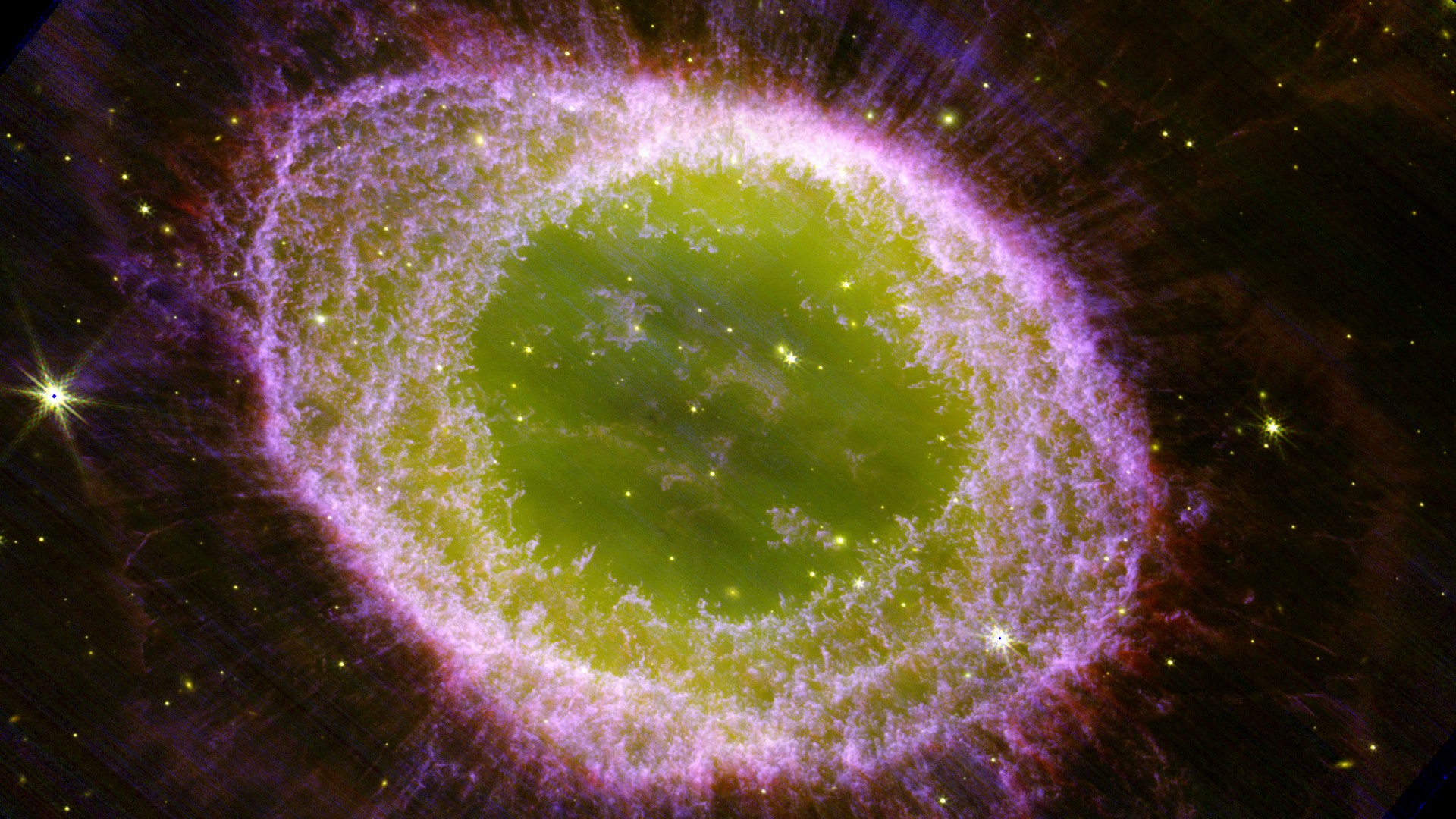

I would suppose that just about any good book on astronomy would contain a photograph of what might best be described as the “smoke ring” of the sky. Others might call it a doughnut or a cosmic bagel, but the popular name for this object is simply the Ring Nebula, located in the constellation of Lyra, the Lyre. Although generally considered a summer constellation, Lyra, it is still very well placed for viewing, now more than two weeks into the autumn season.

Head outside this week at around 10 p.m. local daylight time and face due east. Approximately two-thirds of the way up from the horizon, you’ll spot a brilliant bluish-white star. This is Vega, the brightest star in Lyra. The only other star at that hour that outranks Vega in brightness is yellow-orange Arcturus in the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman. But Arcturus will be at the opposite part of the sky, about halfway up in the southwest.

The constellation of Lyra was supposed to represent Apollo’s harp. Six fainter stars form a little geometric pattern of a parallelogram attached at its northern corner to an equal-sided triangle. Vega gleams at the western part of the triangle. The two lowest stars in the parallelogram are Beta and Gamma Lyrae. Beta is sometimes also known as Sheliak and Gamma also goes by the name of Sulafat. Between these two stars, but a trifle nearer to Sulafat is where you will find the Ring Nebula.

Want to see Ring Nebula or other nebulas for yourself? Be sure to check out our guides for the best binoculars and the best telescopes.

And if you’re interested in dabbling in your own impressive skywatching photography, don’t miss our guide on how to shoot the night sky. We also have recommendations for the best cameras for astrophotography and the best lenses for astrophotography.

A celestial curiosity

Antoine Darquier de Pellepoix of Toulouse, France first saw the Ring Nebula in January 1779. Using a telescope of about 3-inch aperture, he described it as a perfectly outlined disk as large as Jupiter, but dull in light and looking like a fading planet.

A short time later, Charles Messier also saw it and added it to his catalog of comet masqueraders listing it as Messier 57, or M57. But like de Pellepoix, Messier’s telescope was too crude to give a true picture of what he was looking at. “It appears composed of very small stars,” Messier wrote, adding that, “but with the best telescope it is impossible to distinguish them; they are merely suspected.”

Not until six years later, in 1785, did Sir William Herschel (the discoverer of Uranus) actually see M57 as a ring. “It is among the curiosities of the heavens; a nebula that has a regular concentric dark spot in the middle.” Herschel, however, incorrectly assumed that he was looking at “a ring of stars.”

Gas shell or tunnel?

As for the true nature of the ring, it is generally believed that sometime in the distant past, a star nearing the end of its life and having used up all of its nuclear fuel hurled great masses of gas out into space in a gaseous shell. This surrounding gas is still expanding and is made visible by the illumination from its extremely hot central star (which is merely the core left from the original star). The surface temperature of the star has been estimated at 216,000º F (120,000º C). Our own sun is expected to undergo a similar process in a few billion years.

The Ring Nebula is the most famous and among the brightest examples of what astronomers refer to as “planetary” nebulas. But despite their name, planetary nebulas have absolutely nothing to do with planets. It is simply because that generally they appear in telescopes not as stellar point sources, but as small diffuse disks.

For a long time, the explanation for the Ring Nebula’s appearance was that the hazy disk was so much brighter around its edges that it looked like a ring; that we are looking through the rim of the gaseous shell lengthwise. Therefore, there is much more gas in our line of sight and the refraction of the light from the central star makes it more luminous, because each particle acts as a prism or mirror, and reflects the rays back to us.

More recent research, however, has confirmed that it indeed is likely a ring, or torus of bright material surrounding its central star. In fact, based on photographs taken from Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona, some think that we might actually be looking down at a tunnel of gas shaped like a barrel or cylinder.

See it for yourself

As to actually viewing the ring for yourself, it shines at magnitude +8.8, and thus is far too faint to be seen with the unaided eye. Any good pair of binoculars will locate it, though it will look almost star-like in appearance because of its small apparent diameter. The ring shape might just begin to become evident to most eyes in small telescopes using a magnification of 100-power, although at least a 6-inch telescope is recommended to see the ring clearly. With larger instruments and higher magnifications, the ring appears distinctly as a “tiny ghostly doughnut.”

You might ask if the central star is visible within the “doughnut hole.” The answer is “yes and no.” The magnitude of this star is roughly +15. That means, it’s almost 4,000 times fainter than the faintest star that you could see with your eyes without any optical aid. And don’t bother to look for the central star unless you have a telescope of at least 12-inch aperture. Even then, you will need an absolutely dark and clear, pristine night to get a chance at even a brief glimpse at it.

Only once, nearly half a century ago, in 1975, did I see it. It was at the annual midsummer Stellafane convention, just outside of Springfield, Vermont. The Ring Nebula was one of the objects in view through the 12-inch Porter turret telescope atop Breezy Hill. I hasten to add however, that my eyes were much younger back then, and the overall level of light pollution over much of New England was considerably less back then as compared to now.

Bottom line: certainly, you should have no problem in sighting the Ring Nebula, but its central star quite likely may stay out of your reach.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.