Now Reading: Space Command’s case for orbital logistics: Why the Pentagon is being urged to think beyond launch

-

01

Space Command’s case for orbital logistics: Why the Pentagon is being urged to think beyond launch

Space Command’s case for orbital logistics: Why the Pentagon is being urged to think beyond launch

ORLANDO, Fla. — The Pentagon for decades has treated launch as the central logistical problem of military space. Once a satellite reaches orbit, it is expected to operate with the fuel it carries from Earth until it fails or runs dry. That model, Gen. Stephen Whiting argues, is no longer sufficient for a domain that the U.S. military now views as contested and potentially hostile.

Speaking Jan. 28 at the SpaceCom Space Mobility conference, Whiting, commander of U.S. Space Command, laid out a detailed case for building a space transportation and logistics infrastructure that would allow U.S. satellites to maneuver, be repaired, refueled and sustained in orbit — much as U.S. forces on land, sea and in the air depend on vast logistics networks to operate and fight.

The argument reflects a growing debate inside the Pentagon and Congress about whether the United States should move beyond a launch-centric approach to national security space and begin investing seriously in in-orbit servicing, refueling and mobility — capabilities that remain largely experimental and unfunded at scale.

The Space Force, as a military service, already runs the national security space launch program to ensure assured access to orbit. But Whiting said that beyond launch, the investment curve drops off sharply.

“Space forces as well have maneuver and sustainment needs, including spaceports, boosters, refuelers, servicers, maneuvering space vehicles to hunt and evade, and ready stocks of servicing and replacement satellites that can be rapidly launched over time,” he said. Those needs, he added, require a “force structure dedicated to supporting the maneuver and sustaining needs of space forces” comparable in size and scope to logistics forces in other domains.

U.S. Space Command is responsible for employing space forces in operations, ensuring U.S. and allied access to critical space-based services such as communications, missile warning and navigation, and responding to threats from adversaries including China and Russia. From that operational vantage point, Whiting said, the absence of sustainment infrastructure is becoming a strategic liability.

“While getting to space is crucial, we also need capabilities to sustain our assets once they are on orbit,” he said.

‘Tyranny of distance’

A central challenge, Whiting argued, is scale. The physical size of the space environment makes traditional concepts of sustainment difficult — but also more necessary.

“The biggest challenge for us to improve our maneuver and sustainment in space is the tyranny of distance,” he said. “The volume of space between low Earth orbit and geosynchronous orbit is 312 trillion cubic kilometers.” Trying to sustain forces across that volume without on-orbit servicing, he added, is “like sending an aircraft carrier strike group across the Pacific with only the fuel in their tanks and no way to refuel rearm or repair.”

The result, Whiting said, is not just a technical constraint but a cultural one. The assumption that satellites can only operate with the fuel they launch with “causes a psychology of scarcity in the mind of the mission planners and decision makers,” he said. “It just virtually removes maneuver from the tactical commander’s decision space.”

That critique aligns with a broader shift in military space thinking. As adversaries develop counterspace capabilities — from jamming and cyber attacks to co-orbital systems — U.S. planners are increasingly focused on concepts such as “dynamic space operations” and “sustained space maneuver.” Those terms describe satellites that can move frequently and unpredictably rather than remaining in fixed or highly predictable orbits, enabling evasion, deception and responsive actions in orbit.

Whiting framed that shift by drawing explicit parallels to other warfighting domains. The United States, he noted, has invested enormous resources to enable maneuver for terrestrial forces.

“We even have an entire U.S. combatant command, U.S. Transportation Command, that is focused on this idea of mobility and maneuver,” he said.

He pointed to the Navy’s global network of deep-water ports and its use of nuclear reactors to extend time on station, the Air Force’s reliance on aerial refueling — roughly 14% of its aircraft inventory — and the Army and Marine Corps’ prepositioned stocks of equipment and supplies around the world. All of those investments exist to ensure forces can move, fight and be sustained far from home.

Space, Whiting argued, is the outlier.

“Our opponents realize this need to maneuver and be sustained in space,” he said, singling out China’s rapid buildup of space capabilities in both quantity and diversity as “nothing short of jaw dropping.” He highlighted recent Chinese demonstrations of satellite docking and reported refueling capability.

“Dogfighting in space takes fuel, and if the Chinese are refueling their effectors, what happens when we run out of maneuver in a fight?” Whiting asked. “We cannot allow our competitors to have superior maneuver capabilities in space any more than we would allow it on land, at sea or in the air.”

Questions remain

Despite that urgency, Whiting acknowledged that his argument runs into skepticism inside the Pentagon. Many officials remain unconvinced that the cost of building space logistics infrastructure is justified, particularly when satellites can be replaced if they fail or exhaust their fuel.

The vice chief of space operations for the U.S. Space Force, Gen. Shawn Bratton, has said publicly that the “military utility” of in-space refueling has not yet been quantified and needs to be demonstrated through wargaming before large investments can be justified. Congress, for its part, has added funding in recent years for studies and limited demonstrations, but space logistics has yet to mature into a dedicated acquisition program.

There is also an expectation that commercial space companies will provide many of these capabilities. Officials frequently argue that the military should wait for the commercial market to mature before committing to large government-led programs — an approach that has slowed momentum.

Whiting said U.S. Space Command is already trying to test these concepts operationally. The command recently conducted a senior-level tabletop exercise focused on sustained maneuvering and refueling.

“This gave us insight into the required training, massing of forces, maneuver,” he said. “But we haven’t exercised holistically in this way, and one of the reasons is that we need better sustainment and logistics capabilities to enable this type of large scale exercise.”

With a nod to history, he suggested that future space-focused exercises could mirror the Army’s famous pre-World War II training events. “Rather than the Louisiana maneuvers, perhaps we should call them the Apollo maneuvers,” he said. There are no concrete plans yet for such an exercise.

Ultimately, Whiting acknowledged that the debate will come down to budgets. The Space Force faces growing demands across missile warning, space domain awareness, satellite communications and resilience, all within a constrained topline.

Sooner or later, he said, “Space Force has to make difficult budget choices, and we understand that.” From Space Command’s perspective, however, the operational demand for logistics and maneuver capabilities in orbit is already clear.

“At U.S. Space Command, we believe that that utility has been established,” Whiting said. “But obviously we’ll work with the service to continue to look at what that utility is going forward. But those investments, we think, just have to continue to grow, and the Space Force is going to need more resources.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

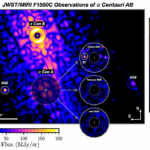

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits