Now Reading: The future of the Space Force in a competitive, congested and contested space environment

-

01

The future of the Space Force in a competitive, congested and contested space environment

The future of the Space Force in a competitive, congested and contested space environment

In this episode of Space Minds, Mike Gruss sits down with a panel of experts at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center to discuss the future of the United States Space Force. He’s joined by Susanne Hake from Vantor, John Plumb from K2 Space and Dennis Woodfork from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab. As part of an event at the Center’s Discovery Series, they explored the problems congestion on orbit creates, where the Space Force needs to focus next and possible application for AI.

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Transcript

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Voiceover: This is Space Minds from SpaceNews. In this episode of Space Minds, Mike Gruss sits down with a panel of experts at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center to discuss the future of the US Space Force. He’s joined by Suzanne Hake from Vantor, John Plumb from K2 Space and Dennis Woodfork from Johns Hopkins University. As part of an event at the Center’s Discovery Series, they explored the problems congestion on orbit creates, where the Space Force needs to focus next and possible application for AI.

Mike Gruss: Thank you, Sibel, and thank you, Paige, and thanks to all of you. Welcome. Um, I’m excited for the discussion this evening, and we have a great panel to talk about the Space Force. Um, I’d like to introduce them just briefly. Uh, Dennis Woodfork, a missionary executive for National Security Space at APL, uh, Susanne Hake, Executive Vice President of Vantor and John Plumb, Head of Strategy at K2 Space. Um, I think one way to understand the Space Force, or maybe the, the need for a separate service, is this idea of the three Cs that we just heard Sibel mention. That space is contested, congested, and competitive. Contested, generally, we’re talking about China and Russia and the development of weapons that could be used in space. This morning, the Atlantic Council released a report about Russia’s likelihood of using a weapon in space. Um, contested, or I’m sorry, congested. There are a few recent examples here, including Spanish satellite, the Chinese space station vehicle, that both appear to have been hit by debris. Competitive, we see nations and increasingly industry vying for dominance. Um, so let’s start and talk about which of these worries you the most, and what’s the solution, or more appropriately, a, a realistic path to a solution? Dennis, let’s start with you.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah, sure. Thanks again for having me, and thanks to Space News and Johns Hopkins University for putting on this event. So, um, uh, you know, I think the, the contested nature of space, uh, does give us pause. At APL, uh, we’re worried about that every day, and, um, trying to establish ways, technologies, partnerships, um, how do we accelerate industry’s ability to help with, um, the Space Force’s, uh, mission of space superiority? And so the, the contested nature of space, um, is accelerating, right? And so you don’t– not only have, uh, the, um, you know, China is putting up their own PLEO constellation because they wanna make sure that they have that advantage, but as we extend out and we get to 2040, right, the contested nature of the cislunar regime, I think, demands new technologies, new ways of thinking, new… We’ll talk about deterrence. Um, I think that’s what worries me the most, and, and how we get, uh, how we– the solution is probably looking at our ability to operationalize, um, that domain, uh, faster and establish these norms so that we can est– we can have the ecosystem that is, um, advantageous to us in deterring, um, our adversaries.

Mike Gruss: Susanne?

Susanne Hake: Um, good. Well, thank you so much for having me as well, and to keep it interesting, I’m not gonna pick the same one. Um-

Mike Gruss: Thank you.

Susanne Hake: Which leaves you in a tough spot. [laughing] Uh, but I’m gonna go with congested. Um, I think, you know, congested really has the potential to turn, you know, competition into conflict. And you can think about, you know, everything that’s going on in space right now. There’s… VCs are investing a ton of money into the defense tech community and space in particular. With the cost of launch going down, right, we have so many more companies launching things, and there’s more satellites, there’s more proximity operations, there’s just so much more going on. Um, and as there’s more, you know, satellites in space, that’s when miscalculations can happen, and they can be interpreted or misinterpreted as potentially hostile activity. And so when I think about sort of the challenge of c- uh, congested space, it’s really about how do we bring that awareness to what’s in space, and what, what are those other things? You know, how are we characterizing them and understanding them? Um, and I think that’s where some of the potential threat can happen, when there’s really a misunderstanding or lack of understanding of what’s around you.

Mike Gruss: Do you see that in day-to-day operations now? Is that congestion, or how is that congestion affecting your day-to-day operations today?

Susanne Hake: Yeah, I mean, as a– so for Vantor, we’re a company that operates satellites. Um, we have ten EO satellites in space, and, you know, for us, we put a lot of work into understanding what’s around us, being able to maneuver from other satellites or debris. And then, as a company, we also develop capabilities for Space Force and many other customers for them to understand space s- situational awareness, too.

Mike Gruss: Great. John?

John Plumb: All right, well, I’m not gonna choose competitive, so… [laughing] Uh, look, I actually think it’s interesting. First of all, everyone has their own Cs. I’ll get to mine at some point today. But, uh, the contested part-

Mike Gruss: Don’t tease us. Tell us, tell us.

John Plumb: No, uh, you know, I had– when I was ASD, I had, uh, space classification, space control, space cooperation and commercial space. So I went, I started with three, I ended up at four. It’s fine. Uh, but these are traditional. It’s good. Uh, here’s what I would say: the contested part is the thing that I think most national security minds think about, uh, but the reason– one of the reasons it’s so challenging is because of the growing congestion, right? So in a very sparsely occupat- occupied space, uh, a contested environment where China uses a ASAT against one satellite, uh, would only have effect on that one satellite. But right now, we saw even that one test they did a few years ago, it, it has effects that go through all countries, all orbits, uh, challenges human space flight. And so there’s this question, there’s this balance of the contested environment, and how do you operate in that as a military, uh, when the aftereffects are so much different than they are in any other domain? And so I think that’s the thing that’s, uh-… uh, really keen. And I will just say on one of the problems on the contested side, uh, coming from a startup satellite company here, K2 Space now, is the, the understanding that we need to move faster with commercial is there. I feel like that is a well-understood problem set. How to actually do it and how to get rid of all these legacy big R requirements, little R requirements, and non-requirements that are just hurdles, uh, is a, is a, is a heck of a challenge.

Mike Gruss: I’m curious more about your other three Cs. What– why did you develop that? Or what, what’s wrong or what has evolved from those original three Cs?

John Plumb: So I, I would say that the– [chuckles] okay. So the way to think about national security space is to think about space as a domain that is a little bit different because your satellite just doesn’t operate over your territory, right? It– Once you’re in space, you’re going over the entire planet, right? All of the satellites are going over the entire planet. Uh, and so you have this issue with the, the congested piece is really a problem. Okay, but how do you operate from a national security standpoint? The biggest challenge to everyone in this room that wants to do national security, whether they’re from the United States or from an allied country, is our classification barriers are miserable. They’re miserable to even cooperate within the Space Force. They’re harder to cooperate with the Space Force and with other surfaces. They’re hard to cooperate between different forms of warfighters, and they’re almost impossible to cooperate between, uh, new entrants to industry, uh, or, or with allies and partners. And it really limits the US and allied ability to move faster on national security, uh, at a time when China just keeps rising in prominence, and how do we counter that collectively? And it requires, uh, knocking down these classification barriers. And it’s really, really hard, and the reason you know it’s hard is that you can have secretaries of defense, you can have deputy secretaries, you can have DNIs all say, “Go fix this thing,” and it doesn’t get fixed. It’s just– It’s like this… The frozen middle doesn’t begin to describe how hard this problem is.

Mike Gruss: Dennis, did you have anything you wanted to add there? Because I saw you nodding your head.

Dennis Woodfork: Well, no, I, I… Well said. Obviously, he, uh, um, the, the years he spent trying to change that, um, you know, are laudable, and I know still there’s more work to be done there. I was gonna take a crack at the competitive nature, and I, I think from, uh, a, a competition standpoint, uh, you know, we, we talk about it as a challenge, but I think for this country, the competition is actually our asymmetric strength against, uh, adversaries like China, right? So we want space to be competitive in a way because you want these companies to be innovating and unleashing that innovation for the benefit of this country, for space superiority and economic vitality, right? And so that, that’s the other C for you.

Mike Gruss: Good. Thank you. For completionists.

Um, I, I wanted to ask about this, the single biggest change in the space operating environment that the Space Force is, is maybe not prepared for yet. I mean, we talked about classification not changing. What is, what is something that is maybe either changing faster than expected or that the Space Force needs to, to think harder about? Susanne, I’ll start with you on this one.

Susanne Hake: Yeah, I think, um, you know, I was, I was having a hard time coming up with a single thing, to be honest, but I was really thinking about just how the overall operating environment is changing so quickly and the need for kind of an increased understanding at speed, right? The operational environment is changing rapidly, um, and decisions now need to be made within, you know, seconds. And so really thinking about for everything that’s going on in space, how do we move data quickly? How do we move processing into space or faster into the ground? Um, and how do we really think about that decision speed timeline? Because once… If, when, once something happens in space, there’s seconds, you know, to understand what’s happening, make a characterization, a decision, and potentially take an action.

Mike Gruss: And, and help me out. How’s that different from five years ago, ten years ago, twenty years ago?

Susanne Hake: I think because you’re also adding in the complexity of the congestion that we’ve talked about, that you need to be able to make a decision even faster because the impacts of the decision you made can have even, you know, further impact on everything, right? There’s so much of our daily lives revolve on, in things going on in space, right? GPS satellites, stoplights, banks, ATMs, all those things are reliant on different space-based activities, and so any kind of maneuver or action in space can have a really large impact. So I think it’s that, like, combination of the congestion and that need for speed that changes things.

Mike Gruss: That’s good. John.

John Plumb: Sure. Actually, it’s excellent point. I was just gonna think, you know, twenty years ago, very different than what it looks like now. A few satellites in Geo, a couple of things here in LEO, whatever. But now, I mean, LEO is getting incredibly complicated, I think would be a fair way to say it, uh, and the ability to conduct effects in space is becoming more democratized among nation-states. Uh, so I think it’s really challenging. Uh, when– but when you say, what’s the one thing, uh, in my mind-

Mike Gruss: Or a one thing.

Plumb: Yeah, a one thing.

There is no one thing. The thing we’re definitely not prepared for is a nuclear weapon going off in space. One hundred percent, we are not prepared for that. No one is. Uh, I think in some weird way, the fact that China has built such an arsenal of satellites or fleet of satellites, if you prefer to think in a more forgiving term, um, provides one of the best deterrence to that type of use because now it wouldn’t benefit just… It would, it would damage more than just one side of whatever kind of cold war we might be in right now. But it is– we are not ready for that type of thing, and that’s really dangerous because a nuclear weapon is available to more states than just China or just Russia, and so that’s a really dangerous place to be.

Mike Gruss: This was an idea that was talked about, or it’s more than an idea, but this was talked about a lot two summers ago because there was, there was talk that Russia was developing this. But what has changed since then to the… Or what have you seen that made me– that made you think, “Hey, the Space Force is maybe a little more prepared for this, or is thinking about this in a different way?”

John Plumb: … is more prepared for it? I mean, they’re certainly thinking about it and treating it seriously, and, you know, this is an unclassified conversation, but you asked the question: What are we not prepared for? We are not prepared for that, as a society, let alone as a Space Force.

Mike Gruss: Dennis.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah, so that, that would’ve been my answer, too. So I’ll, [chuckles] I’ll go to, uh… I, I think we’re, you know, the, the, the future operating environment of humans, you know, transiting back and forth to the moon is the thing that I’m not sure, right– Well, I know there are things that we’re gonna find out, technologies that need to be invented. Um, and so, you know, the Artemis II is gonna happen ho- hopefully next month, knock on wood, and that’s gonna- that’s the next era, right? The, the first, you know, new space-age era was 2007 with the ASAT, um, test that China did, and, and that got us into this whole space is not benign, it’s a war-fighting domain. I think the next era is: Okay, we’ve got humans transiting back and forth, and there’s infrastructure needs, there are security, economic, um, uh, well, economic needs and security needs that, um, the Space Force is gonna be absolutely a part of that, right? And making sure that that ecosystem, um, is secure, much like the Navy does for, um, our seas. And so I think that’s the thing that they need to be ready for in, in this coming, coming decade.

Mike Gruss: Are you seeing signs that that’s being talked about or discussed in a, in a way you’re feeling more comfortable about?

Dennis Woodfork: Yes. So, uh, Lieutenant General, uh, retired John Shaw, I think, coined the term dynamic space operations. I think, um, his thought leadership has started a, a lot of people thinking about that, right? And what does that, what does that actually mean? It means that you’re, you’re not thinking about launching a satellite to a position and holding that position forever, right? Like we do in Geo. Um, you’re really now thinking about: How do you maneuver in a domain where you have to have logistics, you have to worry about command and control long distances for, um, uh, and, uh, long distances for communication and protection? All of those things, you have to now think about, PNT, those kinds of things. So I think when he started those conversations, and, and people are starting to write papers, I think now we’re starting to think about that. A-APL’s been doing a Cislunar Security Conference for the last few years, where we talk about this, so I do have hope that we’re gonna get there.

Mike Gruss: Yeah. And, uh, quick plug for SpaceNews. I know there’s a story this month about 2026 will be the year of more dynamic space operations.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah.

Mike Gruss: Um, let’s do a quick lightning round here. Uh, John, we’ll start with you. What is one emerging space technology– Just o- what’s one, it doesn’t have to be the one. What is one emerging space technology do you think is most underappreciated?

John Plumb: I personally think the emergence of, uh, high bandwidth direct-to-cell phone Satcom is underappreciated. It is coming. It’s actually coming faster than, uh, anyone appreciates, even when you take that sentence into account. Uh, and so I think that is going to change, uh, all sorts of national security problem sets, if any cell phone has kind of reliable Satcom. That is a very new problem set, and I think it makes space superiority very difficult.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah.

Mike Gruss: Dennis.

Dennis Woodfork: Uh, I think, uh, the ability to communicate between constellations, between, um, networks, um, is an underappreciated technology. Uh, APL just helped launch, um, uh, the Polylingual Experiment Technology, where it’s a software-defined radio that can connect between LEO, MEO, GEO, the, the ground, but also connect, hop between networks that commercial, government… I think that’s underappreciated because in the future, right, we talk about space superiority, it’s about being able to connect and, and close those kill chains. And so I think that’s something that we ne- need to watch, is the ability to make sure that our packets get from A to B, and they’re assured, and we know that they’re ours, and that they– we can use those, uh, in ways to our advantage.

Mike Gruss: Great. Susanne?

Susanne Hake: Yeah. Have we been up here for 20 minutes, and no one said AI yet? Okay, just checking. [chuckles] I won’t use that for my answer, though. Um, but-

Mike Gruss: We’ve got an AI question coming. Don’t worry.

Susanne Hake: Okay, okay, just checking, um, ’cause that s- felt like a necessary response. Um, so a slightly different take, I think one of the things that’s really top of mind is cyber resilience. Um, so, you know, the space systems are more software connected and software defined. Being able to protect them from cyberattacks is gonna be really important. Um, and that’s thinking about, you know, detecting anomalies and maintaining control of your satellite during a cyberattack, and even be able to continue your mission. So I think the kind of cyber resilience and that-those related capabilities are increasingly important.

John Plumb: If I could just jump in there, I think that’s a great point, Susanne, and I think one of the issues about trying to integrate commercial solutions, uh, better into the Space Force or better in the military services is this issue of cyber hardening. And are they going to be available in an actual conflict, or are they already compromised? Now, you could also argue that for, you know, military systems bought through legacy, uh, acquisition channels, but this is a real concern because that changes, uh, kind of the warfare piece. And I think making sure that we both have a real deep understanding of how to defend in depth, and also, you know, on the offensive side as well from cyber, is a very important part of, uh, warfare now.

Mike Gruss: All right, one more quick lightning round question here, which is, uh: One threat to the space environment that you think deserves more attention? Susanne. Sorry.

Susanne Hake: Um, yeah, no, you’re good. Um, so I touched on this actually a little bit in my opening, um, comment about the congestion, but I really think kind of this concept of ambiguity in space and how the ambiguity of understanding who’s around you, what their characteristics are, and what their capabilities are, is just going to create a lot of potential threats.

Mike Gruss: Okay. John?

John Plumb: … So what’s a threat? Say that again.

Mike Gruss: Yeah, one sped– one threat to the space environment that you think deserves more attention.

John Plumb: Outside of the nuclear piece, um. [laughing]

Mike Gruss: That can be a good answer.

John Plumb: No, that’s all right. Look, I think it is a manyfold problem, and so if you’re doing it for a specific technology, one, I start to get uncomfortable talking, uh, from a classification standpoint, but I would just say the ambiguity piece could be built into this, frankly, Susanne said, but the idea of, uh, threats from anywhere, uh, is, is an interesting problem set. And I think-

Mike Gruss: As opposed to just a few.

John Plumb: Just a few, you know, a couple known sites with a, you know, a order of battle of a couple missiles. That’s a thing of the past. These are gone. And so one of the solutions that the, uh, department’s pursuing, of course, is how do you proliferate across different orbits to try to minimize the value of an attack from any one type of threat, uh, and ideally figure out a way that you can operate through those types of attacks to kind of keep– continue to deter that type of conflict in space below, at least below the level of a, you know, World War III. You’re trying to keep the, you’re trying to keep the pressure down so that, uh, these attacks do not add value and instead are negative, and so how do you do that? It’s a really hard problem, and it continues to grow as there’s more and more satellites. N– to say nothing of, what’s the difference between a national satellite and a satellite operated by Vantor or by K2 Space, right? Is that an American satellite? What is that? There’s a, there’s a lot of, uh, emerging… I think ambiguity is a perfect word, but confusion is another one.

Mike Gruss: Yeah, and that feels like that’s blurred more in the last couple of years. Yeah.

Susanne Hake: Yeah.

Mike Gruss: Um, Dennis.

Dennis Woodfork: I, I think they covered it. I mean, I, I do think it’s the, the ambiguity of, you know, more, um, actors, more folks in space with their own, um, missions, their own objectives, and how do you tell, right, friendly from foe? Who’s… You know, what is that satellite actually doing? Is it what it said it actually is, right? Those types of things, I think, is a threat. But, um, yeah, I would, I would say the, the ability to shape the perception of, um, folks is going to be a threat, right? The digital nature of space means that if you can make things appear, you know, differently, then I think you can cause unintended consequences, right? And I think that’s a threat. We’re gonna need to make sure when we see things, we know how do we verify what that thing is, um, and then move on to the next thing, right?

Mike Gruss: And do it quickly.

Dennis Woodfork: And do it quickly.

Mike Gruss: Yep.

Dennis Woodfork: Right.

Mike Gruss: All right, let’s talk a little bit about space deterrence, ’cause I think that’s a, a topic that comes up a lot, and I think it’s, it’s also one to me that sometimes can feel very abstract, and it’s hard to, to make sense of. So what does space deterrence look like in five years, and, and how is that even different from five years ago from today? And I’ll open it up to the panel, whoever wants to start.

Susanne Hake: Yeah, I can start.

John Plumb: All right.

Susanne Hake: Um, [chuckles] so, I mean, in terms of how things have changed, right, you know, now, because of all the capabilities that we have in space, we are able to see and understand a lot more of what’s out there, right? Um, and, you know, I think to your specific question in terms of how do you think about space deterrence, maybe an analogous, um, thing to think about is sort of like a neighborhood watch concept, right? Where, you know, I, I don’t have any data in front of me, but I assume that there’s data that says that, um, you know, neighborhoods that have signs that there’s a neighborhood watch or talk about a neighborhood watch have less crime, right? And so maybe there’s a kind of parallel to what’s going on in space of, you know, when there’s an awareness of what’s around you, there’s known capabilities to take images and characterize things. That in and of itself can provide some amount of deterrence.

John Plumb: Yeah, I’ll just, uh, take this in a slightly different direction and say I don’t think deterrence in space is the right framework. I think it’s deterrence. How do you deter conflict? But what you’re really saying is, uh, we now understand collectively that space is a warfighting domain, and things that Dennis and I have worked on is how do we normalize that as a warfighting domain. But that means it’s just one more place where militaries operate, where they try to deter conflict across the entire spectrum. So I think the concern folks have is that in an actual conflict situation, uh, you know, premeditated by design, it may kick off in space, kick off in the cyber domain and space domain, because it feels to the humans on the ground like that may be a little bit less impactful, but it has a huge, uh, impacts on the, on the downstream fight. But I think really, it’s not deterring in space, it’s deterrence. So you have to have credible deterrence across, you know, terrestrial, air, under sea, and space, and be able to operate credibly there, and that’s a difficult thing. It really adds a whole another dimension.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah, I would say, uh, a thousand percent agree with, with both colleagues. Uh, strategic deterrence, I think, for us, is going to look like, uh, establishing norms of behavior and infrastructure that, uh, I think deters bad, bad actors from doing something different. Uh, an example is, um, we’ve got, um, norms of behavior for the sea, uh, and air, and, um, you know, if you see someone doing something unsafe, right, people can point that out and say, “That’s bad,” right? That, that can be a form of deterrence. And I think, uh, for us, the cislunar, the, the domain of space, we’re gonna have the same thing. Establishing, uh, infrastructure and norms will help us deter adversaries. Operationally, I think, um, you look at what General Whiting, the commander of US Space Command, has done, and he’s doing a fantastic job of getting forces ready for conflict, right? For crisis and conflict, and doing that in a way that you can deter our adversaries because they can see, “Oh, they’ve got-… they’ve got it together. They’re actually, not only are they operating and showing proficiency, but now they’re partnering with national, multinational, right, partners in, in commercial, and now they’re showing this inner, you know, locking, uh, network of space power, right? And I think that is operationally an absolute deterrent that needs to continue, right? We need to, I think, accelerate and expand our ability to deter bad behavior, like you said, through all domains. Space is just one lever.

Mike Gruss: Um, I think this year, in particular, since w- the– I’m sorry, since the beginning of 2025, we’re still in a new year, um, we’ve certainly heard more about space capabilities being used more for narcotics, drug interdiction. Um, we’ve heard that from the White House, we’ve heard from the DNI saying it’s a priority, we’ve heard about it from some of the space intelligence agencies. Um, I think that’s a good example, but looking ahead, describe what the role of the Space Force looks like in twenty forty, and how that’s different than from the work that’s being done today. I, I’ll tell you, we had a couple, um, audience suggestions here where people asked about, you know, the inevitable scramble for lunar resources, such as helium-3. That, um, someone asked: Will there be a future military astronaut corps in, in twenty forty that is different from today? So, um, lots of ideas there, but Dennis, do you wanna start?

Dennis Woodfork: Uh, sure, yeah. So I, I think, you know, i- it’s fun to, you know, envision this future, and I, I, I’ve used this analogy before. I think right now, right, the s- the Space Force is like a littoral service, right? If you think about the analogy of the seas, right, you’ve got a brown water navy, uh, and then you’ve got the blue water navy, and those domains are different, right? You think about things differently when you can get out of your boat and touch land, versus when you’re out in the middle of the Pacific and you don’t have the infrastructure and support, right? And I think, so if you think about the Space Force, right now, we are terrestrially tied absolutely, right?

We’re there to establish space superiority in, uh, support of, uh, the national command authorities and what their object- military and national objectives are. But as you look out, right, that changes. The ecosystem of cislunar means you need a blue water navy type space force. It needs to be able to go out, it needs to be able to sustain itself, and it needs to be able to operate in that domain and establish space superiority at the time and place of its choosing, just like we do in the other domains, right? So that means it’s gonna need logistics thought about in different ways, communication, autonomy, AI, all of that is, is different, and it will be different, I think, um, in the twenty forty time.

Mike Gruss: How is that conversation evolving right now? Like, how do you… L- like, where do you s–Because I think that’s a fairly new, at least I’ve– I’m hearing it more frequently now than I was a couple of years ago, but that, “Hey, we can’t… It’s not just this little bit of, of space. It’s, it’s much broader than we have to think about.”

Dennis Woodfork: I, I think folks are starting to think about that. I think, you know, NASA’s commission, um, you know, IM intuitive machines, right, for that inf- cislunar infrastructure, APL’s, um, absolutely a part of that. And I think as people start to think about what does it take to sustain human, uh, presence on the moon, all of those conversations start to expand to, Well, if you need that infrastructure, then you probably need that security. You’ll need that autonomy, so you can make decisions faster. And so I think in, in the corners of people, like commercial companies, as well as labs and industry, I think we are now starting to have those conversations.

Mike Gruss: Susanne.

Susanne Hake: Yeah, um, I mean, you, you started your question asking about, or kind of alluding to the use of space in, you know, Venezuela and some recent drug interdictions, um, and things like that, and I won’t comment on, you know, particular companies and whether or not particular capabilities were used there. But I do think that’s a preview in terms of where we will see space-based ca- capabilities used in the future, right? Moving beyond typical, like, military operations into more disaster relief, into, you know, infrastructure and supply chain, and all these different use cases. So as space is used for so many of these different kind of capabilities in the future, that’s going to require Space Force to kind of evolve how they’re thinking about these things.

Mike Gruss: And what does that look like? Or what– where does that, where does that thinking go? Like, how is that different from today, and where does it go?

Susanne Hake: Yeah, I mean, I think it, you know, requires more integration of capabilities. Um, when we’ve talked about– you know, John talked about deterrence across all of the domains. In order to fully incorporate space, we need that integration of space fully into air, land, and space. So I think that’s gonna be one of the key pieces as space is used for, you know, more use cases, that we have to see that technical integration, that agency, those policy integrations, like, all of those coming together.

Mike Gruss: Great. John.

John Plumb: Yeah, sure. So I think it’s tough to look out fifteen years, right? Five is easier. Uh, I think it’s hard to say what would the different applications be. I think what is clear is the path that we should be on, and people wanna be on, is integrating, uh, Space Force as a military service and a provider of force effects, uh, deeper and deeper into, uh, the war fight, right? And so not… Uh, most of my career, space has been this thing on the other side of a wall, right? You have an exercise, things are happening, and then a little card comes over like, “Oh, this just happened.” Like, “How did that? What do you-

Mike Gruss: [chuckles]

John Plumb: … Here’s a card.” “No, it didn’t,” right? So it’s very- it’s a very confusing way to run exercises, but I think as, uh, we integrate space more and more… And that’s the thing that I think is strange, because if you think about the challenge of fighting in space and our overdependence in space on the nation, which is sort of an Achilles heel, but also our strength, uh, one direction would be to get-… away from being connected to space. I just don’t see it. I don’t think it’s happening. I think it’s being more and more connected, and as we throw thousands and thousands more satellites up, the connectivity is gonna increase in a way that is almost counterintuitive. Uh, and I think, uh, a f- a really, uh, uh, lean, mean, fighting machine of a space force in twenty forty is gonna have to account for this massive amount, really, of metal in space, doing all of these services, and how do you use that to the advantage of, of the joint force? It’s, uh… I think it will- it, it looks like baby steps now. I think fifteen years gets- puts us on the right path.

Mike Gruss: All right, here’s the AI question, and we’ll keep this as a-

John Plumb: Do you have a quantum? Do you have a quantum question, too? [laughing]

Mike Gruss: No quantum. Then we’ll save that for the next one. Um, what’s one surprising role AI will play in space operations? And we’ll keep this as a lightning round, but Susanne, you can start, since I know you’re excited.

Susanne Hake: I know, I, I set myself up for that, huh? Um, so, you know, I think, and this is, like, kind of with–especially with a Vantor perspective, is using AI to really, you know, look at imagery, right? Um, there’s so many images that are taken of Earth or of space right now, and being able to use AI, run algorithms, you know, identify and characterize what’s in those images.

Mike Gruss: And again, that’s faster than w- faster than we’ve ever been able to do that.

Susanne Hake: Yeah, faster than we’ve been able to do it before, and more accurate as well.

Mike Gruss: Okay, John.

John Plumb: Yeah, so I, uh, going farther on that, I would just say, uh, tremendous amount of satellites in space doing imagery, doing different types of sensing, and h- tons of data. How do you process that data? Right now, the way a lot of the data is processed, it all gets piped back down to Earth and is processed on Earth. So I think, uh, the natural evolution here is true edge processing, uh, where a satellite itself or a small group of satellites communicating can solve what is needed on the ground by the human operator, filter out the rest to reduce how much flow, you know, how much data flow has to get to a war fighter or get to a center, and I think that’s a really interesting, uh, thing that’s just right, it’s tantalizingly close to a thing that we should be, we should be getting after.

Mike Gruss: And we’re, we’re starting to see some companies really look at that, I think.

John Plumb: That’s right.

Mike Gruss: Dennis.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah, as, uh, it, it, it’s actually a, I think, a two-sided coin with AI for me. So I, I think AI is going to, and, you know, if we pr- project out to twenty forty, I think AI is gonna be key in saving, uh, a life. I think as we have humans and astronauts and things like that, making decisions, medical decisions, whatever it is, AI will be potentially the thing that actually w- we’re leaning on to, you know, make recommendations on how to save someone that is out there so far that they can’t get back fast. On the other side of that coin is, I think AI is gonna enable us to close kill chains, so destroy things, uh, faster than ever, right? Uh, AI is about decision superiority, right? And so making decisions in that OODA loop faster than your enemy is what I think is key. So both destroy and save, I think AI has that promise of.

Susanne Hake: I was just gonna add one thing, I think, to build on that as well. You know, it’s really, you know, who can use AI the best? Who knows when to use AI? Who knows when not to? When you think about, in particular, using AI in more of a, you know, like, military or kinetic or kind of war context, there’s real decisions to be made that are not just looking at AI and making a decision, right? There’s strategic, there’s moral, there’s all these aspects to it. And so when you think about the use of AI, it’s not only, like, who has the best models, but it’s also when do I apply it and when don’t I apply it, right?

Dennis Woodfork: Right. Yeah, absolutely.

Mike Gruss: That’s a good question, when not to use AI.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah.

Mike Gruss: Um-

Dennis Woodfork: On your homework.

Mike Gruss: Yeah. [laughing]

Thanks. Um Let’s talk a little bit about, uh, culture and talent, because I think that’s something that comes up a lot when we’re chatting about the Space Force, and the Space Force be- being a new service, I think they, they still have that opportunity to shape their culture and talent. And so how, how does that culture need to evolve to retain talent required for this very fast-moving environment? We all– we’ve just spent the last thirty-five minutes talking about in this very highly technical domain, and Dennis, I know this is something you’re passionate about, so let’s start there.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah, absolutely. Uh, thank you. So we, I think, uh, so I don’t think there’s anything, like, I would say that needs to evolve because there’s something lacking. I, I think, um, you know, the Space Force has done an absolute fantastic job creating, uh, war fighters that have a technical mindset, like, how do my- how does my technical job support the joint fight? And I think they’ve done a fantastic job of building that war fighter culture. Um, I– what we want to see more of is this permeable membrane where the guardians are actually interacting with industry and understanding how their technologies can enable, right, their mission set, there’s that space superiority. Um, so, you know, we’re, JHU is the, the PME, the Professional Military Education, uh, for the Space Force, and we treasure that at APL because we’re part of that, where we can bring guardians, right, that are getting their education to APL, and they can learn about some of the technologies. How do we do kill chain engineering? How do we do, you know, communications PNT? All of that is, I think, helping build this culture of a technically oriented war fighter that really can outthink and out-innovate our, our adversaries, so I think it’s really important that they continue that.

Mike Gruss: John.

John Plumb: Yeah, uh, Dennis, I think you’re, uh, exactly right, and I… So I was a submarine officer, right? So the Navy, uh, is also– I, I wish the Space Force had taken the Navy ranks, whatever. Um, but the reason I bring up the submarine piece is I was a engineer, a nuclear engineer, and a war fighter, and I think this is the culture that the Space Force needs to push. And this is, you know, I, I, I would disagree to say we’re right there. I mean, I think this is a, this is a generational problem. This is gonna take fifteen years to push this kind of culture through, and you’re gonna need to find a way to have continuity across different chiefs of service, different secretaries of the Air Force. Uh, but I think, uh, engineers first-… that can understand satellite mechanics and operations, and as well as SATCOM and, and moving, you know, mo- moving data around, and then the idea of, like, acquisition and operation. I think I’m personally, uh, not convinced that those should be two separate paths. I don’t understand why they are not more intertwined, and I think that would make the Space Force stronger. I think it would make the conversations back with industry stronger, and I think it would naturally drive, uh, the cadre of, of Space Force professionals to be more and more engineering-inclined to be able to, to survive that academic level. So I think that is the place to go. It’s probably the most acquisition-heavy of any service, and in a way where it’s absolutely important, and it actually moves at a faster clip than acquisition in other services, uh, which is a shocking thing to say. Um, so to me, there’s a–there is a future there, but it, it really difficult, as with anything with the military or as with anything in the Pentagon, really difficult to kind of keep the movie going year after year, uh, with changes in leadership, and not even just political, just changes in leadership, and so people wanna put their new things. So I think some vision of where that should go would be really helpful.

Susanne Hake: Um, I think from a kind of talent and recruiting perspective, right? Um, I mean, we live in a world where the best engineers are paid, like, pro football salaries to go to some of the top companies in the military, and many of us just simply cannot compete with that. Um, but, you know, I think from a talent perspective, leaning more into kind of the mission side to hire those engineers, that, that’s something that Space Force and, you know, any of the, the military can provide that almost no company can, right? Proximity to the mission and impact. So I think when you’re competing for talent, and money isn’t going to be the way that you’re bringing talent in, kind of leaning into some of those other aspects.

Mike Gruss: We have about two minutes left, and we did time this pretty well. I have one more question here. Um, but it’s the space policy question, which means we have to l- leave some time for John here. But what’s one policy decision that could be settled in, let’s say, the next three years that would set the Space Force up for success in twenty forty, which is what we’re talking about tonight,

so-

Dennis Woodfork: Do you want to, do you want to-

John Plumb: You want me to start?

Mike Gruss: No, let, let’s, we’ll, we’ll let him.

Susanne Hake: Great.

Mike Gruss: Let’s let him close.

John Plumb: All right. Ticktock. Ticktock, Dennis.

Dennis Woodfork: All right. Okay.

Mike Gruss: All right, Dennis, go ahead.

Dennis Woodfork: Yeah, so really quickly, I think, uh, our ability, and it’s kind of probably what, uh, branching off of what he’s gonna say, is our ability to partner with our allies, um, in a way that allows us to really be lethal in what we’re doing for, for space warfighting. Uh, I, I think being able to share data is one thing, but being able to be interoperable in our technologies and what we’re doing, um, on orbit and on the ground is something that we just– we need to accelerate our ability to integrate with our allies so that we can, um, show that united front to our adversaries.

Susanne Hake: Yeah, actually, I was– I had a similar thought. It’s really about kind of that interoperability, whether it’s with other countries and allied nations or setting kind of technology interoperability and integration. Um, if we don’t have that, we’re not going to be able to bring in new technology and capabilities. Um, so yeah, I think it’s really about that, and we’ve left you a little bit of time.

John Plumb: Great, 48 seconds. [chuckles]

Mike Gruss: Um, take us home. [chuckles]

John Plumb: Yeah. So look, I’m gonna end where we started, at least my opening comment, which is, I think the fundamental, uh, hurdle to, uh, moving faster, doing interoperability with allies or even across, [chuckles] uh, different services, is the classification, overclassification problem. Space remains overclassified. Uh, senior-level leader, le- senior-level leadership pushes down to try to get that solved, and it still is not moving fast enough. It takes too long to get your clearances, uh, on the industry side. It takes too long to get a SCIF set up. It– And that isn’t even getting to the point of why are these things still so classified that it’s hard to move the data around? And I think three years is the perfect timeframe. It would bring it right to the end, end of this administration. I really think they could solve this problem.

Mike Gruss: Great. Thank you. Let’s have a big round of applause for our panel. [audience applauding] [upbeat music]

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

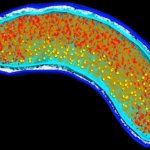

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

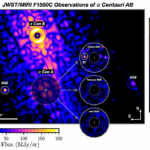

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits