Now Reading: It’s time to unburden space cooperation with China

-

01

It’s time to unburden space cooperation with China

It’s time to unburden space cooperation with China

The time is ripe to end the “Wolf Amendment,” a congressional bar inhibiting civil collaboration between the United States and China in space. The impetus for the law was noble — an attempt to challenge human rights conditions in China and prevent leaks of space-related technology — but in practice the ban harms our security and future in space. Given recent approvals to operate around the ban and NASA’s history of successful cooperation in space and modern diplomacy efforts, now is the time to allow our nation’s best and brightest in space to forge new relationships.

The Wolf Amendment came into being in 2011 and has outlived its namesake, Congressman Frank Wolf: a Republican representative from Virginia who served in Congress from 1981 until 2015. The amendment states that no government funding given to NASA, the National Space Council, or the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy can be used to “collaborate with, host, or coordinate bilaterally with China or Chinese-owned companies” without congressional approval.

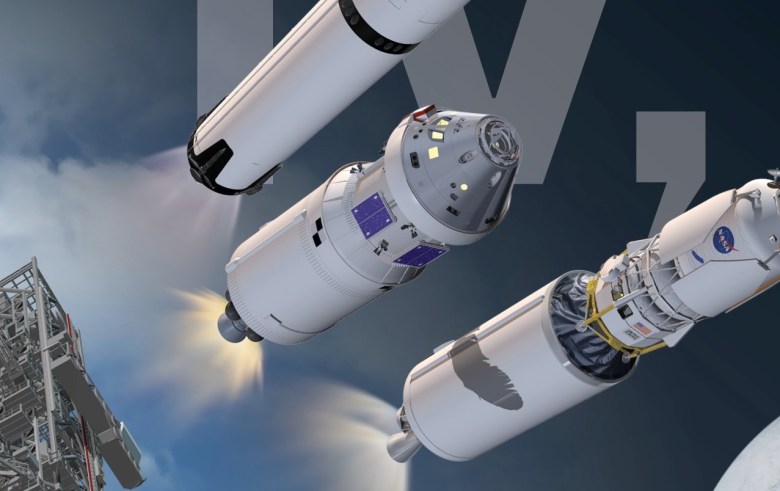

When Congress created NASA in 1958, part of its charge to the infant agency was to contribute to “cooperation by the United States with other nations and groups of nations” on work pursuant to NASA’s mission — and the agency delivers. Every time NASA collaborates, it takes a leadership role and its skillfulness as an international collaborator and leader in space shines. While there are many smaller-scale examples of this effort, possibly the most notable and celebrated is the International Space Station (ISS). Despite strained U.S.-Russia relations, the crew of the ISS orbits on.

Last year I had the opportunity to visit NASA Headquarters in Washington D.C. and see the ISS mission control center there. Scattered about the room were phones with direct lines to cooperating space agencies around the world and shared schedules displayed in multiple languages. Just that morning, staring at my phone, I read difficult news about our strained relations to Russia and the conflict in Ukraine. But here, in this room, was proof that space exploration could be a common ground for trust-building in times of tension.

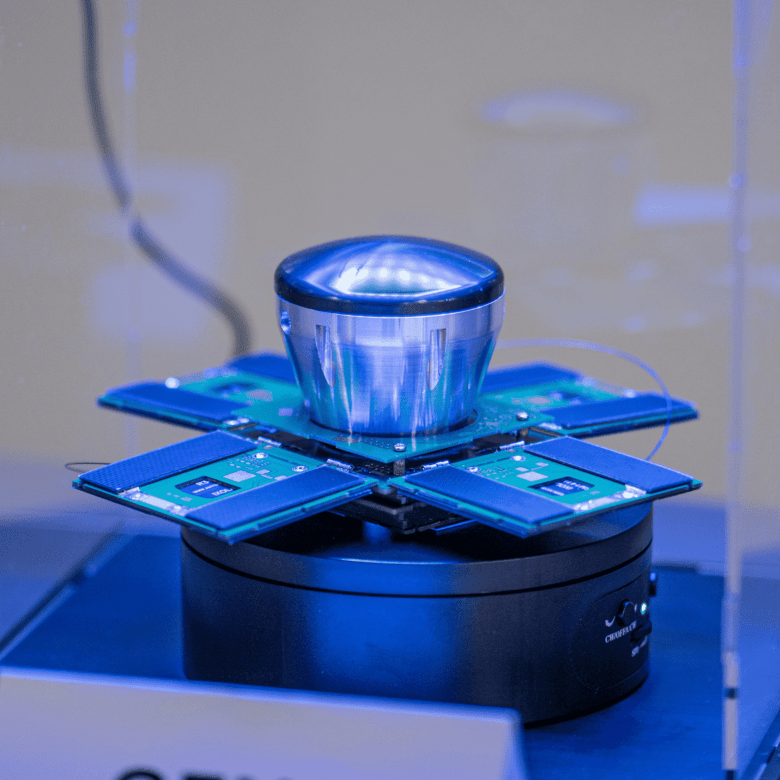

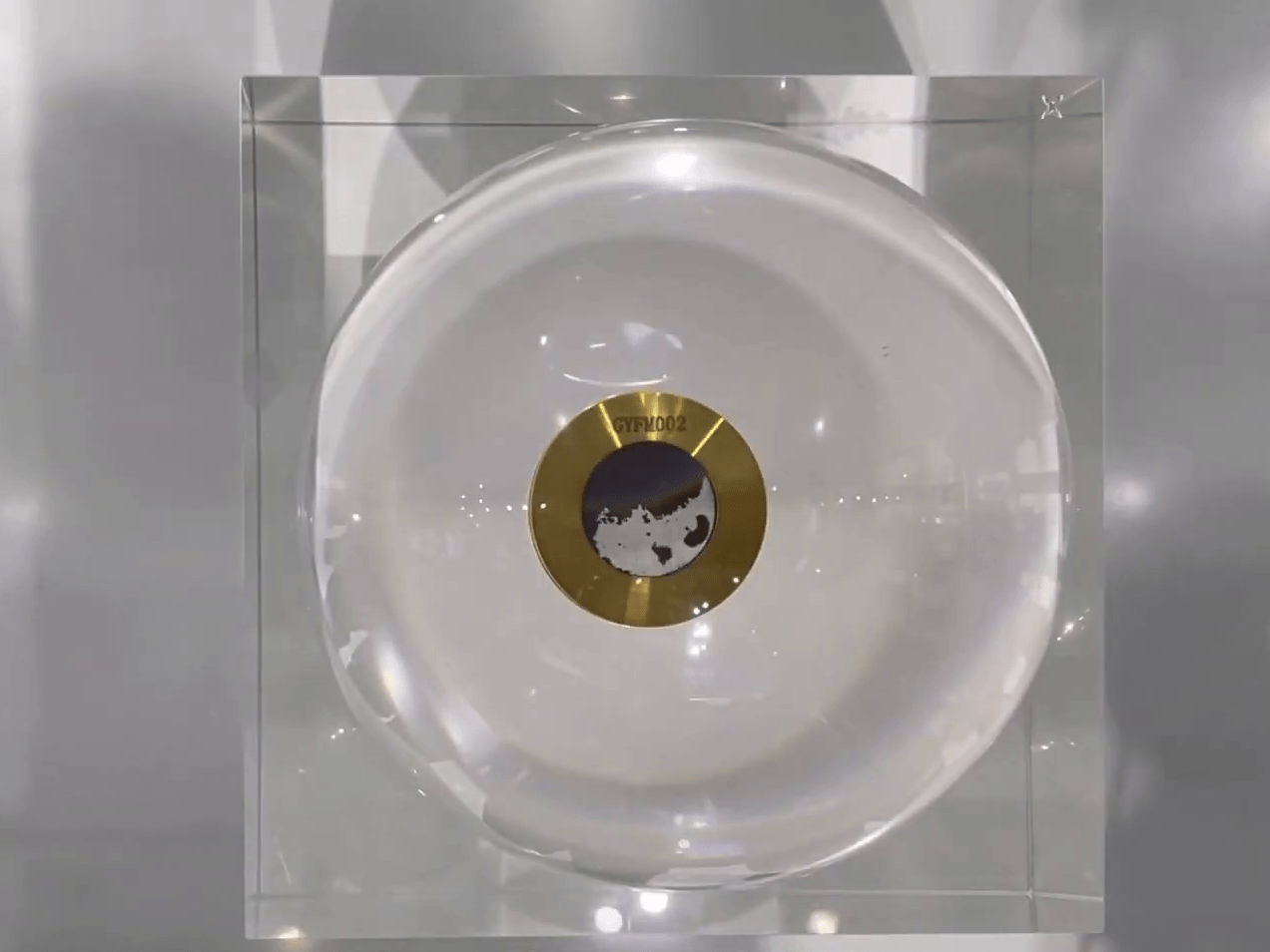

NASA seems eager to create these bridges as well. In December 2023, the agency successfully worked around the Wolf Amendment, gaining access to lunar soil and rock that China’s Change 5 mission brought back to Earth in 2020. It’s notable that other scientists already had access to the samples, as the law prevents only government-funded programs from this type of collaboration, thus hobbling the most expansive and sophisticated civil space program in the world.

While the U.S. now has gained access to these soil samples, allowing planetary scientists to compare them to U.S.-collected samples, the exchange isn’t being returned in kind. NASA has not shared Apollo mission-collected soil samples with China.

China has other collaborators. The new International Lunar Research Station is an initiative for moon exploration jointly led by Russia and China. It runs parallel to the U.S. Artemis program, which includes a series of agreements between the U.S. and other countries called the Artemis Accords. These agreements set forth legal principles regarding exploration on the moon, and the Russian and Chinese initiative aims to do the same. While the two programs are not directly in conflict, and I am not so pessimistic to believe they’ll inevitably result in conflict, the ability to sit across the table from our Chinese colleagues in these efforts would be advantageous.

Admittedly, U.S. relationships to China are not without concern — there is a lot to be thoughtful of — but keeping rivals closer only keeps us safer. There are reliable control systems for securing U.S. technology that can be used in place of this prohibition. Further, the law has done little to change China’s human rights policies or slow the growth of their own space sector.

Freedom House, a Washington DC based nonprofit, tracks fundamental freedoms and rights in countries and territories worldwide. Their score for China sits at a stable 9 out of 100 over the past four years. Meanwhile, China’s launch frequency has risen from 19 successful orbital launches in 2015 to 66 in 2024. In 2024, total investment in China’s commercial space sector exceeded 15 billion yuan. The goals of the Wolf Amendment are not being achieved.

Open lines of communication with our international peers create mutual understanding. That understanding creates predictability and trust. Predictability is critical to our future planning in a global domain like space. Building global trust ensures that our efforts in space benefit not only the U.S., but the world and the human species.

Space belongs to all, and it’s time for our nation’s finest to work with all.

Elsbeth Magilton is a U.S. space law professor at the University of Nebraska College of Law Space, Cyber and National Security Law Program.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly