Now Reading: Dale Andersen’s Astrobiology Antarctic Status Report: 15 February 2026: Diving Under The Ice At Lake Untersee

-

01

Dale Andersen’s Astrobiology Antarctic Status Report: 15 February 2026: Diving Under The Ice At Lake Untersee

Dale Andersen’s Astrobiology Antarctic Status Report: 15 February 2026: Diving Under The Ice At Lake Untersee

Birgit Sattler assists Dale Andersen as he begins a diver underneath the ice cover of Lake Untersee, Antarctica — credit: Klemens Weisleitner

Keith, Sorry for the quiet—our days have been packed, and out here every usable hour feels borrowed. Since my last report the weather has changed its mind a few times. The snowstorm I mentioned in my last note covered the lake with a few inches of snow for about a week, with steady drifting around our camp. It slowed us down, but did not stop us and we still managed plenty of work in the margins between squalls.

A few days have been outright gusty—50 mph or more—never ideal when you are trying to handle gear with cold hands, and definitely noisy when you are trying to sleep. The bright side is that we have not been hit by anything truly serious (100+ mph winds like we’ve experienced in previous seasons), so by Untersee standards we have been lucky. Most of the snow on the lake has now blown clear and we hare back to hard ice.

View at Lake Untersee Base Camp on 15 February 2026 showing the prevailing antarctic winds. Copyright Dale T. Andersen

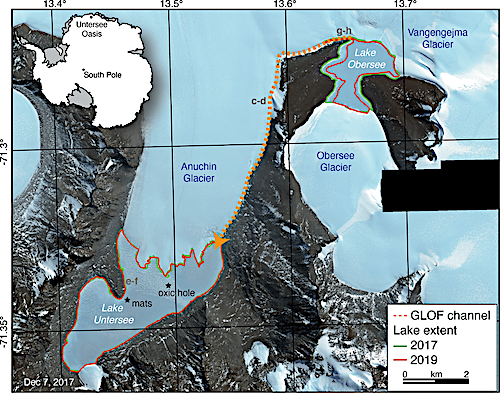

Glacial lake outburst floods enhance benthic microbial productivity in perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee (East Antarctica), October 2021, Communications Earth & Environment 2(211)

Not long after the snowy stretch, four of us traversed up the Anuchin Glacier to Lake Obersee with three main goals. Denis and Efe climbed to the higher (~1000 m contour), snow-free elevations to collect ground-ice samples. Klemens and I worked at Obersee’s shoreline to repair a small climate station near our 2013 camp—the anemometer prop failed a few months ago, so we swapped it for a new one. We also collected additional samples of cyanobacterial mats now exposed at the surface.

Those mats once lived and thrived underwater beneath the ice cover of Lake Obersee. After the glacial outburst flood at the end of 2019 into early 2020, the lake released a huge volume of water, dropping the lake level by more than 11 meters. The ~4 m ice cover buckled along the steep shore. Mats that once hugged the lake margin were trapped beneath that ice for years, then gradually re-emerged as the ice ablated via sublimation/evaporation over the last two seasons, revealing former lake bottom and the mats themselves—now exposed to cold, dry air, bright sunlight, and elevated UV.

It is a rare natural experiment: we can watch these communities dry out and pass from active benthic mats into the sedimentary record—while a small fraction of cells may be carried by the wind to seed new habitats, from cryoconite on the glacier to nearby ponds. It matters for Antarctica because we are trying to understand how organisms disperse and survive across the continent; it also sharpens how we think about biosignatures—and their preservation—in ancient lakebeds on Earth and on Mars.

Paper citation and link: Faucher, B., Lacelle, D., Marsh, N.B., Jasperse, L., Clark, I.D., & Andersen, D.T. (2021). Glacial lake outburst floods enhance benthic microbial productivity in perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee (East Antarctica). Communications Earth & Environment, 2, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00280-x Open Source Link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-021-00280-x

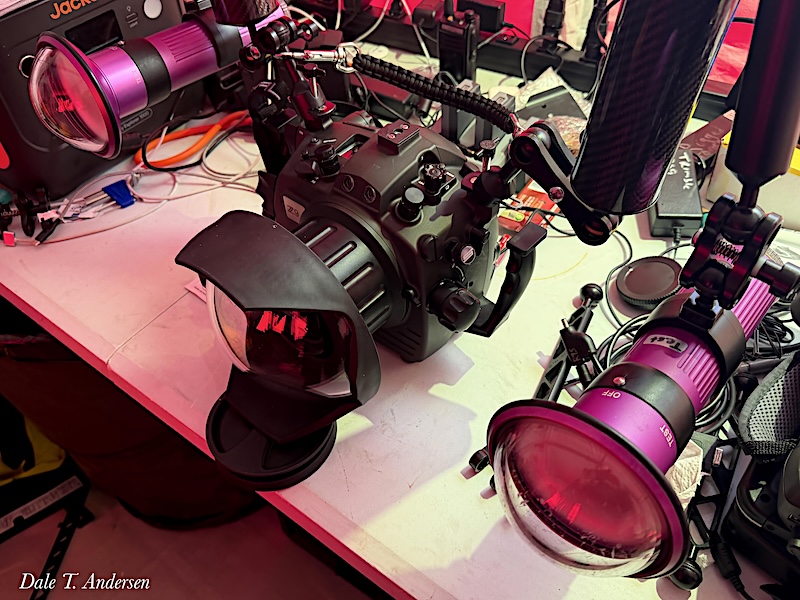

Documenting our work—and especially the environments we study—has always mattered to me. Whenever conditions allow, I bring a camera beneath the perennial ice to record the microbial ecosystems of these lakes, and Lake Untersee in particular. Very few people will ever see this underwater landscape in person: the dim water, the sculpted mats, the textures that quietly tell a long story. So I try to share it as faithfully as I can—both to spark curiosity in students and the public, and to capture fine-scale details that are genuinely useful for science. Today’s setup: a Nikon Z9 with a 14–24 mm in a Subal housing, paired with Keldan lights to bring back the color and structure that the ice and water otherwise keep hidden. – Dale T. Andersen

The hole melter (the modified Hotsy steam cleaner) heats the water/glycol mixture that circulates through the closed loop, including the stainless-steel coil. The fluid cools as it gives up heat underwater, then returns to the heater to be brought back up to temperature before making another pass through the loop. We developed this basic method in 1978, when we first began studying microbial communities on the lake bottoms of the McMurdo Dry Valleys. – Dale T. Andersen

Hole melting begins when we lower a ~1.5 m stainless-steel coil into the pilot hole, with its lower end extending just beneath the underside of the ice. The coil connects to a hot-water generator (a Hotsy steam cleaner) that we modified to circulate a boiling-temperature water/glycol mixture through a fully closed loop. As the coil heats, it warms the surrounding water; that heat convects upward along the hole walls, gradually widening the opening. Once the hole reaches the diameter we need—for example, large enough for a diver—we pull the coil and shut the system down. – Dale T. Andersen

Back at Lake Untersee, we finished melting the dive hole. With the team’s help I was able to get beneath the ice to collect sediment cores and microbial mat samples from the thin, photosynthetic veneer that carpets the lake bottom. Dropping through meters of ice into that dim water still feels like stepping back in time.

Research Team members (dive tenders) assist Dale as he prepares to begin his dive under the ice cover at Lake Untersee. — credit: Klemens Weisleitner

As you move closer to the bottom of the lake, you can almost imagine Earth’s early biosphere nearly 3.5 billion years ago – colonial collections of microorganisms carrying out the heavy lifting of planetary change, reshaping the atmosphere and oceans toward what we recognize today. The textures and fabrics on Untersee’s floor echo patterns we recognize from the deep rock record. It is humbling to see how little some fundamental strategies have changed: colonize a surface, harvest light, stabilize your immediate setting, recycle chemistry, grow, adapt, persist.

Beneath Untersee’s ice, the blue water column opens into a gentle landscape of microbial mats—soft contours, fine textures—and then, rising from it all, the large conical stromatolites. With the illumination from my lights, the scene feels almost impossible: a living “seafloor” beneath a roof of ice, quiet and beautiful, shaped by microbes doing what they have done for ages. It’s like a postcard from the past—an echo of early Earth—except that worlds like this are now rare, tucked into a few hidden refugia, and here their ancient cousins—so many generations later—are still building. — Dale T. Andersen

The samples I returned to the surface will help us refine the biogeochemical story of Lake Untersee and the structure and function of its microbial community – who is there, what they are doing, and how they manage it so effectively in a place most life would find unlivable. They will find their way into laboratories at the University of Ottawa, University of Innsbruck, Georgetown University and elsewhere.

Denis and Efe also spent a considerable amount of time on the side (literally) of the Anuchin Glacier collecting ice samples for radiocarbon dating and other isotopes (DHO), and collecting water samples from local ponds found within the marginal moraine on the western side of the glacier.

Drilling the initial dive hole — Dale T. Andersen

Alex and Birgit have kept very busy pushing on the environmental DNA work, including filtering large volumes of air through specialized filters for later sequencing. We are trying to identify which cells ride the wind across this landscape, and where the limits of gene dispersal and organism viability might sit in a vast polar desert.

Lake Untersee is an oasis in that desert—nesting snow petrels and skuas, lichens, a few mosses, and the life hidden beneath the perennial ice covers of Untersee and Obersee … plus the occasional scientist. It will be interesting to see whether the air samples pick up signatures of that wider ecosystem (including, perhaps, us)—and even traces of windborne cells lifted from Obersee’s newly exposed, drying mats.

Last week we also completed a 3.5 km transect across the Anuchin Glacier to collect additional stable isotope data (D, H, O) for comparison with earlier datasets, and to address new questions about ice loss through ablation (sublimation/evaporation) over time.

We will also gather more high-resolution GNSS data using the Trimble R9s base station and R12i rover. Tracking lake level, ice-surface elevation, and a few selected boulders will let us quantify subtle changes year to year, including how far those boulders migrate across the ice.

Yesterday we started winding down the science phase and shifting time toward breaking camp. We are packing gear we no longer need and taking down tents that have finished their job—lab tent, small garage/work tent, dive tent, and a few personal tents. Over the next few days we will “shrink” the camp so we are ready to return to the Ultima Antarctic Airbase on the 19th.

On the 18th, Ultima will send tracked vehicles with a large sled to haul the bulk of camp supplies, research equipment, and remaining food; the team will follow as we came in, by snowmobile. The forecast looks fairly favorable, which should help as we close out the season’s last logistics.

Once back at the airbase, we will spend several days sorting and repacking. Some equipment will stay here in Antarctica for overwinter storage—ready for our next field season (now scheduled for Oct–Dec 2026). A smaller set will head home with us: polar clothing, personal items, and samples, to be shipped once the logistics chain is in place.

I hit 70 just before heading south this field season – hard to believe that, in some ways, my job description has barely changed since my first dive beneath Antarctic lake ice at 22 in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Yep, gotta love what you do in life!

I will post a note before we depart and hope to set up tracking so you can follow along as we make the trip back from Untersee to the Ultima Airbase facility.

Cheers from the shores of Lake Untersee

-Dale-

Keith’s note: Astrobiologist Dale Andersen is heading back in Antarctica at Lake Untersee in January-February 2026 for another field season of research.

2025/26 Lake Untersee Antarctic Field Season Team Members

- Dale Andersen, Ph.D. Carl Sagan Center, SETI Institute, Mountain View, CA

- Birgit Sattler, Ph.D. University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

- Allessandro Cuzzeri, Graduate Student (Ph.D. candidate) University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

- Denis Lacelle, Ph.D. University of Ottawa, Canada

- Efe Kemal Koc, Graduate Student (M.Sc.) University of Ottawa, Canada

Dale and I have been proving research updates – from Antarctica – since 1996. We think we actually had the first webserver (located in my old condo) updated from Antarctica. More details here: Dale Andersen’s 1996 Antarctic Field Research Photo Albums

Astrobiology

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

07Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)