Now Reading: If the Winter Olympics went interplanetary, where else could you ski in the solar system?

-

01

If the Winter Olympics went interplanetary, where else could you ski in the solar system?

If the Winter Olympics went interplanetary, where else could you ski in the solar system?

Every winter, skiers chase smooth carving turns, reliable snow and that dream run. As the Milano Cortina Winter Olympics 2026 unfold on Earth, it raises a fun question: if the Games ever leave our planet, where else in the solar system could you actually ski?

Skiing is surprisingly picky about physics. Snow, gravity and temperature all have to cooperate for conditions to be suitable, and very few worlds get that balance right.

Earth: the gold standard

Earth doesn’t just have snow; it has historically reliable snow. Our planet’s axial tilt of 23.5 degrees produces regular seasons, allowing winter temperatures to build and maintain good snow conditions across mountain regions.

But skiing depends on more than just snowfall.

On Earth, skis can glide across snowy surfaces because of the way water ice behaves. Ice surfaces develop a thin, mobile surface layer, sometimes called a quasi-liquid or premelted layer, that reduces friction and enables sliding. Earth’s gravity, at 1g, provides us with enough downward force for skis to grip and carve.

Put all those factors together — seasonal snowfall, water-ice physics and moderate gravity — and Earth produces something rare in the solar system: ideal skiing conditions.

Moon: dust, no snow

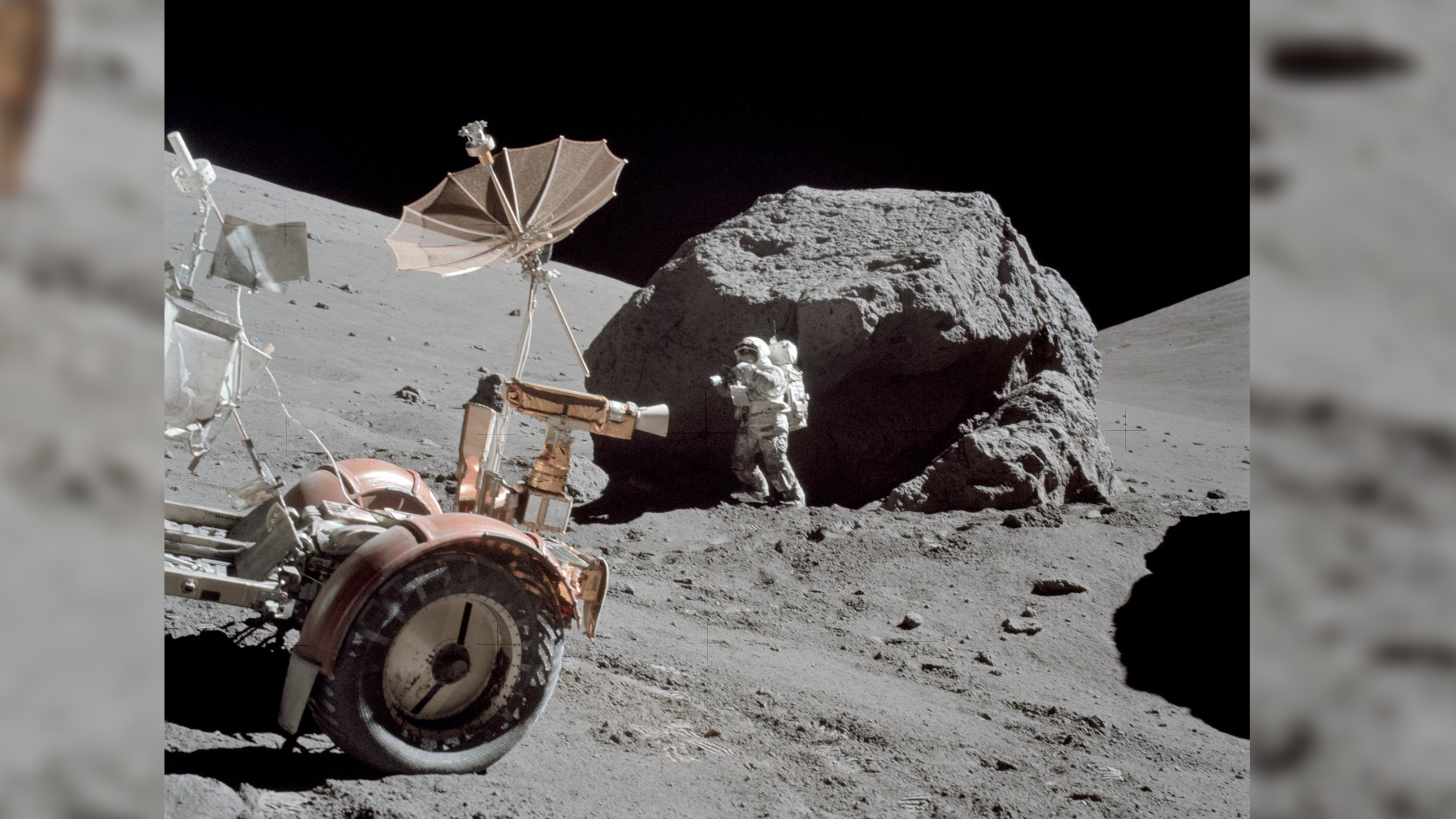

The moon may be our closest companion and the easiest destination to head to for a cosmic holiday, but would you want to pack your skis?

The moon has no atmosphere capable of supporting weather or snowfall and its surface is covered in regolith — fine jagged sharp rock material, far from optimal skiing conditions.

However, that didn’t stop former NASA astronaut and geologist Harrison Schmitt, part of the Apollo 17 crew, from giving it a go in 1972. Schmitt claimed his knowledge of cross-country skiing helped him glide effortlessly across the dusty lunar surface.

“When you’re cross-country skiing, once you get a rhythm going, you propel yourself with a toe push as you slide along the snow,” explained Dr Schmitt, according to the BBC.

“On the moon, in the main you don’t slide, you glide above the surface. But again, you use the same kind of rhythm, with a toe push.”

Schmitt also commented that the mountainous eastern rim of the Sea of Serenity, the Apollo 17 landing side, would make an ideal alpine skiing spot, according to the BBC.

“I think there are some excellent downhill skiing areas there.”

So perhaps the moon could make for a decent ski holiday afterall, take it from the man who’s been there, done that.

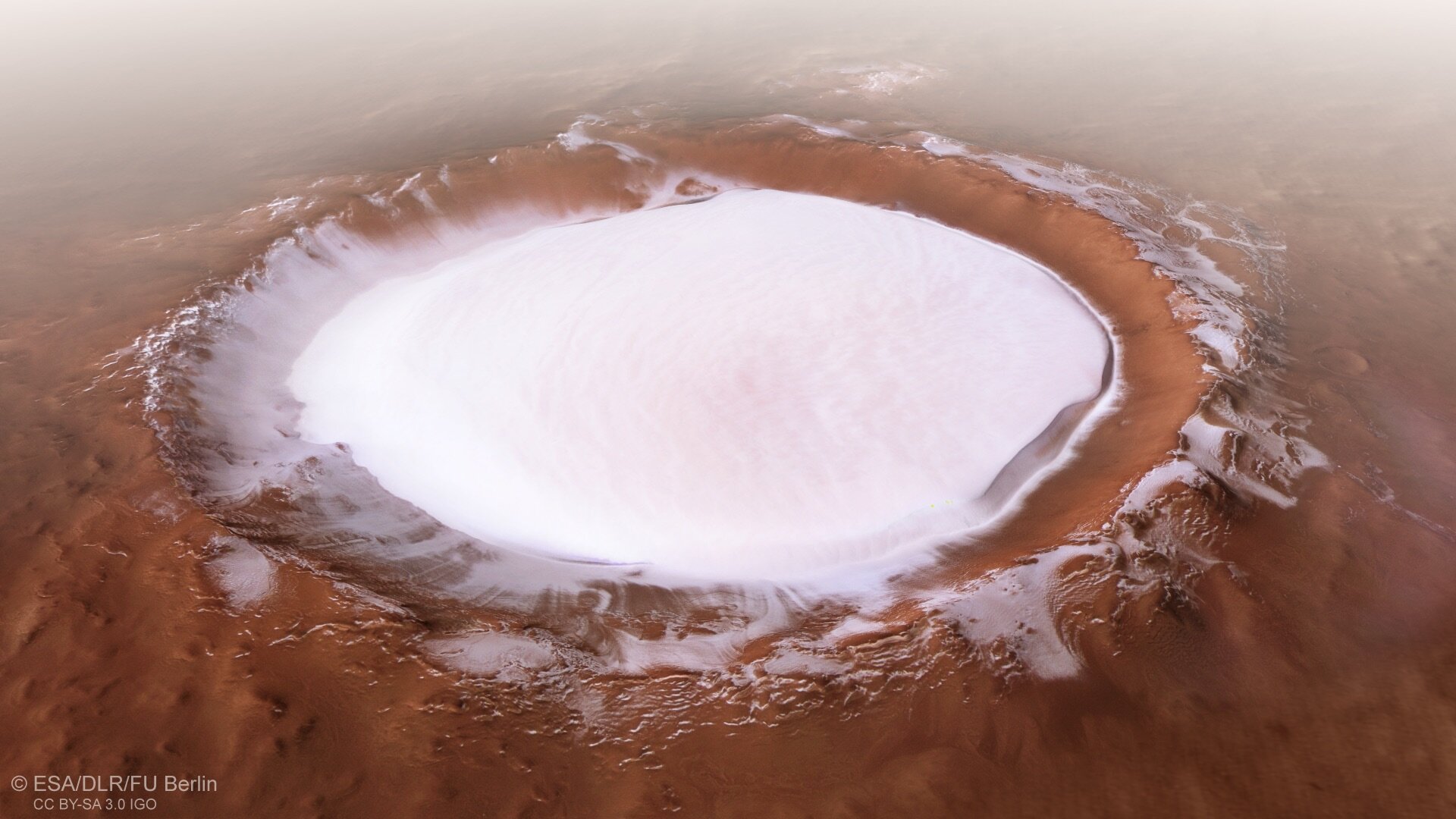

Mars: Looks promising, skis terribly

At first glance, Mars looks promising. It has seasons, polar caps, steep slopes and even snowfall. Sounds good so far, right?

Wrong. Much of Mars’ winter snow is not water ice; it’s frozen carbon dioxide, also known as dry ice. Under Martian atmospheric pressures, 6 to 10 millibars or about 1/100th that of Earth’s, CO2 doesn’t melt into a liquid. Instead, it sublimates directly from a solid to a gas.

That matters for skiing.

When pressure is applied to skis on dry ice, the mechanical stress would fracture the brittle, dry surface. Instead of forming the lubricating melt layer like water ice does on Earth, the material would sublimate, destabilizing the surface below the skis.

So if you’re into chaotic sliding rather than carving, then go ahead, Mars is for you.

Europa: Ice everywhere

Europa, one of Jupiter‘s moons, is covered in water ice, the right material — in theory. Afterall, water ice is exactly what skiing on Earth depends on. But Europa’s environment throws a wrench in the works.

Surface temperatures average around -260 degrees Fahrenheit (-160 degrees Celsius). At those temperatures, ice becomes extremely rigid. At such extreme temperatures, the mobile surface behavior that helps skis glide on Earth would be greatly reduced. In Europa’s near-vacuum, heat from friction would dissipate quickly rather than building a lubricating surface layer. Combine that with the gravity that’s only about 13% that of Earth’s and skis would press so lightly on the ultra-hard surface that instead of carving into responsive snow or ice, you’d likely just scrape and drift across something closer to frozen glass, with little control.

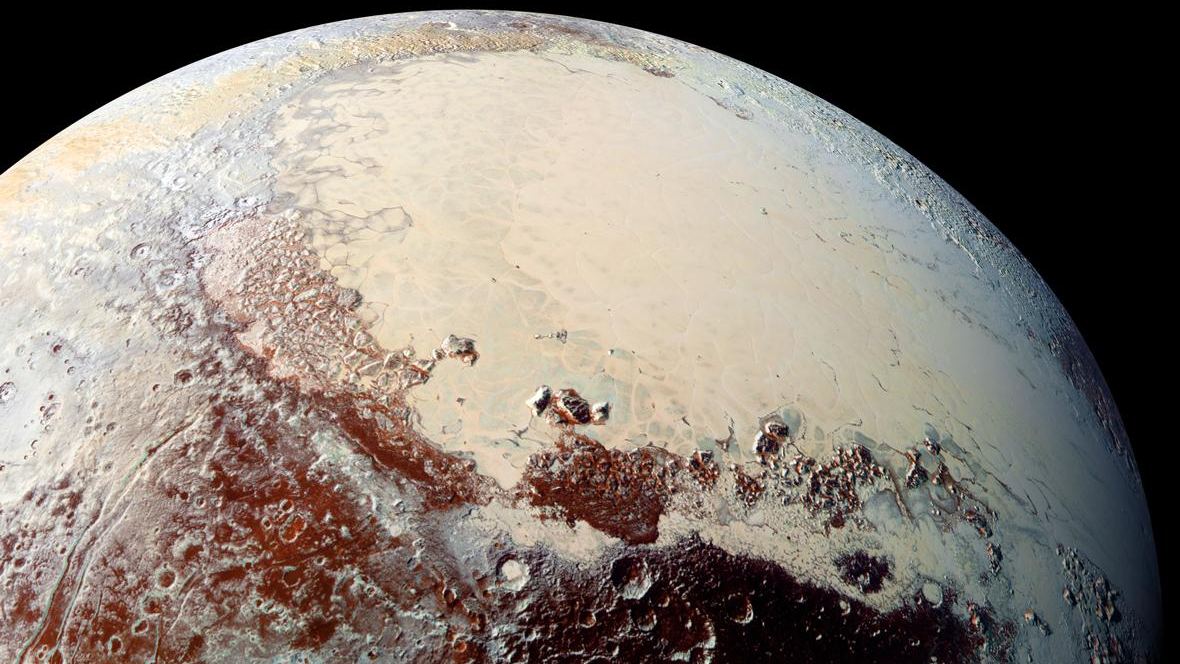

Pluto: exotic but impractical

Pluto is coated in nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide ice, and may be the strangest solar system ski destination of all.

The rocky world’s average temperature is about -387 degrees Fahrenheit (-232 degrees C). In such frigid conditions, Pluto‘s ice behaves (yes, you guessed it) very differently from water ice on Earth.

Skiing on nitrogen or methane ice would feel rigid and brittle, and make for an unpleasant experience. While carbon monoxide ice is highly volatile, in Pluto’s extreme temperatures, it would remain solid and glass-like.

None of these would form the loose, granular snow conditions that compress under skis on Earth and Pluto’s gravity only makes things worse. At about 6% that of Earth’s, Pluto’s gravity also means that you’d not be able to apply much downward force and skis would only press very lightly on the surface. Without the edge grip you can get in Earth’s snow, carving controlled turns would be extremely difficult, so you’d end up with more drifting than skiing.

The final verdict

Across the solar system, there are plenty of worlds that have ice, snow and even impressive slopes, but only one has the three working together that allows for enjoyable skiing.

If the Winter Olympics ever do go interplanetary, Earth would still take gold.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

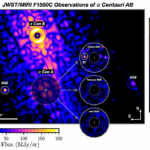

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits