Now Reading: Scientists may have found a ‘missing-link’ black hole ripping up and devouring a star

-

01

Scientists may have found a ‘missing-link’ black hole ripping up and devouring a star

Scientists may have found a ‘missing-link’ black hole ripping up and devouring a star

Astronomers have discovered that an unusual optical flare is the result of a star being ripped apart and devoured by a black hole — and what really sets this so-called Tidal Disruption Event (TDE) apart is the fact that the black hole involved seems to be an example of an elusive “intermediate mass black hole,” a class of this object that has challenged astronomers for decades.

TDEs generally occur when stars venture too close to the supermassive black holes that sit at the heart of large galaxies, resulting in the immense gravity of these cosmic titans simultaneously squashing the stellar body horizontally while stretching it vertically. This “spaghettification” creates a stellar noodle wrapping around the black hole. Some of the remains are fed to the central black hole, while much of it is blasted away at near-light speeds as high-energy jets. These events can take hundreds of days or even years to fade.

“AT2022zod has the characteristics of a TDE, a flare we observe when a star is ripped apart by interacting with a black hole. These events are, in general, not common, but since we expect a supermassive black hole in the center of almost every galaxy, TDEs are expected to be observed in the center of their host galaxy,” team leader Kristen Dage of Curtin University, Australia, told Space.com. “However, AT2022zod is slightly off-nuclear, and very short in comparison with previously observed TDEs, while still highly energetic.”

When observed at distances as great as this, TDEs generally last for hundreds of days, making AT2022zod’s month-long duration from Oct. 13 to Nov. 18 highly unusual. “The combination of being hosted by an elliptical galaxy, famously home to large populations of star clusters, while being off-nuclear and of short duration, made us intrigued that this may be one of the elusive intermediate mass black holes that might exist outside the center of the galaxy, and more importantly, open a new avenue to search for and study them,” Dage continued.

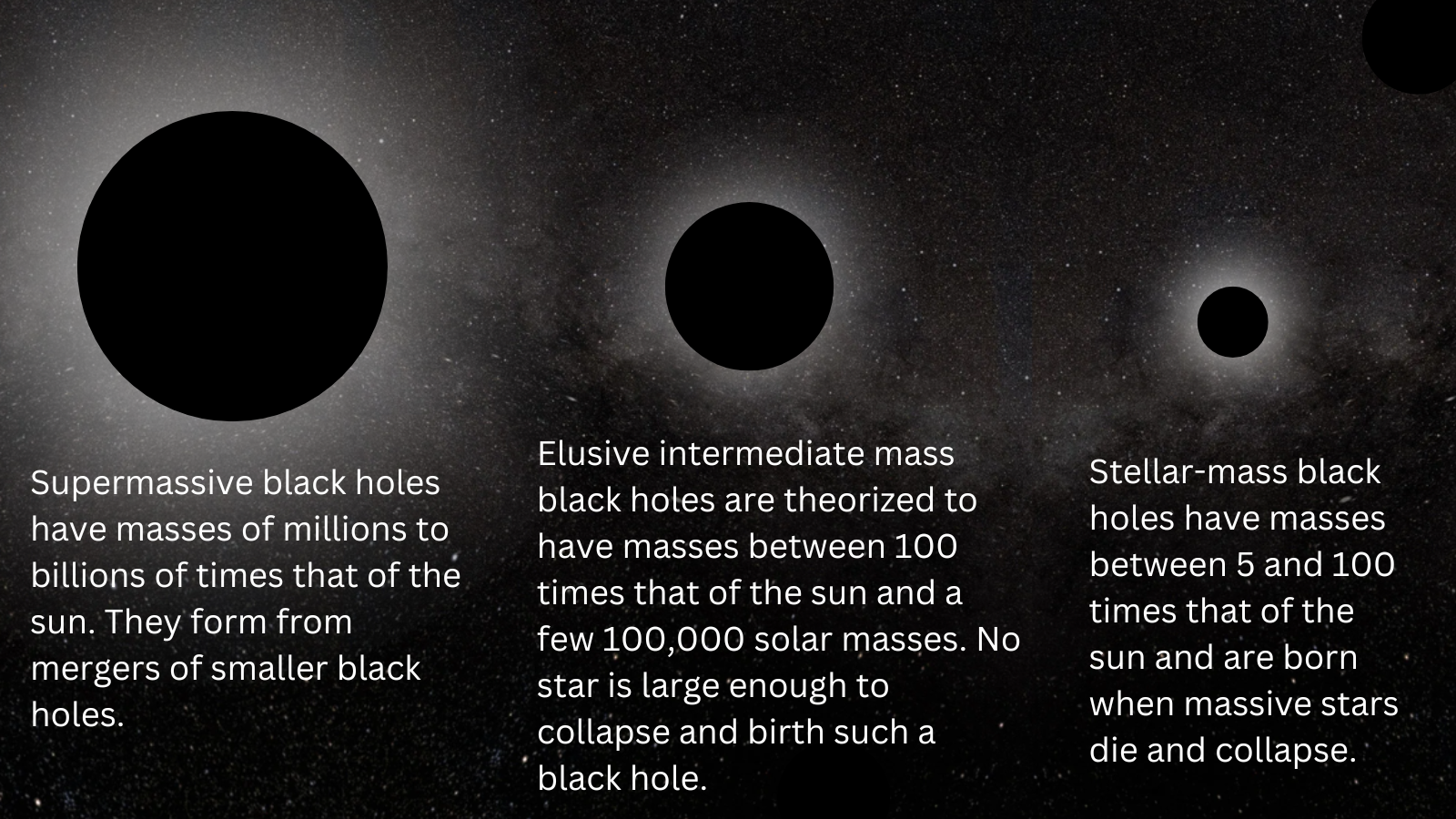

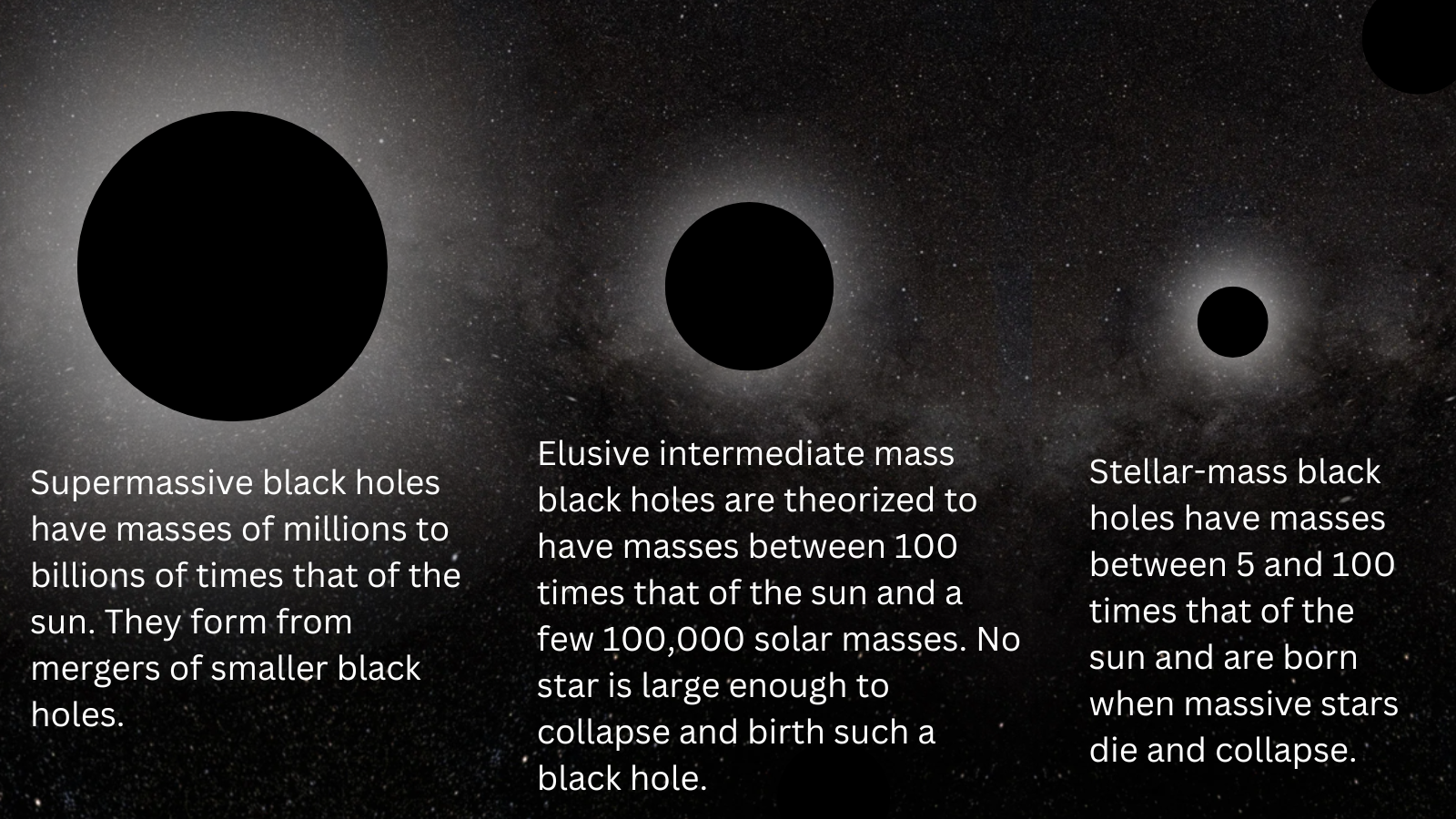

Supermassive black holes are thought to have masses millions or billions of times that of the sun, while stellar mass black holes, which form from dying massive stars, are thought to have masses from three to many hundreds of times the mass of the sun. That leaves a huge mass range between these two types of black holes in which the aptly named intermediate mass black holes are thought to sit.

Because supermassive black holes are thought to grow via merger chains between increasingly massive black holes, it is reasonable to presume that intermediate mass black holes play a key role in this growth process. That means black holes in this mass range should be fairly ubiquitous in the cosmos, yet astronomers have had a really tough time discovering them.

“I think it’s really difficult to overstate how bad we are at finding intermediate mass black holes. We are excellent at finding supermassive black holes, and thanks to LIGO-Virgo-Kagra gravitational wave detectors, we are getting better at finding stellar mass black holes, but I could count on my hands the number of intermediate mass black hole candidates that have reached some kind of consensus within the astronomical community,” Dage said. “Up to this point, TDEs from intermediate black holes are known to exist, but are very difficult to observe. They are most of the time overshadowed by other activities within the galaxy’s central region.”

Astronomers can distinguish between TDEs caused by intermediate black holes and those generated when supermassive black holes rip up stars due to the location they occur and the duration of these events.

“With our current understanding of TDE behavior, we know that event duration scales as black hole mass, so all other things being equal, shorter timescale points to lower mass black holes,” Dage said. “What sold me on AT2022zod being special was when I compared it to other TDEs at similar distances or with similar host galaxies, and it didn’t fit in with the same behavior.”

The discovery of this off-center TDE could also reveal more about the environment occupied by this intermediate-mass black hole. For instance, it is pretty evident that TDEs are much more likely to occur in regions in which stars are densely packed together. “If you’re not in some kind of star cluster, generally the host galaxy’s central nuclear star cluster, then you’re just not going to have a TDE, because the odds of a given star waltzing in near the black hole are too low,” Dage said. This stellar density is found at the heart of galaxies, but there are also non-central regions of galaxies in which stars are also jammed together tightly.

Failed supermassive black holes?

The team theorizes that this TDE occurred in a globular cluster or an ultracompact dwarf galaxy (UCD) within SDSS J105602.80+561214.7 itself. Both globular clusters and UCDs are densely packed conglomerations of ancient stars reaching the end of their lives.

“These systems are basically black hole factories, and their crowded and dynamical systems provide opportunities for black holes to merge and grow into the intermediate mass range, particularly through runaway stellar collisions,” Dage said. “When you combine this with the observational evidence for kinematic studies of black holes in UCDs, it makes them very compelling environments to host intermediate mass black holes!”

The origins of UCDs are currently shrouded in mystery. These dense stellar regions could arise when two globular clusters are drawn together, collide and merge, or UCDs may be dwarf galaxies that have been stripped of their outer stars, leaving them as a compact and dense stripped galactic nucleus.

“These two different formation scenarios have very different implications for the black hole evolution. If they are stripped nuclei, then they are ‘failed’ supermassive black holes, with a similar formation pathway to the supermassive black holes and large galaxies,” Dage explained. “If they’re just big globular clusters, then things could be completely different, and dynamics play a vital role in black hole formation and evolution.”

Dage said scientists know elliptical galaxies host both globular cluster stellar systems and UCDs, but in this case, the host galaxy is so far away that the team can’t quite disentangle the nature of the actual environment of AT2022zod. “We just know it’s in some kind of star cluster,” Dage said. “I personally would love it if it were in a globular cluster, but from what we know of more nearby systems, a UCD makes a lot of sense as a host in the nearby universe.”

She added that many studies of the physics of UCDs show they host black holes in the mass range estimated for AT2022zod. This includes a system in the Milky Way called Omega Centauri, although Dage pointed out there is still some debate about whether this densely packed star cluster in our galaxy is a UCD or a globular cluster.

While the environment of the TDE AT2022zod may remain a mystery for the foreseeable future, the team’s research could provide a much-needed roadmap for discovering intermediate black holes, which will become especially relevant when the Vera C. Rubin Observatory begins conducting its decade-long Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

“Rubin is poised to make such a huge impact — it will provide incredibly sensitive 10-year optical coverage of millions of star clusters within 330 million light-years, and ought to be sensitive to populations of TDEs hosted by dense stellar environments,” Dage concluded. “We just need to make sure we are looking in the right places, can do prompt follow-up to better understand the physics and the host system, and be able to interpret what we see.”

The team’s results are available on the paper repository site arXiv.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly