Now Reading: Moon landings could contaminate evidence about life’s beginnings on Earth. Here’s how

-

01

Moon landings could contaminate evidence about life’s beginnings on Earth. Here’s how

Moon landings could contaminate evidence about life’s beginnings on Earth. Here’s how

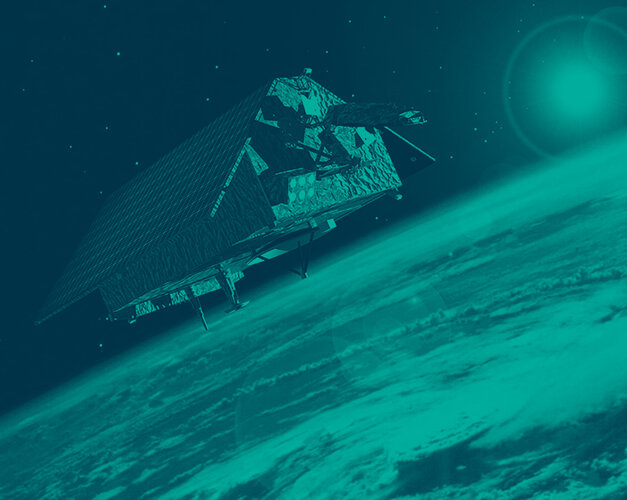

Emissions from spacecraft landings on the moon can drift freely across its surface and may settle in — and contaminate — some scientifically precious real estate, according to new research.

Many current and planned lunar landers rely on propellants that produce methane as a byproduct during the engine burns required to slow a spacecraft for touchdown.

The new study finds that this exhaust methane can spread rapidly across the airless moon and become trapped in ultra-cold craters at the poles — regions that never receive sunlight and are considered prime targets in the search for ancient water ice and organic molecules that scientists hope may reveal clues about how life first emerged on Earth.

The findings come as space agencies and private companies prepare for a new era of lunar exploration, including long-term missions aimed at establishing a sustained human presence on the moon.

Detailed in a paper published in November in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, the results could help shape guidelines to protect sensitive lunar areas and reduce the chemical footprint of future missions, the authors say.

“We have laws regulating contamination of Earth environments like Antarctica and national parks,” study leader Francisca Paiva, of the Instituto Superior Técnico in Portugal, said in a statement. “I think the moon is an environment as valuable as those.”

At the moon’s north and south poles, permanently shadowed craters remain so cold that water ice and other frozen compounds can persist for billions of years. Scientists think these ancient deposits may preserve organic material delivered long ago by comets and asteroids, including prebiotic molecules linked to the origins of life on Earth.

Unlike Earth, where geological activity and an active atmosphere have erased much of the planet’s earliest record, the moon has remained largely unchanged, making its polar ice a uniquely valuable scientific archive. Those same frigid conditions, however, also make the polar craters efficient traps for modern contaminants, the study suggests.

To understand how spacecraft exhaust might spread, Paiva and her team developed a computer model tracking the movement of methane, the most abundant organic compound produced by common spacecraft propellants.

Using the European Space Agency‘s (ESA) planned Argonaut lander mission as a case study, the team simulated methane released during a modeled descent beginning about 19 miles (30 kilometers) above the moon’s south pole. The simulations, which tracked the methane over seven lunar days, showed the molecules traveling freely across the lunar surface, rather than diffusing and dispersing, because the moon has virtually no atmosphere.

“Their trajectories are basically ballistic,” Paiva said in the statement. “They just hop around from one point to another.”

The simulations showed methane reaching the moon’s opposite pole in less than two lunar days, or about two months on Earth. Within seven lunar days, nearly 54% of the exhaust methane became trapped in polar cold regions, including about 12% at the north pole, far from the original landing site, the study reports.

“We showed that molecules can travel across the whole moon,” Paiva added. “In the end, wherever you land, you will have contamination everywhere.”

More research is needed to determine whether contaminants merely settle on the surface ice or penetrate deeper layers where pristine material may still be preserved, the study notes.

Still, the findings represent an early step toward more thoughtful mission planning, and the authors say similar modeling of future spacecraft landings could help guide planetary protection measures “for safeguarding the moon’s pristine scientific value and paving the way for a sustainable and responsible lunar exploration.”

“I want to bring this discussion to mission teams, because, at the end of the day, it’s not theoretical — it’s a reality that we’re going to go there,” study co-author Silvio Sinibaldi, a planetary protection officer at ESA, which funded the new study, said in the same statement.

“We will miss an opportunity if we don’t have instruments on board to validate those models.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

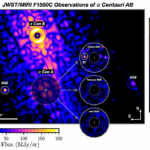

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits