Now Reading: Astronomers discover images of rare Tatooine-like exoplanet with a strange 300-year orbit: ‘Exactly how it works is still uncertain’

-

01

Astronomers discover images of rare Tatooine-like exoplanet with a strange 300-year orbit: ‘Exactly how it works is still uncertain’

Astronomers discover images of rare Tatooine-like exoplanet with a strange 300-year orbit: ‘Exactly how it works is still uncertain’

Astronomers have discovered a planet beyond the solar system that orbits its twin parent stars closer than any ever seen before in a binary. The twin stars in the sky over the newly-found extrasolar planet, or “exoplanet,” likely bear a resemblance to the twin stars over Tatooine, the home planet of Luke Skywalker, when viewers first meet the young hero at the beginning of Star Wars: A New Hope.

This exoplanet is six times closer to its parent stars than any previously directly imaged binary system exoplanet, yet despite this relative proximity, it still has a year that lasts 300 times as long as an Earth year.

“Of the 6,000 exoplanets that we know of, only a very small fraction of them orbit binaries,” team member and exoplanet imaging expert Jason Wang of Northwestern University said in a statement. “Of those, we only have a direct image of a handful of them, meaning we can have an image of the binary and the planet itself. Imaging both the planet and the binary is interesting because it’s the only type of planetary system where we can trace both the orbit of the binary star and the planet in the sky at the same time.

“We’re excited to keep watching it in the future as they move, so we can see how the three bodies move across the sky.”

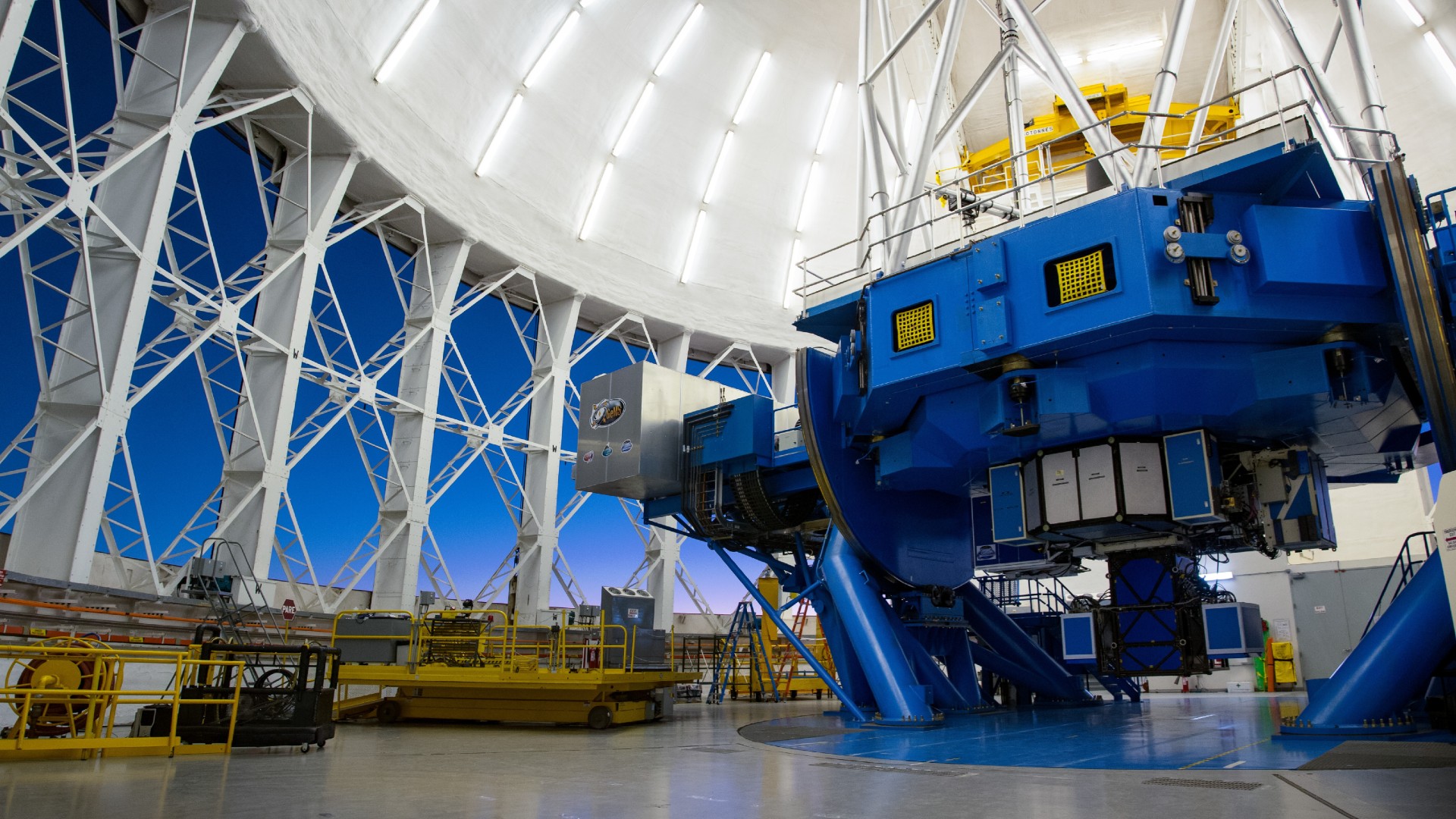

A new discovery from decade-old data

This exoplanet may be new to astronomers, but it isn’t actually a new observation. Wang and colleagues discovered HD 143811 AB b in archival data collected almost 10 years ago by the Gemini South telescope and its Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) instrument. GPI captured images of exoplanets by blocking out the overwhelming glare of their parent stars using a coronagraph, an instrument that acts almost like the artificial equivalent of an eclipse. The instrument then used adaptive optics to sharpen the images of these faint planets around their bright stars.

GPI operated from 2014 to 2022, when it was removed from Gemini South and transferred to the University of Notre Dame in Indiana to undergo a major upgrade of the whole system called GPI 2.0. Next year, once upgrades are completed, GPI 2.0 will be moved to the Gemini North telescope atop Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

This discovery came about when Wang and colleagues decided to revisit the GPI data ahead of its new life as GPI 2.0. “I didn’t think we’d find any new planets,” Wang said. “But I thought we should do our due diligence and check carefully anyway.”

“During the instrument’s lifetime, we observed more than 500 stars and found only one new planet,” Wang said. “It would have been nice to have seen more, but it did tell us something about just how rare exoplanets are.”

Team member Nathalie Jones of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA) assessed GPI data gathered over three years between 2016 and 2019, cross-referencing it with data collected by the W.M. Keck Observatory. This led to a tantalizing discovery, a faint object following the motion of a star.

“Stars don’t stand still in a galaxy; they move around,” Wang explained. “We look for objects and then revisit them later to see if they have moved elsewhere. If a planet is bound to a star, then it will move with the star. Sometimes, when we revisit a ‘planet,’ we find it’s not moving with its star, then we know it was just a photobombing star passing through. If they are both moving together, then that’s a sign that it’s an orbiting planet.”

Astronomers can determine the difference between light coming directly from a star and light being reflected by a planet, meaning they can also look at data and compare it to what it would look like if a mystery object is indeed a planet. These tests allowed Jones to determine that HD 143811 AB b is indeed a planet that was first captured by GPI in 2016 but was subsequently missed by astronomers. This conclusion was also arrived at by an independent team of astronomers from the University of Exeter in the UK.

Astronomers were also able to learn a lot more about HD 143811 AB b, discovering that this planet is a whopper, at around six times the size of Jupiter. The planet was also determined to be around 13 million years old, which may sound ancient until you consider the Earth is 4.6 billion years old.

“That sounds like a long time ago, but it’s 50 million years after dinosaurs went extinct,” Wang said. “That’s relatively young in universe speak, so it still retains some of the heat from when it formed.”

It isn’t just the planet that is relatively close to its binary stellar parents; these stars are also quite close together, taking just 18 Earth days to orbit each other. Yet, despite its proximity to the stars compared to other planets found in binary systems, HD 143811 AB b still takes 300 Earth-years to complete just one orbit.

What the team doesn’t yet understand is quite how this planet formed around its binary stars.

“Exactly how it works is still uncertain,” Wang said. “Because we have only detected a few dozen planets like this, we don’t have enough data yet to put the picture together.”

Answering this question could require the team to further study HD 143811 AB.

“I’m asking for more telescope time, so we can continue looking at this planet,” Jones said. “We want to track the planet and monitor its orbit, as well as the orbit of the binary stars, so we can learn more about the interactions between binary stars and planets.”

In the meantime, Jones intends to continue hunting through archival data to discover more planets. “There are a couple of suspicious objects, but what they are, exactly, remains to be seen,” Jones concluded.

The team’s research was published on Thursday (Dec. 11) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

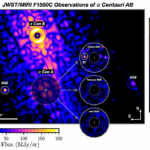

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits