Now Reading: As satellites become targets, Space Force plans for growth and a broader role

-

01

As satellites become targets, Space Force plans for growth and a broader role

As satellites become targets, Space Force plans for growth and a broader role

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Space Force could double in size within the next decade as the Pentagon increasingly treats space as a contested military domain rather than a supporting utility, according to the service’s second-highest-ranking officer.

Gen. Shawn Bratton, vice chief of space operations, said the youngest U.S. military branch is being pressed by the Army, Navy and Air Force to move faster and deliver capabilities that did not previously exist. The Space Force, established six years ago, currently has about 10,000 uniformed service members and roughly 5,000 civilians.

“I do think we will double the size, the number of people in the Space Force … within the next five to 10 year time horizon,” Bratton said, citing expanding operational demands and the need for additional infrastructure to support them.

Bratton spoke Jan. 21 at an event hosted by the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center and SpaceNews, offering a detailed look at how the service is redefining its role inside the U.S. joint force.

From enabler to warfighting partner

For decades, the military viewed space largely as a support function, responsible for operating satellites that provide GPS, communications and missile warning. That model is changing as potential adversaries expand their own space-based surveillance and targeting capabilities.

The shift is being driven as much by the other services as by the Space Force itself, Bratton said. Naval and ground commanders are increasingly aware of how vulnerable their forces are to observation from orbit.

“The other services have really pushed us to go faster, do more,” Bratton said.

That pressure reflects a recognition that satellites are no longer just enablers but integral to how wars would be fought. Adversaries’ ability to use space systems to locate ships at sea or track troop movements has forced planners to think about how those systems might be disrupted in a conflict.

The Pentagon is now focused not only on defending U.S. space assets from jamming or attack, but also on denying adversaries access to their own space-based capabilities if necessary. That approach requires close coordination across the joint force.

“This can’t be a space fight for space,” Bratton said. If an adversary’s command-and-control facility on the ground needs to be disabled, he noted, that mission would fall to the Air Force, Navy or Army.

The evolving mission has implications for how the Space Force is positioned within the military.

“I’m not just here to give your satcom and your GPS and all the stuff you get,” he said. “You got to work for me, just like I’m working for you.”

To better integrate space operations into combat planning, the Space Force is standing up components inside the military’s combatant commands. The goal is to develop a clearer picture of how space capabilities would be employed alongside air, land and maritime forces during a conflict.

Planning for 2040 and beyond

A long-range planning initiative known as the Objective Force study is now in the works. It’s an internal assessment of what the Space Force needs to become over the next 15 years and, unlike traditional planning processes tied to specific programs or budgets, the study is focused on future missions and operating environments.

Rather than asking how many satellites it might need in 2040, the service is examining what capabilities will be required and how forces should be structured to sustain operations in a contested space environment.

The study is being led by the Space Warfighting Analysis Center, an organization that Bratton said could eventually be elevated to a full command dedicated to future force design.

“We’re pulling it together,” he said, describing an effort to better understand what the Army, Navy and Air Force will need from the Space Force in the coming decades.

Some missions are unlikely to change. Missile warning, satellite communications and precision navigation and timing will remain core functions, Bratton said. The difference will be in how those missions are carried out and how resilient they are under attack.

“I think we’ll be doing a lot more space superiority activities than we are today,” he said.

Focus on cislunar space

An area poised for increased focus is the cislunar region, the vast expanse between Earth and the moon. As the U.S., its allies and competitors expand lunar exploration and infrastructure, that region is becoming strategically important.

From a military perspective, operations in cislunar space could affect missile warning, space domain awareness and the protection of satellites operating far from Earth, where monitoring and defense are more difficult.

“I need to be able to command and control spacecraft beyond the moon,” Bratton said, describing capabilities that fall within the 15-year planning horizon.

The Space Force is also watching commercial activity closely. With private companies and international partners increasingly active around the moon, the service is assessing the national security implications of that expansion.

While there are no current plans to deploy Space Force personnel in space, Bratton said the possibility should not be dismissed over the long term. “It would be tragic if that didn’t happen someday,” he said.

Rethinking how satellites operate

Another emerging concept shaping the service’s future is “dynamic space operations,” a term used by U.S. Space Command to describe a move away from predictable, fixed satellite operations.

Traditionally, satellites stay in the same orbits for years, making them easier to track and target. Dynamic operations would emphasize maneuverability, allowing spacecraft to reposition or change missions in response to threats.

What that looks like in practice remains unsettled. One of the most debated ideas is in-orbit satellite refueling. Supporters argue that refueling could extend satellite lifespans and enable repeated maneuvering. Bratton is less convinced.

Refueling, he said, does not offer the same operational benefits in space as it does for aircraft. Satellites continue to orbit regardless of fuel state, meaning refueling does not extend their range.

“It may save me a lot of money, and that may be the reason to do it,” he said. But from a military perspective, he added, the advantages have not yet been proven in wargames. One concern is that the added infrastructure would introduce new vulnerabilities.

“I have not seen in wargaming the military advantage during conflict that refueling brings to space,” Bratton said.

For now, Space Force leaders remain focused on near-term demands and the need for space superiority. But as satellites become central to modern warfare, Bratton suggested, the military’s newest service is preparing for a larger role and a larger footprint in the years ahead.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

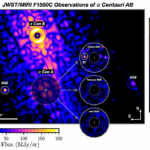

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits