Now Reading: How Spain and Poland pushed Europe’s new priorities with record contributions

-

01

How Spain and Poland pushed Europe’s new priorities with record contributions

How Spain and Poland pushed Europe’s new priorities with record contributions

MILAN – When the European Space Agency announced its new three-year spending plan last month, two countries stood out for the increased size of their contributions.

Poland boosted its budget from 198 million euros ($230 million) in 2022 to 735 million euros in 2025 (a 276% increase). Spain raised its contribution from 933 million euros to 1.871 billion euros (a 101% increase). The jumps came at a time when ESA’s overall budget rose about 30%.

Spain’s new budget has elevated the country to ESA’s fourth-largest contributor, surpassing the UK (1.725 billion euros), which moves to fifth place and is also the only member state to have decreased its budget since the 2022 Ministerial.

Spain made clear that its priority is supporting its industrial base. “Spain will continue to work with ESA to develop its own industry,” said Diana Morant, Spain’s Minister of Science, Innovation and Universities. “The agency should be the architect of the European spatial infrastructure with industry policy that takes into account all of the stakeholders, particularly SMEs, startups and medium-sized businesses.”

Poland, meanwhile, is now ESA’s eighth-largest contributor — after Belgium and Switzerland — rising from 12th place in 2022. Unlike Spain, Poland’s priorities are shaped directly by the geopolitical situation unfolding in Ukraine. As Andrzej Domański, Poland’s Minister of Finance and Economy, noted in his opening speech in Bremen: “Poland believes that Europe’s space policy must prioritize resilience, security, and strategic autonomy. Strengthening the protection of our orbital infrastructure is equally vital.”

But understanding how these national interests translated into the success of ESA’s budget request — and which programs embody each country’s priorities, and how these rising players may influence broader trends in European space spending — requires examining how Spain and Poland played their cards, each driven by different motivations toward a shared objective.

New programs for new necessities

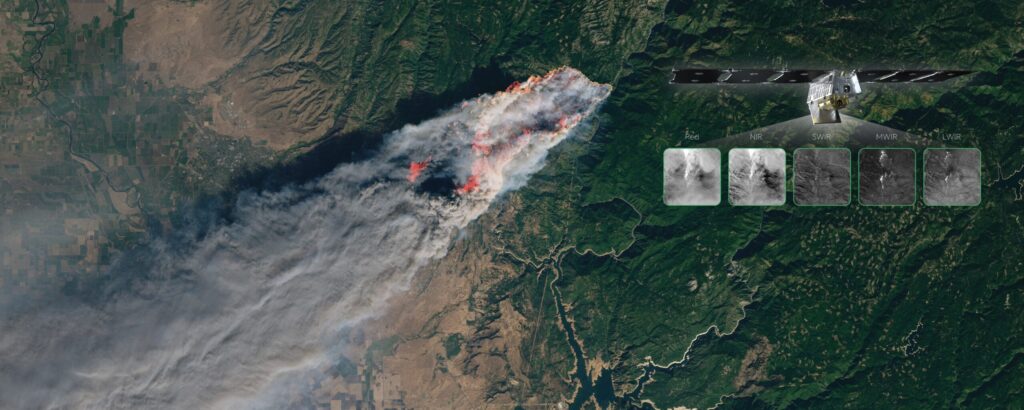

A major driver in the shifting funding commitments is the ERS-EO, short for ESA’s Earth observation component of the Earth Observation Governmental Service (EOGS). The program, backed strongly by the European Commission, aims to provide Europe with dual-use, defense- and security-tailored EO capabilities.

Poland allocated 109 million euros to the new program. For comparison, that’s more than half of the country’s total contribution at the previous ministerial in 2022.

However, the two countries did not back up the same components of the ERS-EO project. Poland invested more in the elements tied with the EOGS objectives and what is currently called Element 2 Space Resilience Nodes — a European network focused on the use and exchange of resilience services.

Spain instead committed 325 million euros for a ERS-EO cluster (national-driven initiatives within the ERS framework), specifically focused on the construction of an Atlantic Constellation, a small-satellite constellation shared with Portugal (currently called “Cluster 2 ESCA+”).

The Launcher Challenge revolution

The shifting launcher landscape in Europe — initiated with the success of SpaceX but accelerated by the 2023-2024 launcher crisis when the continent temporarily lost independent access to space due to delays with Ariane 6, the breakdown of the collaboration with Russia and the grounding of Vega-C — also shaped the outcomes of this ministerial. Spain and Poland served as examples of how emerging players are responding.

Spain committed 169 million euros to MIURA, Spain-based PLD Space’s reusable small-payload launcher which is participating in the European Launcher Challenge (ELC). Poland, meanwhile, raised its contribution to the Future Launcher Preparatory Programme (FLPP), a long-standing ESA program focused on new disruptive launcher technologies, from 3 million euros in 2022 to 48 million euros in 2025.

Europe’s launcher landscape has historically been dominated by France, Germany and Italy through Ariane and Vega. But the proliferation of smaller, alternative launcher programs is enabling countries not traditionally considered “launcher nations” to build national industrial bases and introduce fresh competitive pressure into the market. ESA’s Head of Strategy and Institutional Launches for Space Transportation, Lucia Linares, explained to SpaceNews the significance of this shift:

“The decisions on the European Launcher Challenge — joined by 10 member states — send three signals: ESA should drive the future of European launch services through more competition; it should also drive a more diverse launch services market to meet rising governmental demand; and the operational readiness of these new services must be accelerated.”

Renewed interest in long-standing programs

Both countries also increased their commitments to older programs that previously didn’t gain their attention. Poland contributed 10 million euros to the LEO PNT element (called Celeste), which it didn’t fund at all in 2022. Spain increased its contribution over threefold from 45 million euros in 2022 to 138 million euros.

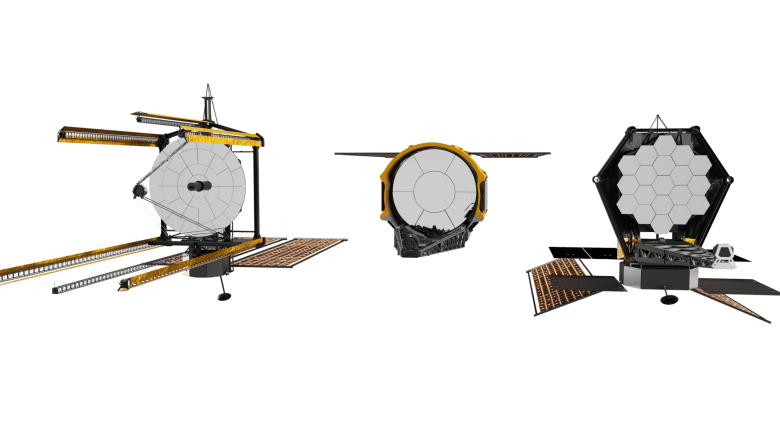

Celeste is at its initial stage and ESA plans to launch two In-Orbit Demonstrator satellites to showcase the benefits of low Earth orbit satellites for PNT. The strategic investments signal that Europe is trying to position itself as a significant contributor to the expanding LEO ecosystems, Javier Benedicto, ESA’s director of navigation, confirmed to SpaceNews.

“The strong outcome for ESA’s Navigation program at its latest ministerial council confirms Europe’s commitment to innovation and resilience in satellite navigation. The support for Celeste (LEO-PNT)” he added “marks a decisive step toward strengthening Europe’s strategic autonomy and preparing for next-generation navigation services. We are eagerly waiting for the launch of the Celeste constellation’s first satellites early next year.”

Similarly, both countries bet on IRIS2. Spain contributed far more than any other country to IRIS² Element 3, committing 140 million euros compared with France’s 60 million euros and Italy’s 79 million euros. Element 3 covers user terminals, new services and missions in low LEO, and early work on the future evolution of the IRIS² system. This contrasts with Element 1 — largely financed by France — which focuses on system architecture and early procurement.

Another development for Poland is the increase in interest in space exploration. The country’s Human and Robotic Exploration budget jumped from 12.5 million euros in 2022 to 61 million euros in 2025, 30 million of which is dedicated specifically to lunar exploration. Poland recently flew its first astronaut in decades, with Sławosz Uznański-Wiśniewski flying to the ISS on the Ignis mission, which was part of a larger commercial mission by Axiom. As commented by Domański during the ministerial “His flight not only advanced cutting-edge research, but also inspired a new generation of engineers and scientists.”

One other program which suddenly received more recognition from Spain and Poland was the FutureEO Program. In 2022, Poland and Spain subscribed 8.5 million euros and 20 million euros respectively. In 2025, these numbers rose to 35 million euros for Poland and 110 million euros for Spain. FutureEO is the ESA’s research and development program for Earth observation, focused on issues such as climate change, ecosystems collapse, human health and impact of resources consumption among the others. It is tailored to help Europe to target the Paris Agreement, the Global Methane Pledge and the European Green Deal.

Such sustained investment in Earth observation at this ministerial shows that Europe remains committed to climate science. Simonetta Cheli told SpaceNews “it’s a strong signal that member states want to strengthen scientific activities related to protecting our planet, addressing climate and environmental policies.” It’s also evidence, she said, that member states “continue to lead the way and push the boundaries of Earth observation with a competitive and innovative industry.”

Taken together, these choices illustrate how Europe’s space landscape is diverging along two vectors — security on the eastern flank and commercial constellations on the western one — while still reinforcing the same broader direction: a more security-aware, commercially competitive and multi-polar European space ecosystem.

Editor’s Note (Dec. 8, 2025): This article was originally published with an inaccurate conversion from euros to U.S. dollars. It has been corrected.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

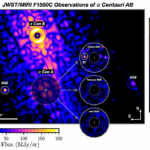

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits