Now Reading: ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission moves up launch

-

01

ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission moves up launch

ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission moves up launch

WASHINGTON — A delay in one European Space Agency mission is creating an opportunity for an earlier, and more capable, launch for another ESA spacecraft.

ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission, designed to fly by a long-period comet, had been scheduled to launch on an Ariane 6 alongside Ariel, an ESA mission to study exoplanet atmospheres. That shared launch was planned for the second half of 2029, even though Comet Interceptor is expected to be ready in 2028.

At a Jan. 14 meeting of NASA’s Small Bodies Assessment Group in Baltimore, Michael Kueppers, ESA project scientist for Comet Interceptor, said a recent schedule review of Ariel pushed its launch readiness date to the second half of 2031, leaving Comet Interceptor facing a three-year delay.

“The consequence would be that Comet Interceptor would have to be stored for three years, with the associated costs,” he said. “It’s also the difficulty of keeping teams for three years when not much is happening.”

As a result, the mission explored alternative launch options. The preferred alternative is to launch on an Ariane 64 as a co-passenger with a commercial communications satellite headed to geostationary orbit. After deploying the commercial spacecraft, the Ariane upper stage would send Comet Interceptor toward the Earth-sun L1 Lagrange point, from which it would drift to the L2 point.

Kueppers said the alternative launch plan was approved by ESA’s Science Programme Committee in December, and the agency is now working with Arianespace to identify a launch opportunity between August 2028 and July 2029.

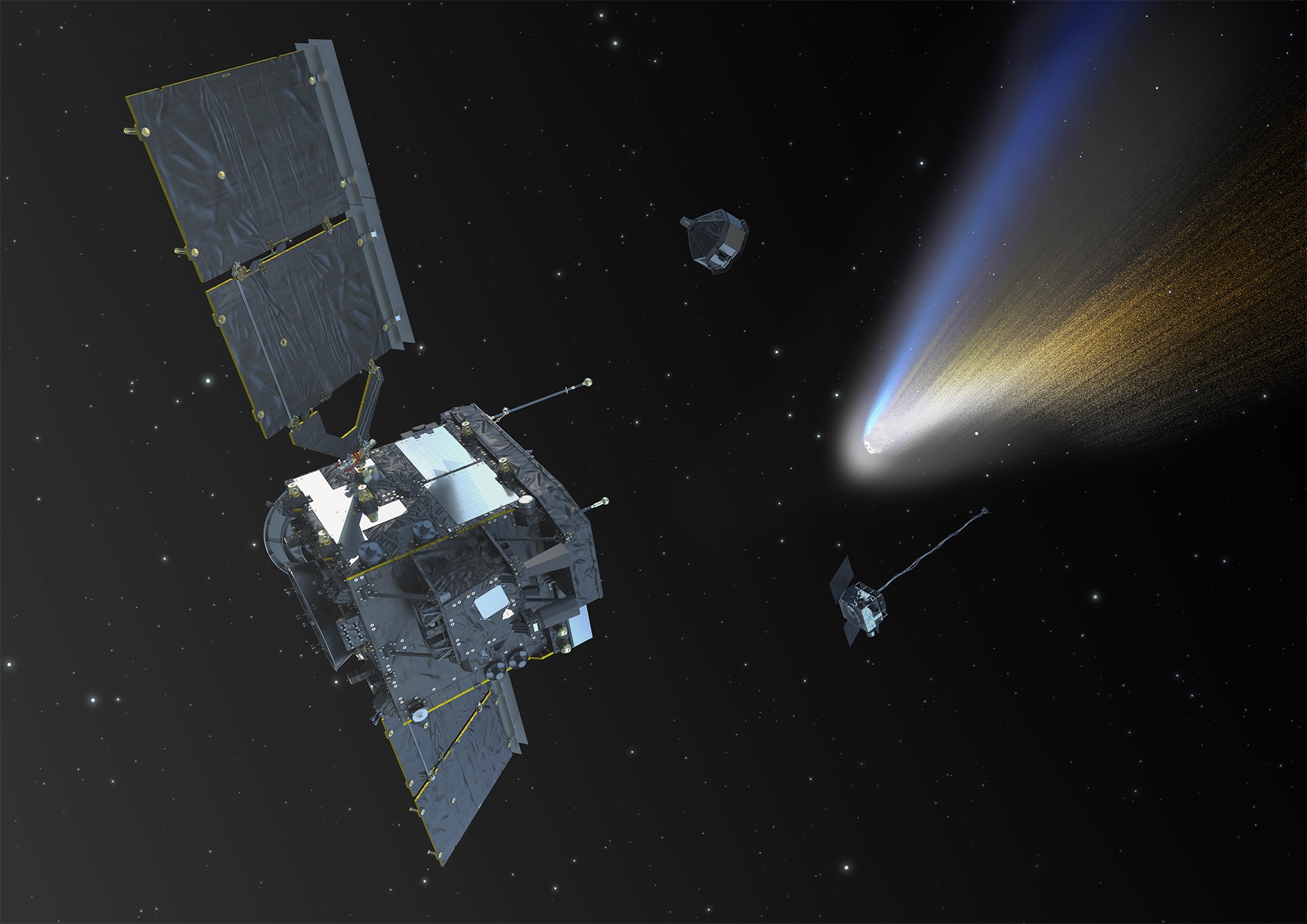

Comet Interceptor is unusual in that its target may not be identified until after launch. The spacecraft will loiter at the Earth-sun L2 point for up to several years, waiting for a suitable target. The mission aims to fly by a long-period comet originating in the distant reaches of the outer solar system.

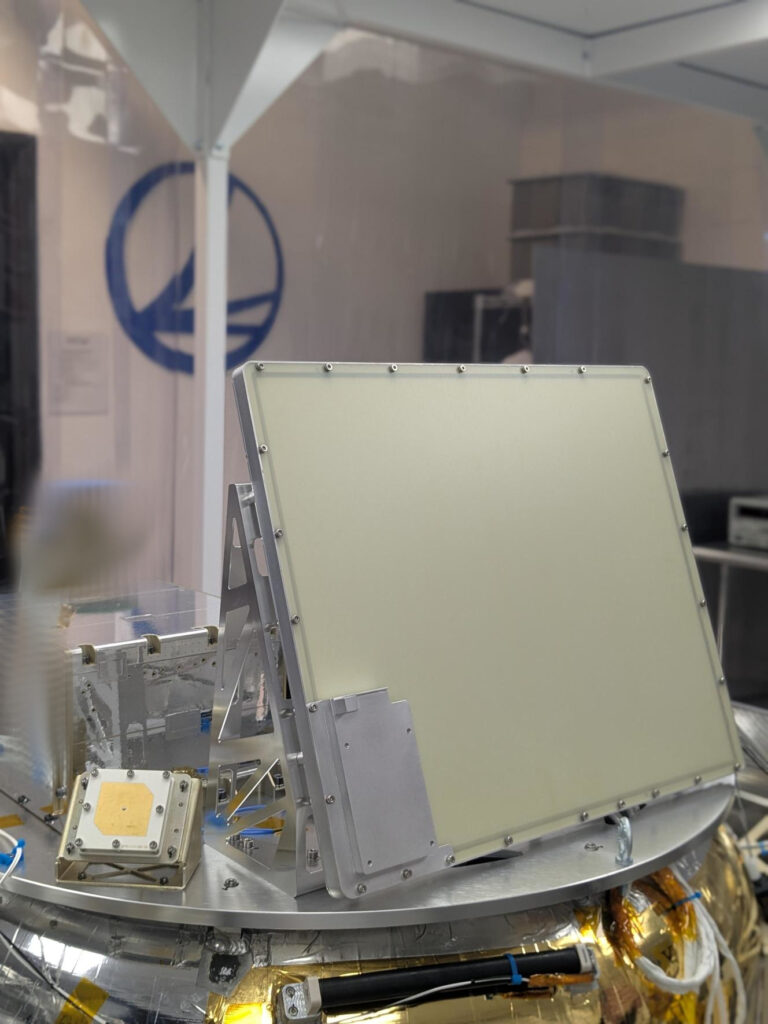

In addition to the main spacecraft, Comet Interceptor will deploy two smaller probes, one provided by the Japanese space agency JAXA, to conduct multipoint observations during the flyby at relative speeds of up to 70 kilometers per second.

“Ideally, we would get a dynamically new comet, to get a comet as pristine as it gets,” Kueppers said. An alternative would be an interstellar object such as 3I/ATLAS, but he said that was “relatively unlikely” to be discovered during the mission’s lifetime. If no suitable long-period comet is found, the spacecraft would instead target a short-period comet that has spent more time in the inner solar system.

One advantage of the alternative launch is improved performance. The delta-v, or change in velocity, available to Comet Interceptor to pursue a comet would increase from about 600 meters per second to roughly 1,000 meters per second. That improvement comes from larger launch mass available to the spacecraft in this new launch configuration, allowing it to carry more propellant.

The higher delta-v increases the likelihood of intercepting a suitable long-period comet. Kueppers said the probability of failing to find such a target over a six-year mission would drop from about 20% to less than 10%.

“The change is an upgrade from economy to business class,” he said.

That change does come with an additional, unspecified cost, but Kueppers said that additional launch cost would be at least partially offset by avoiding the three years of storage costs had Comet Interceptor kept its launch with Ariel. Depending on which mission ultimately replaces Comet Interceptor on the Ariane 6 launch with Ariel, he added, the additional cost could be fully offset.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly