Now Reading: ‘As far as I know, I’m still the assistant administrator of NESDIS.’

-

01

‘As far as I know, I’m still the assistant administrator of NESDIS.’

‘As far as I know, I’m still the assistant administrator of NESDIS.’

In 2025, more than 322,000 civil servants left jobs voluntarily or were dismissed out of a workforce of roughly 2.4 million. The 13% drop in staffing is the largest single-year decline since the end of World War II. In total, more than 5,000 people who were part of the federal space workforce left their positions. Senior executives with decades of experience retired alongside younger staffers whose posts were eliminated or who sought opportunities in the private sector or academia. This is one of eight conversations with some of the remarkable people who recently left the federal workforce.

Stephen Volz

Current position: NOAA Satellite and Information Systems Assistant Administrator (on administrative leave).

With a newly minted PhD, Stephen Volz was eager to work at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in 1986. He was assigned to NASA’s Cosmic Background Explorer, a space telescope to investigate the origin of the universe. He later oversaw a Space Shuttle experiment, before moving to Boulder, Colorado, to develop cryogenic cooling systems at Ball Aerospace for NASA’s the Space Infrared Telescope Facility, later renamed Spitzer Space Telescope.

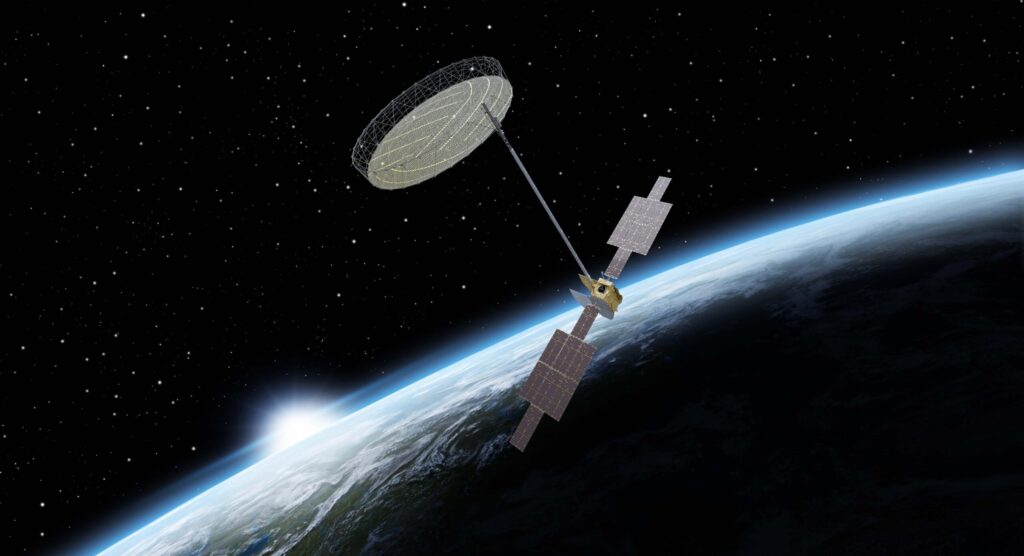

After more than 15 years concentrating on space physics, Volz returned to Washington in 2002 to lead a series of NASA Earth Science missions including the Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite. He managed 14 NASA Earth Science flight missions and cleared the way for more, before moving to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2014. Over the last decade, Volz has overseen NOAA’s constellations in low Earth and geostationary orbit and deep space that inform terrestrial and space-weather models.

Why did you decide to work for NASA in the first place?

I studied low temperature liquid helium. I liked the science of quantum mechanics and quantum physics. It was intellectually challenging for me. Also, I’m a child of the space age. I even applied to be an astronaut in my mid 20s. When I saw a NASA Goddard position, I jumped on it. It looked exciting.

Was it exciting?

It was. Cosmic Background Explorer was ramping up at Goddard and it had a liquid helium cryostat for cooling the instruments. They needed somebody to take over that piece of it. Talk about a crash course in big programs and big science. From then, it was one interesting and challenging job after another. I worked on a liquid helium experiment on the Space Shuttle. I worked on a liquid helium cryostat for the Space Infrared Telescope Facility at Ball Aerospace.

After that, I came back to the D.C.-area to work in Earth Science. It was a big change. I was no longer the manager of a program. I was the manager of managers. That brought me over eventually to NESDIS [the National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service].

What are some highlights of your career?

At NESDIS, I got to lead the biggest integrated civil Earth-observing system in the world. We got the weather satellites off the Government Accountability Office’s list of high-risk programs. We created a sustainable space weather observing capacity for the nation, which we didn’t have. We defined the next generation of geostationary satellites with [Geostationary Extended Observations] GeoXO, which is now under challenge in terms of its construction.

Learning to lead NESDIS has been one of the most rewarding activities of my career. It’s been a great run, working with the public sector, private industry, international and seeing everybody work together for common objectives.

What challenges did you face?

I’ve always done well in science and tests and in my work. In school, I was often the smartest guy in the room. At NASA, it’s not that way. There’s a lot of intellectual competition. Figuring out how to build teams and work together took some time.

Cultural change was another challenge. The cultures of NASA and NOAA are very powerful. The challenge is getting people to recognize the need for change without invalidating the history they brought to the table. I can’t say I’ve done that perfectly. But I’ve certainly learned a lot about how to celebrate the history, but not let that history prevent evolution.

You also are ushering in a new generation of weather satellites.

We have to deliver weather data without interruption for a long time because people rely on it. How do you inject new ideas and new methodologies into that environment? Creating a different architecture for a new generation of satellites in geostationary orbit. Or for low Earth orbit, breaking up a big satellite with a bunch of instruments into a bunch of little ones. It looks simple as an architectural study, but the implementation ripples through the data systems.

On the budget side, convincing the stakeholders was another challenge. For GeoXO, it took us six years to get Congress, the public, the National Weather Service and the administrations to agree. The new administration came in with a different approach, not recognizing any of the previous work as having value. How do we deal with that? We’d love to have a conversation.

Why is your work important?

Early on it was exploration. The NASA approach, which is question-driven, is responsive to the curiosity of people who want to understand how the universe works. On the Earth-science side, it’s much more palpable. We face the challenge of the millennium. How do we live well in a changing world? Our work provides information that people need to make good decisions. NOAA’s Earth observers and data and information systems have never been more important. We are no longer just the observer of the world; we’ve become the actors.

Are you referring to greenhouse – gas emissions?

It’s the greenhouse gas emissions and the climate change that comes from that, but also pollution and biodiversity loss. Observing all three helps us see the feedback loops and connections.

What were you working on before you were placed on administrative leave?

To see the first space weather mission launched to Lagrange point one. To see continued development of GeoXO and to see the development of the next generation of low Earth orbit systems. At the same time, to bring NOAA data together in a cloud-based common framework with the intention of making it all interoperable.

Those plans have been disrupted significantly because of the reorganization of the federal government by this administration. I’m not saying everything they’re doing is bad. We’ve learned a lot about how we could more effectively apply the resources we have, but it has certainly disrupted progress. The Space Weather Follow-On launched in September, but the construct of the low Earth and geostationary orbit constellations are up in the air.

I’m no longer leading NESDIS, which is sad for me because I liked that job, and I did well in it. I’m still fully committed to Earth observations and the integration of all the data and information. I still am an active and interested participant in bringing together different parties to collect and integrate Earth observations to get information out to people who need it. We succeed only if our partners succeed, across agencies, across governments, industry and public domain as well.

What were the circumstances of your departure?

I’m very confident that all the actions I’ve taken are for the good of the country and the best interests of NOAA. I have no insight into what led the [Commerce] Department and NOAA to place me on administrative lead. No one at NOAA or the Department of Commerce has reached out to share with me the results of their investigation. I await their conclusions. As far as I know, I’m still the assistant administrator of NESDIS.

Is there anything else you want to say?

In my 30-plus years in aerospace, I’ve been privileged to work with dedicated experts and creative geniuses in the federal agencies across NOAA, NASA, USGS, the Air Force, FEMA and others. I have worked side by side with international experts from almost every continent. I’ve worked with the private sector and academia, with dedicated scientists and engineers here and abroad.

We’ve created an incredibly cross-agency, multinational integrated observing and information system that provides Americans and people around the world with accurate and precise information every day. I’m distressed to see that challenged as overbuilt and underutilized. This system is robust, resilient and reliable. It needs improvement. Resources are tight and we often are too focused on hardware improvement and not end-user outcomes. We can do that better. But I believe the information and services providers are too vital to be tossed aside with the premise of a better deal or a cheaper system that can make one player profitable. That’s the wrong approach to deal with a system that is essential and well-performing right now. It should be improved but should not be discarded.

An abridged version of this interview first appeared in the February 2026 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

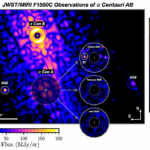

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits