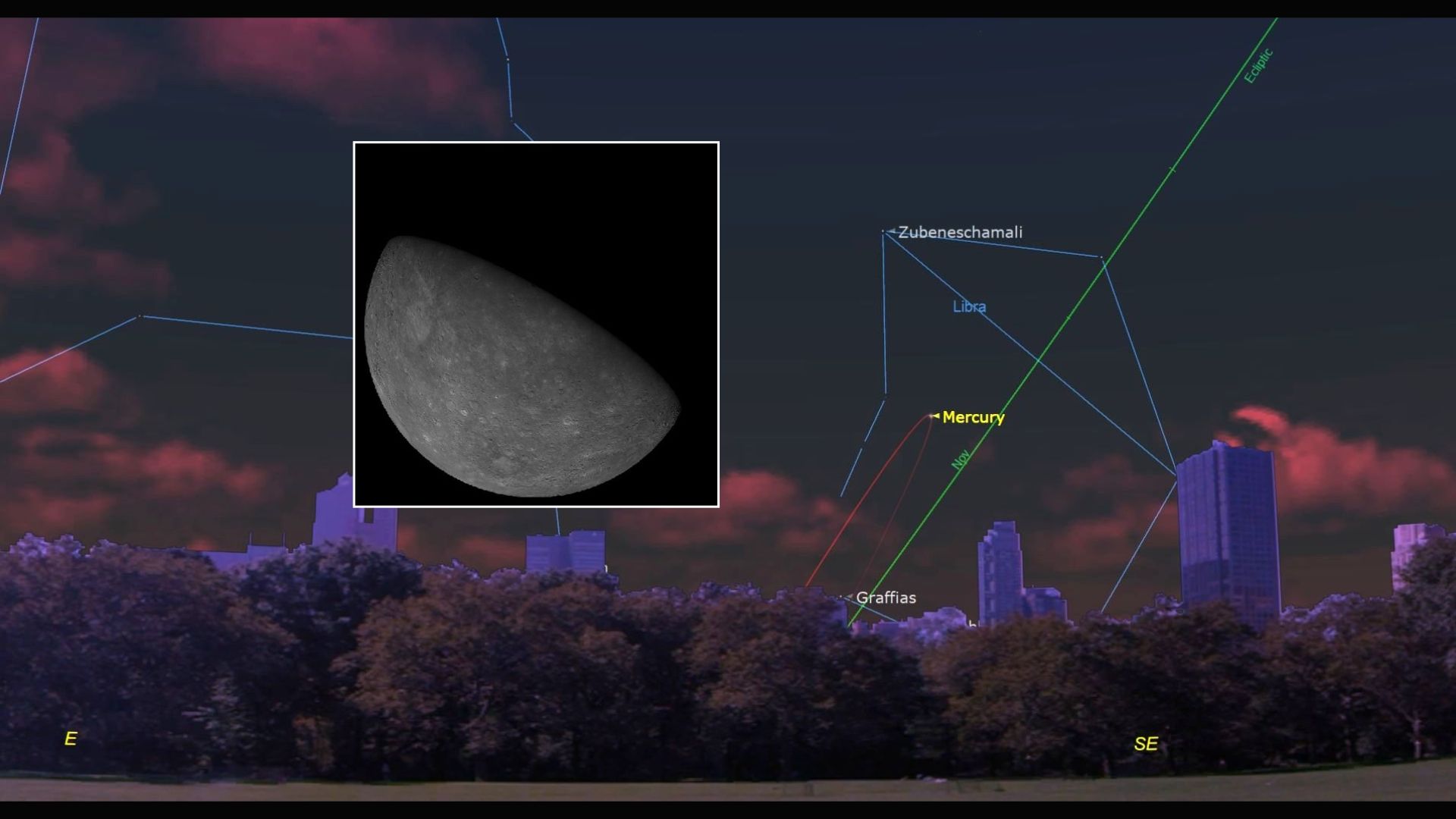

Mercury’s visibility continued to improve rapidly and by Friday morning, Dec. 5 it will rise shortly before morning twilight begins — in a dark sky — and will have brightened markedly to magnitude -0.3. Now all you have to do is just look low above the east-southeast horizon from 40 to 80 minutes before sunrise for a bright yellowish-orange “star.”

An unusually favorable greatest elongation occurs on Sunday, Dec. 7, even though Mercury is only 21 degrees from the sun. At magnitude -0.4 (among the stars only Sirius and Canopus are brighter), it rises in a dark pre-twilight sky about one hour and 50 minutes before the sun. In the 2025 Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Alister Ling stresses that this will be the “best morning apparition of 2025 for Northern Hemisphere observers.”

Mercury, like Venus, appears to go through phases like the moon. On Thanksgiving Day, Mercury was a slender crescent, 20 percent illuminated by the sun. By Dec. 7, it will appear 62 percent illuminated and the amount of its surface illuminated by the sun will continue to increase in the days to come. So, although it will begin to turn back toward the sun’s vicinity after Dec. 7, it will brighten a bit more to magnitude -0.5 by Dec. 9, which should help keep it in easy view over the next couple of weeks.

Mercury passes 5.5 degrees to the upper left of 1st-magnitude Antares on Dec. 19 but that ruddy star will only shine about one-quarter as bright as Mercury, so you’ll probably need binoculars to spot it. Mercury itself will become difficult to see in bright twilight by around Christmas.

The circumstances that make it happen

There are four reasons why Mercury will be so favorably placed for viewing in the morning sky this month:

- At sunrise in autumn, the ecliptic — the apparent path the sun, moon and planets take across the sky over the course of a year — makes a steeper-than-average angle with the horizon for Northern Hemisphere observers.

- Since Mercury passed the ascending node of its orbit on November 18th, it is north of the ecliptic through much of December.

- In addition, its orbital speed is near maximum, since perihelion (its closest point in its orbit to the sun) occurred on Nov. 23.

- Around the time of inferior conjunction, Mercury is much closer to the Earth, and its angular motion relative to the sun is much greater than around superior conjunction (when it’s on the far side of the sun as seen from Earth).

Exceedingly hot … frigidly cold

In old Roman legends, Mercury was the swift-footed messenger of the gods. The planet is well named for it is the closest planet to the sun and the swiftest of the sun’s family, averaging about 30 miles per second; making its yearly journey in only 88 Earth days. Interestingly, the time it takes Mercury to rotate once on its axis is 58.7 days, so that all parts of its surface experiences periods of intense heat and extreme cold. Although its mean distance from the sun is only 36 million miles, Mercury experiences by far the greatest range of temperatures: 790º F (420° C) on its day side; -270º F (-170° C) on its night side.

Planet with a double identity

In the pre-Christian era, this planet actually had two names, as it was not realized it could alternately appear on one side of the Sun and then the other. Mercury was called Mercury (Latin Mercurius) when in the evening sky, but was known as Apollo when it appeared in the morning. It is said that Pythagoras, about the fifth century B.C., pointed out that they were one and the same.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly