Now Reading: Resurrecting Ancient Enzymes in NASA’s Search for Life Beyond Earth

-

01

Resurrecting Ancient Enzymes in NASA’s Search for Life Beyond Earth

Resurrecting Ancient Enzymes in NASA’s Search for Life Beyond Earth

NASA-supported scientists have resurrected an enzyme first used by organisms on Earth 3.2-billion years ago and, in the process, have validated a chemical biosignature in rocks that is used to understand ancient life on Earth. The research provides a new understanding of what Earth’s biosphere was like early in our planet’s history and confirms a reliable biosignature that could be used by robotic or human explorers to look for signs of ancient life on other worlds.

Nitrogen, Earth’s biosphere

The study, published in Nature Communications on Jan. 22 , focuses on a type of metabolism called nitrogen fixation, or diazotrophy. This process is what converts biologically unusable nitrogen in Earth’s atmosphere into molecules that all living organisms use to survive.

On Earth, there is a select group of organisms called diazotrophs that can perform nitrogen fixation. This group is a motley crew of bacteria (and a few archaea and eukaryotes) that are found dotted across different branches of the tree of life. Some diazotrophs are free-living organisms that fix nitrogen as they go about their day. Others are symbiotic and survive in partnership with other organisms, living in places like plant roots, lichens, fungi, and even the guts of termites and shipworms.

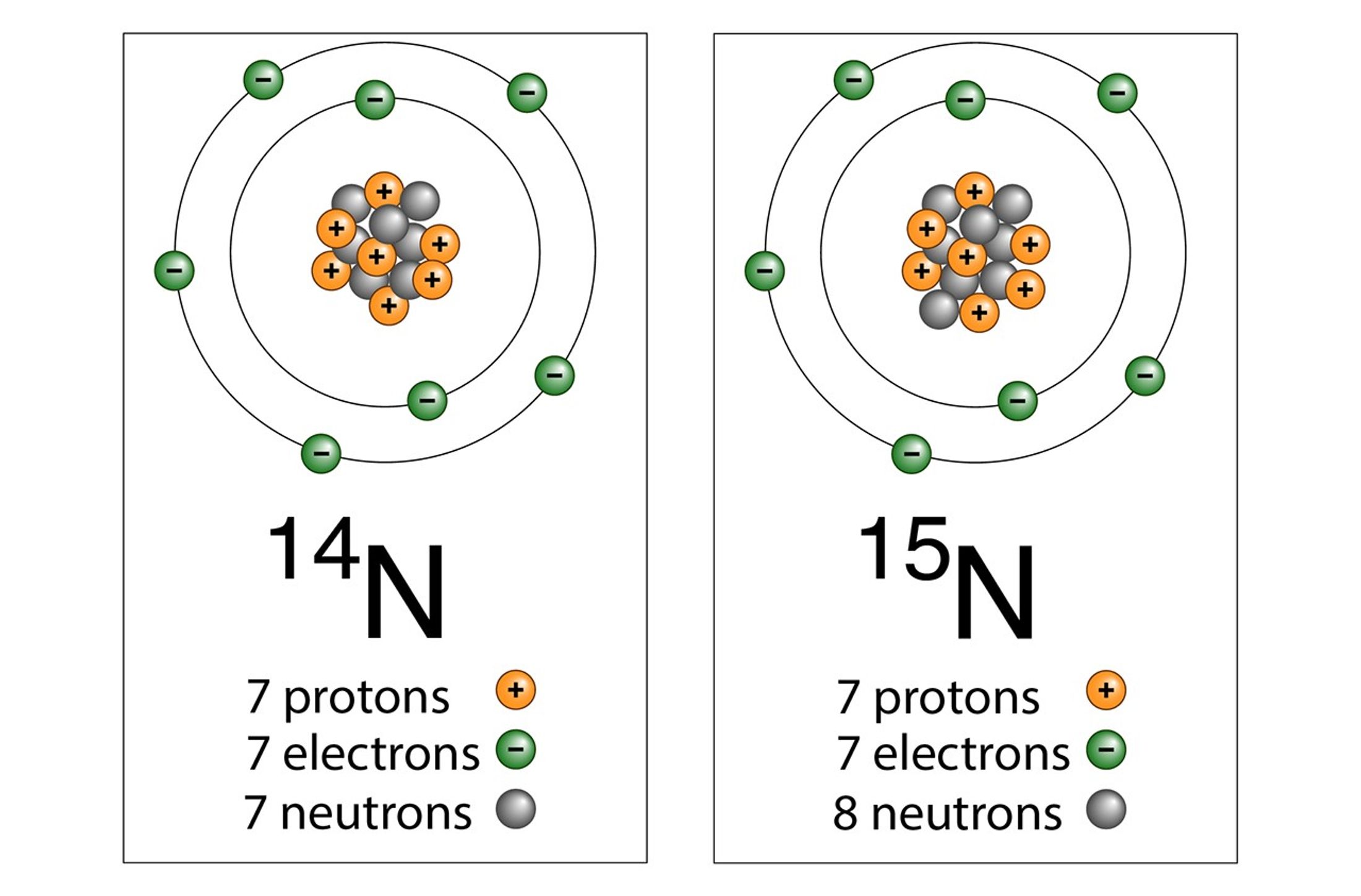

What ties this varied group of organisms together is that they all contain an enzyme called nitrogenase. This enzyme gives them the power to convert nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into compounds that are essential for building some of life’s most important molecules, such as proteins and DNA. Specifically, they convert diatomic nitrogen (N2) into biologically useful forms of nitrogen such as ammonia (NH3), thereby allowing nitrogen to enter the food chain.

In this way, every organism in Earth’s entire biosphere relies on diazotrophs to provide the nitrogen we all need to survive.

Nitrogenase through time

Because nitrogen fixation is critical for life as we know it, scientists believe that nitrogenase must have evolved early in life’s history, at a time when only single-celled microorganisms existed.

“Early life on Earth operated under conditions so different from today that it may have appeared almost alien,” said Betül Kaçar, who leads the Kaçar Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. With support from NASA, Kaçar and her team are working to understand the history of life at a planetary scale and the potential for life in the universe by rebuilding extinct biochemistries used by ancient organisms. “Studying these systems helps us understand not just where life can exist, but what life can be.”

Details about early life on Earth are obscure because the fossils microorganisms leave behind in the rock record can be ambiguous or difficult to attribute. However, when nitrogen from the atmosphere is fixed, it is slightly altered in a way scientists can recognize. The isotopic signature of the nitrogen atoms within the diazotroph is changed. Over time, as the microorganisms die, this altered nitrogen gets incorporated into rocks. Sediments are laid down, become buried, compressed, worn, and churned through the ages of the Earth. Yet even after billions of years, scientists can still identify the N-isotope biosignature left by ancient diazotrophs in the geological record.

By looking at the N-isotope record, scientists can thereby estimate when nitrogenase enzymes first appeared.

Building ancient enzyme

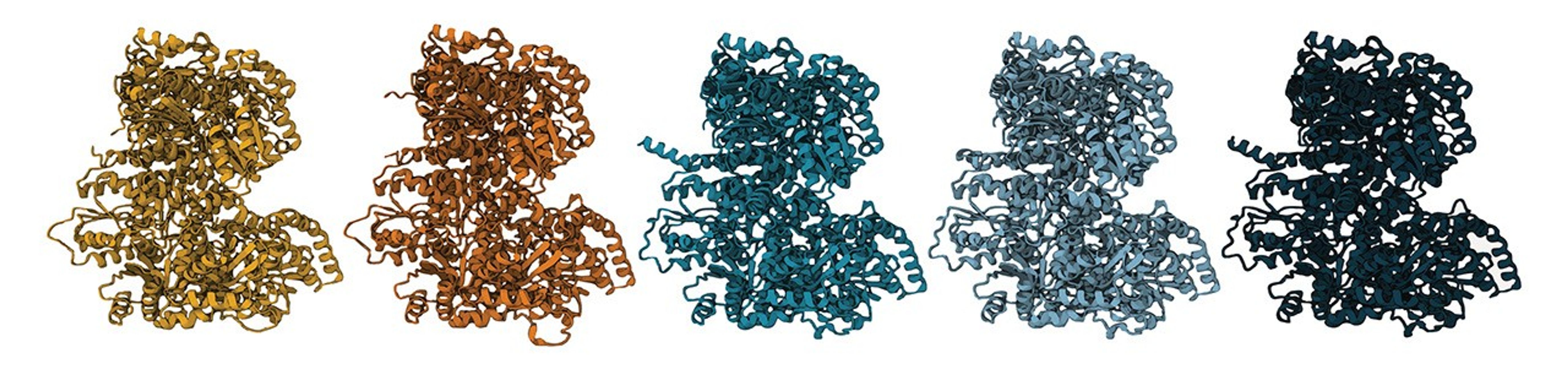

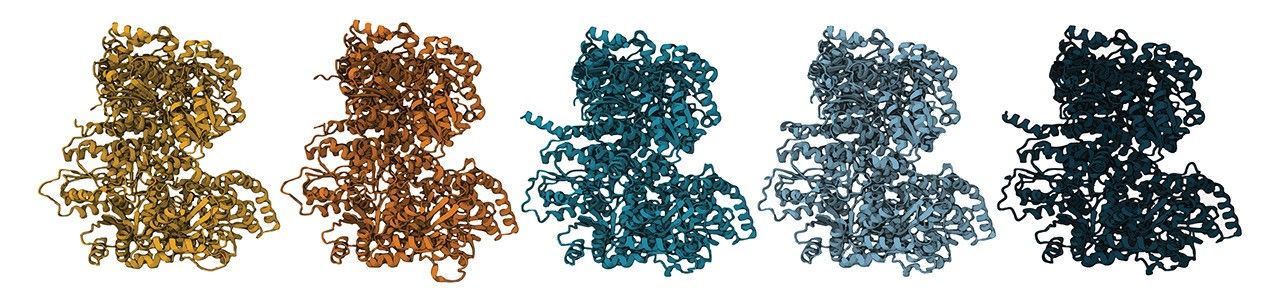

Questions about the accuracy of using N-isotopes as a biosignature have been raised in the past. Like life itself, enzymes evolve over time. As environmental conditions on Earth change, enzymes are altered at the molecular level in response. The original nitrogenase was likely smaller and less complicated than the version we see in organisms now. This means that the N-isotope signatures left behind by ancient nitrogenase enzymes could be different than the ones we see today.

To solve the question of whether N-isotopes can indeed be used as a robust biosignature, the team used synthetic biology techniques to resurrect possible ancient versions of the enzyme. They reverse-engineered modern nitrogenase, peeling away layers of evolution to reveal simpler versions of the enzyme that might have existed long ago.

The behaviors of the older versions of the enzyme were then observed when they were inserted into living microbes. What they found is that N-isotope signatures have remained the same for billions of years. The results prove that the isotopic signatures of nitrogen fixation in Earth’s oldest rocks do indeed reflect the activity of early life.

“As you step back in time, the DNA sequences of these ancient nitrogenases are very different than modern nitrogenases,” said Holly Rucker, a doctoral candidate in the Kaçar Lab and lead author on the paper. “We also see that the enzyme structure varies with age. Yet we find that despite these sequence and structure-level differences, these ancient enzymes still do the same chemistry as their modern descendants.”

The collection of synthetic genes created by the team also represent different versions of nitrogenase that would have existed over a span of two billion years of evolutionary history. This has helped fill in gaps of knowledge about how nitrogenase has changed over time, and what ancient nitrogen fixers were like.

“This research reveals how robust nitrogenase (and its associated N-isotope signature) are to change, at both an enzyme sequence level and at the planetary environment level,” explains Rucker. “The fact that the ancestral nitrogenases produce the same isotopic signature throughout billions of years of molecular tinkering, and in the face of drastic changes to the Earth’s environment, really highlights the potential of N-isotopes as a biosignature. Another key aspect of this work is that it provides further validation of our interpretation of the most ancient nitrogenase signatures in the rock record on Earth, which is important for understanding the timing of when critical metabolisms like nitrogen fixation emerged on Earth.”

Because nitrogen fixation is such an important part of biology on Earth, the research could also provide clues in the search for life beyond our planet.

“If we want to recognize life beyond Earth, we can’t limit ourselves to life as we know it today,” said Kaçar.

Nitrogenase, search for life

Now that scientists have validated the use of N-isotopes as a biosignature for ancient life on Earth, the same technique could potentially be used on other rocky worlds.

“Validated biosignatures like nitrogen isotopes give us a powerful tool for planetary exploration and access to lost biological histories” said Kaçar. “If similar signals are found on Mars or other rocky worlds, they could point to ancient metabolisms that once supported life under very different conditions. Studying these systems helps us understand not just where life can exist, but what life can be.”

For more information on astrobiology at NASA, visit:

https://science.nasa.gov/astrobiology

-end-

Karen Fox / Molly Wasser

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1600

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / molly.l.wasser@nasa.gov

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

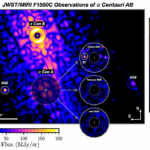

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits