Now Reading: Aboard The International Space Station, Viruses And Bacteria Show Atypical Interplay

-

01

Aboard The International Space Station, Viruses And Bacteria Show Atypical Interplay

Aboard The International Space Station, Viruses And Bacteria Show Atypical Interplay

In a new study, terrestrial bacteria-infecting viruses were still able to infect their E. coli hosts in near-weightless “microgravity” conditions aboard the International Space Station, but the dynamics of virus-bacteria interactions differed from those observed on Earth. Phil Huss of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, U.S.A., and colleagues present these findings January 13th in the open-access journal PLOS Biology.

Interactions between phages—viruses that infect bacteria—and their hosts play an integral role in microbial ecosystems. Often described as being in an evolutionary “arms race,” bacteria can evolve defenses against phages, while phages develop new ways to thwart defenses. While virus-bacteria interactions have been studied extensively on Earth, microgravity conditions alter bacterial physiology and the physics of virus-bacteria collisions, disrupting typical interactions.

However, few studies have explored the specifics of how phage-bacteria dynamics differ in microgravity. To address that gap, Huss and colleagues compared two sets of bacterial E. coli samples infected with a phage known as T7—one set incubated on Earth and the other aboard the International Space Station.

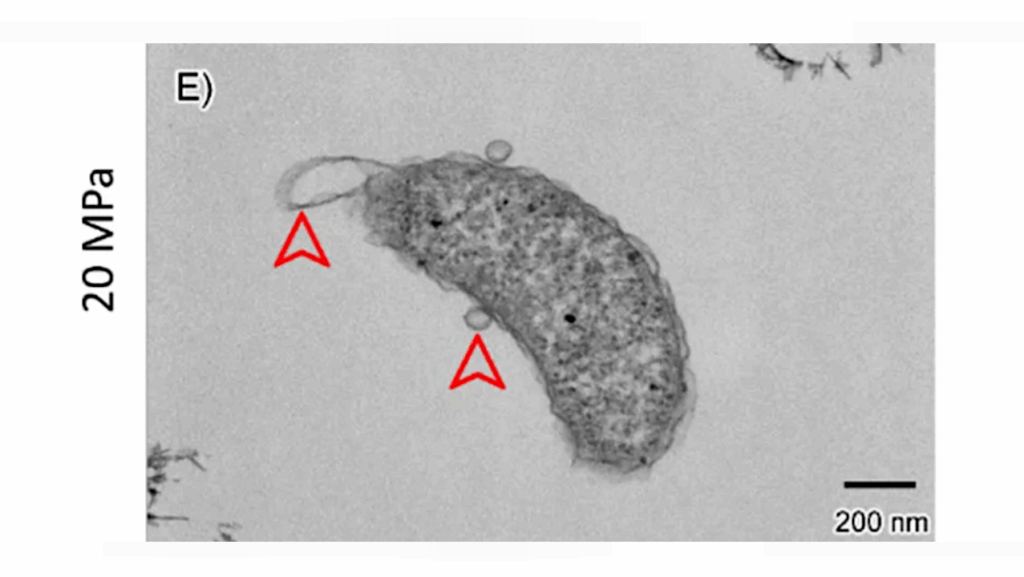

Analysis of the space-station samples showed that, after an initial delay, the T7 phage successfully infected the E. coli. However, whole-genome sequencing revealed marked differences in both bacterial and viral genetic mutations between the Earth samples versus the microgravity samples.

The space-station phages gradually accumulated specific mutations that could boost phage infectivity or their ability to bind receptors on bacterial cells. Meanwhile, the space-station E. coli accumulated mutations that could protect against phages and enhance survival success in near-weightless conditions.

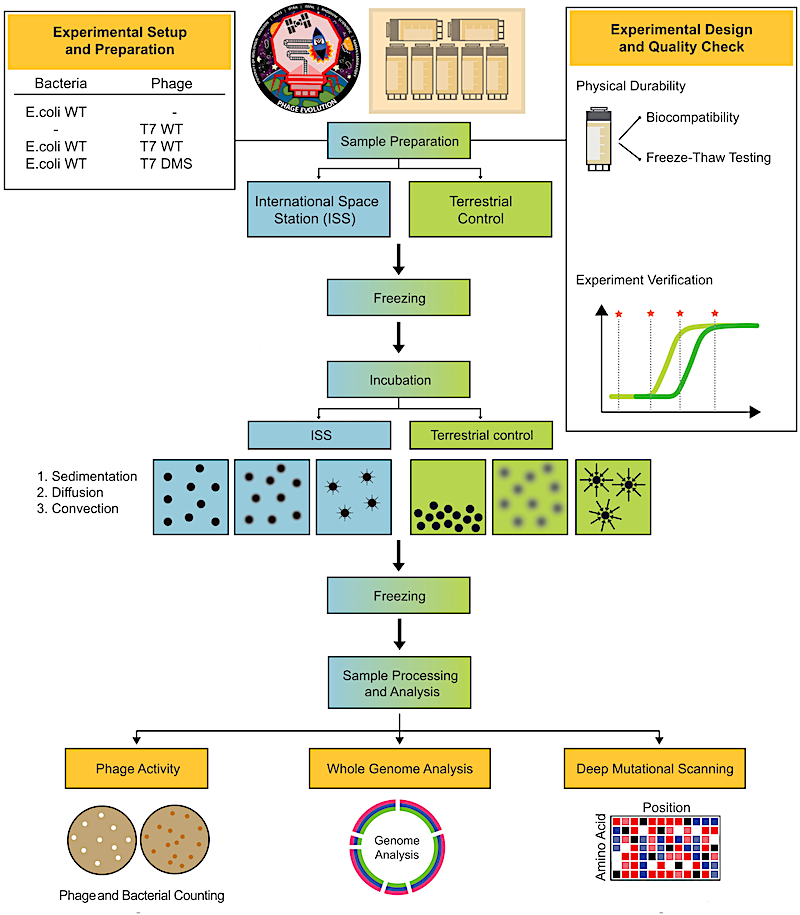

Experimental design to evaluate microgravity interactions on the ISS. Samples were prepared on Earth, with quality checks to ensure cryovial integrity and prevent leakage during freeze–thaw cycles. Identical sets were frozen, then thawed and incubated either in microgravity on the ISS (left) or terrestrially (right) for defined intervals. All samples were re-frozen and later analyzed on Earth for phage and bacterial titers, whole-genome sequencing, and deep mutational scanning of the T7 receptor binding protein tip domain. — PLOS Biology

The researchers then applied a high-throughput technique known as deep mutational scanning to more closely examine changes in the T7 receptor binding protein, which plays a key role in infection, revealing further significant differences between microgravity versus Earth conditions. Additional experiments on Earth linked these microgravity-associated changes in the receptor binding protein to increased activity against E. coli strains that cause urinary tract infections in humans and are normally resistant to T7.

Overall, this study highlights the potential for phage research aboard the ISS to reveal new insights into microbial adaption, with potential relevance to both space exploration and human health.

The authors add, “Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth. By studying those space-driven adaptations, we identified new biological insights that allowed us to engineer phages with far superior activity against drug-resistant pathogens back on Earth.”

Citation: Huss P, Chitboonthavisuk C, Meger A, Nishikawa K, Oates RP, Mills H, et al. (2026) Microgravity reshapes bacteriophage–host coevolution aboard the International Space Station. PLoS Biol 24(1): e3003568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3003568

Astrobiology,

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

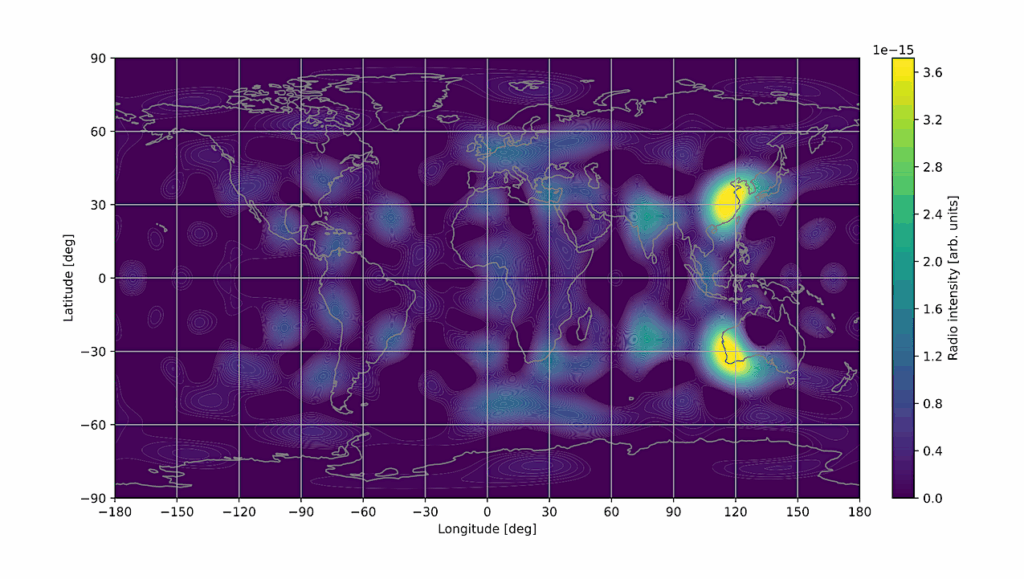

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly